|

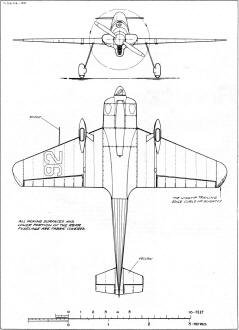

Website visitor Gareth P. wrote

to request that I scan and post the article for Falck's Special "Rivets" racer for

Formula I events. The article is a documentary on the airplane and its designer

/ builder / owner, Bill Falck. As such, it does not include plans for building a

model; however, it does include one of uber draftsman Björn Karlström's 4-views

that could be used for creating a set of plans. BTW, the AMA plans service has 5

version of Rivets building plans

if you want to go the easy route.

Rivets

The plane to beat in Formula I Races is Bill Falck's 'Special.' Sixteen wins

- 20 firsts and seconds since 1964!

by Don Berliner

Bill Falck's Rivets.

"Rivets" is almost as fast as the GeeBee! And a lot more streamlined! In its

day, the glamorous GeeBee Super Sportster was speed personified. If it was running

right, nothing could keep up with it. It is easily the most famous American racing

airplane of all time. Yet it was crude and clumsy compared with "Rivets."

The strange-looking Falck Special No. 92 has been clocked twice at 231 mph around

a three mile course, even though it has a little 201 cu. in. engine normally rated

at 100 hp and certainly producing less than 150 hp. The great GeeBee, in its prime,

was clocked at 253 mph around a much faster five mile course - pulled by a huge

1340 cu. in. engine which developed at least 800 hp.

How has Rivets designer/builder/owner/ pilot Bill Falck done it? He has combined

post-GeeBee engineering with two decades of personal experience and a lot of extremely

hard work. His racer has the least frontal area of any machine in its class. Takeoff

acceleration has been sacrificed for maximum speed on the straightaway. He has accepted

the poor flying qualities of a steeply swept-back wing for the extra visibility

which enables him to see the pylons while flying higher than anyone else, and thus

staying out of traffic.

Bill Falck's Rivets, side view.

As important as absolute speed is in air racing, consistency is even more so.

What good is a super-fast airplane if mechanical problems keep it on the ground

most of the time? The classic GeeBees (R-1 and R-2) won but a single Thompson Trophy

Race between them, despite their speed. Rivets, on the other hand, has won no fewer

than 16 Formula I races. At one time, Bill Falck had an unprecedented string of

eight straight wins. In the 23 races they have flown since the sport came back in

1964, they have placed first or second in 20!

With the Formula I class being the most competitive of all during its 24 years,

such a record of success is all the more surprising. Some of the finest pilots who

ever flew the pylons have tried to dislodge Falck and his model from their place

in victory lane, but no one has been able to do it consistently. "Shoestring" pilot

Ray Cote has come the closest, beating them at Reno in 1968-69-70, but Cote works

all year long for that one race, while Falck is there every time the flag is dropped

for a Formula I race.

These winning ways didn't come quickly or easily. There were slow and unhappy

days, for Bill Falck knew no shortcuts to victory. When he first brought Rivets

out in public for a race many laughed, for it was a funny-looking airplane. The

bulging canopy extended all the way to the spinner, and the airplane flew around

the pylons with its nose in the air. Bill had built his racer so he could fly it

while lying flat on his back, but this streamlining idea was declared unsafe shortly

before his first race in No. 92, and the hurried modifications weren't quite right.

He still placed second in the Consolation Race, though his speed was only 142.5

mph.

Rivets underwent the first of several major changes which were destined to turn

an also-ran into a winner for the following year - 1949. As operator of the small

Warwick Airport in New York, Falck had a lot of time on his hands when snow made

his dirt runway useless, so he put the time to good use by methodically re-working

his airplane, piece by piece. The first area to get a good going over was the canopy,

and the original "plastic bathtub" was replaced by a clean canopy made from pieces

of Aeronca Champion windshield. Months of hard work paid off to the tune of 20 mph

and first place in the Consolation Race at Cleveland.

Yet Falck and his Rivets were a full 15 mph behind the winners, and so few people

paid attention to them, except in the pits where "Willie" was becoming recognized

as a very competent student of racing. But they were no particular threat to people

like Steve Wittman and Bill Brennand and John Paul Jones, who were doing the winning

in those days.

In the time between the last of the old Cleveland Races in 1949, and the 1951

Detroit meet, Falck completed the single most important modification to his racer

- the change that was soon to make it winner. He designed, built and proved the

complicated set of plumbing under the sleek new cowl that gave the model a sound

like it had several extra cylinders. Basically, it was an updraft cooling system

with tuned exhaust pipes, all exiting through an augmenter in the tunnel underneath

the cowl. Far more efficient than the usual, simple exhaust pipes and cooling-air

outlet, it enabled Rivets to advance from consolation to final races. This happened

first at Miami in 1950, when they placed 7th at 173 mph, and soon became a matter

of habit.

Specifications:

Dimensions: Length - 18' 0" Wingspan - 17' 9" Wing

Area - 66 sq. ft. Wing Airfoil - modified M6 Aspect Ratio - 5.23-1 Empty

Weight - 635 Ibs. Normal Loaded Weight- 855 lbs.

Performance: Maximum Speed (est.) - 255 mph. Landing

speed - 70 mph Cruising Speed - n.a. , Cruising Range - n.a.

(n.a. - not applicable, as the airplane is never flown

cross-country.)

Getting into the finals was a step in the right direction, but hardly the same as

winning. Falck's first win was a dramatic one, and set the theme for many races

to come. At a small race in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in the spring of 1952, Bill

qualified second following the great Wittman and then shared preliminary heat wins

with him. In the 12-lap finals, Wittman got off to his usual fast start and Falck

to his usual slow start. Lap by lap, Rivets gained on the famous Bonzo, until it

was clear to everyone that only time or luck could keep that upstart with the funny

airplane from pulling the upset of the year. For Wittman, there was too much time

and no luck, as Falck passed him on high with a couple of laps to go and won by

the narrow margin of 186.95 mph to 186.79 mph. A winter spent hammering out a fancy

set of new wheel pants was time well spent for Bill Falck.

Racing soon slipped to the level where it was little more than a friendly game

played by Easterners at such places as Niagara Falls, Oshkosh and Ft. Wayne. Of

11 such races held from 1954 through 1960, Falck and his racer won five, were second

in three, and third in two - by far the best overall record of the period. Moreover,

they hung up their first really important record by qualifying at Niagara Falls

in 1956 at 208.81 mph, five mph better than the old mark. It was all a little sad

though, for the great performances were before small crowds and received almost

no publicity. Even the great story of Rivets being reduced almost to ashes by a

fire in 1956 and then coming back to win the big race of the next season went almost

unnoticed.

When racing came back at Reno in 1964, Bill Falck was not exactly an instant

hero. He didn't even fly in that first race, but he won a photo finish with Bob

Downey at St. Petersburg, Florida the following winter. In 1965's big races, his

best were seconds at Reno and Las Vegas. He then repeated his win at St. Pete in

1966 and charged off on the greatest winning spree the sport has ever seen. Victories

at Frederick, Maryland and Reno gave him the first Formula I National Point Championship.

Winning all three races in 1967 gave him a second championship. In 1968, two firsts

and a second meant yet a third championship. In 1969, it was three firsts and a

second, and championship number four. They combined wins at Ft. Lauderdale, Florida,

and Wilson, North Carolina, and a second at Reno for a fifth straight national title

in 1970, along with a qualifying record of 231.26 mph.

As the 1970's dawned and the ranks of Formula I began to swell with more new

racers than had ever been seen before, there were increasing chances that new airplanes

would come along to take the place so long held by Rivets. Its excessive weight

- 635 lbs. vs. 520-550 lbs. for most of the other fast ones - was a serious handicap.

Being more than 20 years older than when he built No. 92, Falck seemed unwilling

to start over on a new racer, though it was widely recognized that he had the skill

and knowledge to build a new airplane that would be as unbeatable as Rivets had

been for the past decade.

But, until someone can consistently beat him at more than one race site, Bill

Falck will no doubt continue to terrorize Formula I with possibly the finest racing

airplane, pound for pound, that has ever flown.

Note: Our special thanks to Eddie Fisher, of Birdland Airport, Leroy, Ohio for

suggesting this airplane.

Rivets 4-View, Sheet 1

<click for larger version>

Rivets 4-View, Sheet 2

<click for larger version>

Björn Karlström Drawings:

Posted October 9, 2012

|