|

Model engines that were just being released for production

in the year this article was written are now 52 years old, and would therefore now qualify as vintage

engines in any modern model engine museum. The article's author, Pete Chinn, probably did not even conceive

of the possibility while writing his piece in November 1959. He has some enviable model engines from

as far back as the Stagner 7.4 cu.in. V-4, circa 1909. At the time, the Wright Brothers were developing

engines not a lot larger than that for their full-size craft (well, a tad bit larger). That makes model

aircraft engines, as an entity, just about 100 years old. Amazing. Sure, there are a few out there older,

but not many. The December 1959

edition of American Modeler had a follow-on article with more of Mr. Chinn's model motors. As P.G.F. "Pete" Chinn points out, collectors who really know their power plants start

Model Motor Museums

In the quarter century since the beginning of commercial model engine manufacture in the United States,

the minia-ture internal combustion motor has been brought to a stage of development where its comparable

performance can, and often does, exceed that of almost any full-size i.c. engine.

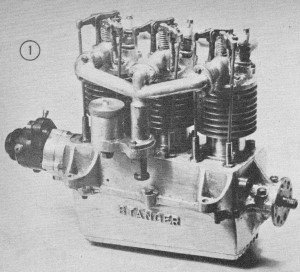

(1) Post-World

War One Stanger 3 cylinder inline o.h.v.

(2) 50-year-old

Stanger 7.4 cu. in. V-4

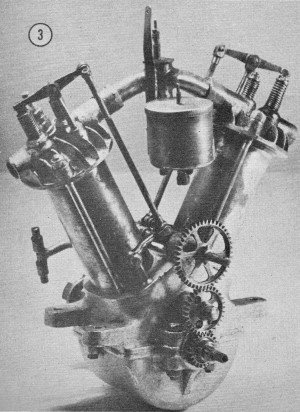

(3) 3.7 cu.

in. 4-cycle V-Twin used by Stanger in 1914 to set 51 second duration record

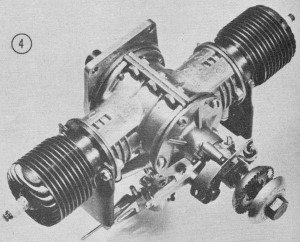

(4) Herkimer

"OK" Twin marketed in 1939, reintroduced after WW-II displaced 1.2 cu. in., weighed 24 oz,. turned 16

to 20" prop

(5) Gwin-Aero;

(6) Ohlsson 23; (7) Airstream Dennymite ... last trio popular engines of 1938-39

(8) Post-war

"OK" Super-60 with shaft valve and rear timer assembly; (9) Super-Cyclone; (10) 1940 May Silver-King

which reappeared in 1946 as the Rocket-4S

(11) Ohlsson

Gold Seal-.55; (12) G.H.Q.-.52; (13) Brown Junior

In twenty-five years, we have seen horsepower per cubic inch go up .to four, six, or even eight times

its original level. Horsepower peaking speeds have trebled. Today, it is possible to pick up a text-book

on full-scale engine design and find the author quoting model engine performance statistics alongside

those for aircraft and racing automobile engines. In 1939, successful manufacturers counted

their annual production in thousands. Today, leading producers think in terms of hundreds of thousands.

The total number of different types of model motors that have been built all over the world, excluding

purely amateur efforts, is certainly not far short of four figures and includes an infinite variety

of designs. In short, the history of the miniature gas engine is a fascinating story, well worth

recording. What could be a better way of doing this than to preserve examples of model engines, old

and new, tracing development from the earliest times to the present day? Just such an activity

is now going on and, during the past five years, there has been a marked increase in serious engine

collecting. Much of this is due to the enthusiasm of Bruce Underwood of Columbus, Ohio, who began collecting

early and unusual type model engines several years ago. He went about this. thoroughly, even having

printed special letterheads, "Underwood Model Engine Collection." The writer was called in at

an early date to help establish the identity and date of a few of these engines and, subsequently, became

one of the original members of Underwood's collector's group, which now includes eighteen people owning

a grand total nearing two thousand model engines of all sizes, types and nationalities. Individual collections

vary in size, but average out at close to the 100 mark. Six members, Bruce Underwood, Steve Ditta of

Queens, N. Y., Don Belote of Toledo, Ohio, Douglas Wendt of Whitefish, Montana, Joe Wagner of San Fernando,

Calif., and the writer, have collections of over 200. The group has special forms for listing engines

and there is a system of coding to establish the condition of each engine, whether it is original in

all respects, etc. Some enthusiasts collect all kinds of model motors; others specialize by

concentrating on certain types or models of a certain era. Some try to assemble engines from as many

different countries as possible. Here it may be remarked that at least two dozen nations are known to

have produced model engines. Quite a bit of international correspondence is going on between American

collectors and enthusiasts in other lands, in search of rare foreign engines. It is not unknown, either,

for rare American engines to come back home after a twenty year exile in another country. Engines

don't necessarily have to be antiques or foreign-made to be worth collecting, however. For example,

the period 1945-50 was, we think, the golden era of American model motors and a collection including

such notable contri-butions to design progress as the Anderson Spitfire, Arden 099, Atwood Champion,

Dooling 61, Elf Four, Forster 29, McCoy 60, O.K. Twin and many others, would, alone, be well worth assembling.

One English collector, Mike Beach, is, in fact, concentrating on U.S. spark-ignition engines of these

truly vintage years. Although the hobby of building and flying gas engined model planes did

not really begin until the advent of the Brown Junior engine in 1934, a number of gas engines for model

planes did, in fact, exist long before this. In 1908, David Stanger, an English automobile engineer,

designed and built a four-cylinder Vee-type engine, that was one of the very first gas motors to be

used in a model plane and is, we believe, the oldest model aircraft engine still in existence. This

engine, which was recently donated to the writer's collection by Alfred Stanger, son of the designer,

is of the four-cycle type with pushrod operated overhead exhaust valves and automatic inlet valves.

The crankshaft is built-up in two sections, bolted to-gether at the center and runs in two bronze bushings

in a cast aluminum crankcase. Cast-iron pistons, each with two rings, are used and the cylinders have

no cooling fins, although the cast-iron cylinder-heads are finned. No midget, the engine has a bore

and stroke of 134 x 1 "h inches for a total displacement of 7.36 cu. in. and weighs 86 ounces, less

ignition gear but including a small brass gas tank mounted above the float-valve carburetor.

In 1910, David Stanger had this engine, which was rated at 1.25 hp at 1,300 rpm, fitted to an 8-foot

biplane weighing 21 lb. According to contemporary reports, the model flew successfully for short durations.

Later he used the same engine, driving a 30/22 prop at 1,600 rpm, to power a 10-foot monoplane weighing

20 lb. In April 1914, Stanger set the first official record by a gas engined model plane,

with a flight, before Royal Aero Club observers, of 51 seconds - a mark that was to stand for 18 years!

For this record, he used the Vee-Twin engine illustrated. This is of similar design to the Vee-Four,

but has a stiffer, one-piece crankshaft with connecting-rods in-corporating split lower eyes. Due to

the engine's smaller displacement and lighter weight (42 oz.), Stanger was able to build a smaller and

lighter aircraft for it. The model, a canard biplane, had a span of 7 ft. and weighed 10¾ lb. The engine

drove a 22/18 prop at 2,000 rpm. Before World War I, the number of model builders who

had flown a gas engine successfully could probably be counted on the fingers of one hand. One of them

was Ray Arden, later to become famous for his Atom and Arden motors. But at least three attempts had,

nevertheless, been made to market i.c. engines for model aircraft. These engines, however, seem to have

suffered from excessive weight and limited power and, after the promising start made by the pioneering

amateurs, nearly twenty years passed before any real progress was made. During this time,

model gas engine design and construction had not been at a standstill because many types of relatively

small engines, both four-cycle and two-cycle, had been developed for model power boats. So it was that

an American Wall 1.6 cu. in. two-cycle marine engine powered the British model that, in 1932, broke

Stanger's 1914 record, while, in America, Bill Atwood was developing his Baby Cyclone by building and

operating speedboat motors. Then, of course, there came Bill Brown, Maxwell Bassett and

the Brown Junior motor - the never-to-be-forgotten Brown Junior that really put gas modeling on the

map. Making its first appearance in 1932, the Brown went into series production in 1934 and became the

true progenitor of the model airplane motor as we know it today. No historical collection of

model motors can possibly be complete without a Brown Junior. The Brown is not famous merely because

it was the first of its kind. It was much more than this. It was essentially "right" from the beginning

and remained practically unaltered in its six years of production. Despite the rapid introduction of

numerous other makes, the Brown succeeded in remaining the No.1 choice for thousands of knowledgeable

modelers for quite some time. One has only to look through Frank Zaic's Yearbooks of 1937-38 or contemporary

magazines, to see that gas model designers of the day more often specified the Brown than all other

similar sized motors added together. That famous Bill Stout adage "simplicate and add lightness"

could well have been in Bill Brown's mind when he de-signed the Brown Junior. Let's take a look at it.

The engine contains a minimum of separate parts; two screw threads-cylinder-to-crankcase and

crankcase back-plate-serve to unite the complete engine. A one-piece steel cylinder with integral head,

integral fins and welded bypass and intake tube, are used. The crankcase is neatly diecast in aluminum-silicon

alloy and carries a bronze main bearing. The simple and effective ignition timer features an eccentric

bush mounting to facilitate points gap adjustment. The complete engine, less coil, condenser and gas

tank, weighs but 7½ oz. It has a bore and stroke of 7/8" x 1", giving a displacement of .60 cu. in.

Some of the parts of the Brown, its slender 5/16" dia. crankshaft and tiny wristpin, look feeble

beside the massive components of today's high-output engines, but, in the thirties, these were quite

adequate for the power then required. Most engines of around .60 displacement were, at that time, rated

at 1/5-hp. Such an output was available on the 14" and 15" dia. props then in use. A couple of years

ago, however, we put our Brown through a full dynamometer test to determine torque and brake horse-power.

The nominal rating of .2 bhp came up at just over 4,000 rpm and a maximum output of just. under .26

bhp was obtained at 6,200 rpm. Additional material by Mr. Chinn on Model Motor Museums will

appear in the next issue.

Articles About Engines and Motors for Model Airplanes, Boats, and Cars:

|