|

Website visitor Stephen B. just

wrote asking me to post this article for the Folkerts SK-3 Speed King. As the designation

suggests, there were two prior iterations of the airplane. The Folkerts was a paradigm

breaker in its day (circa 1930s) for using an inline engine rather than a radial.

The story mentions that even "today" (...being 1973) the battle of opinions continues.

Guess what? In 2012, there is still no agreement - take a look at the variety of

racers at Reno. Although there are no construction plans, the inestimably talented

Björn Karlström provided a detailed 5-view of the airplane.

Folkerts SK-3 Speed King

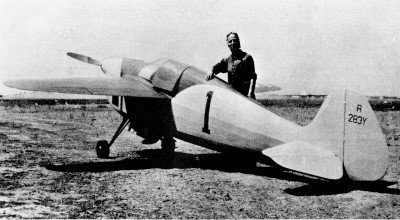

Racing great, Harold Neumann, and the Folkerts Special "Toots." Small even when

compared with a Formula One racer, this powerful machine demanded the finest of

piloting skill.

Don Berliner

This early Folkerts exemplified its designer's

concept - minimum airplane with the biggest engine that fitted and careful attention

to streamlining.

| Specifications of the SK-3 Dimensions: Length-21 '0"

Wingspan-16'8" Wing Area-51 sq. ft. Height-4'0" |

Empty Weight-840 lb. Gross Weight-1385 lb. Performance: Top

Speed-over 275 mph |

For almost as long as there has been air racing, there has been a battle between

radial and in-line engines. The prettiest, sleekest machines have packed straight

or V engines into their graceful cowlings ... but most of the big winners have carried

bulky, round engines up front. No doubt about it, an in-line engine is a

lot easier to cowl in, and the result is a much cleaner and faster airplane. if

the comparable radial engine has about the same power, and that's the catch. Engine

manufacturers have long made far bigger and far more powerful radial engines than

they have in-lines. And as any racing person knows, you can't beat cubic inches!

It was true back in the 1930s, when the fat Gee Bee was faster than any

of its slimmer rivals. And it's just as true today, when you pit Bearcats and Sea

Furys against the slender-but-less-potent Mustangs and Cobras. What chance does

a 1650 cu. in. Rolls Royce V-12 have against a 2800 cu. in. Pratt & Whitney?

Attempts to even the odds have usually resulted in V-12s so souped-up that they

won't hold together long enough to finish, let alone win. It was equally

as one-sided back in the Golden 30s, when eight of the ten pre-World War II Thompson

Trophy Races were won by Pratt & Whitney-powered airplanes. Of the other two,

one was a French government-sponsored airplane that simply "out-monied" everyone

else. And the other was a slick little Menasco straight-six job with 1/3 the cubic

inches of the next three racers that followed it across the finish line. And no

more than half the horsepower.

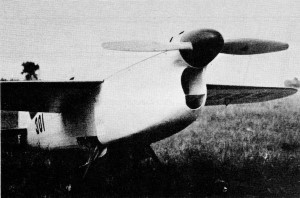

By 1937, Folkerts was up to 400 hp. Had

three times the power of today's Formula One with 3/4 the area.

Competition more than doubled its displacement.

The six-cylinder Menasco Super Buccaneer was shoe-horned into this tight cowling,

in Thompson winner.

How can it be done with such a handicap? Well, for one thing, a sharp engineer can

create a much cleaner, smaller airplane behind a slim in-line engine, and any designer

knows the shortest route to speed is streamlining, not power. So, while a powerful

streamlined airplane is better than an underpowered streamlined airplane, the edge

goes to streamlining. At least that was the way Clayton Folkerts saw it.

Build an airplane as small as possible and give it the biggest engine that will

fit. And if you do it right, you should win a few races. For Folkerts, of Bettendorf,

Iowa, and later Lemont, Illinois, it started in 1930 with the Mono-Special, later

called the Folkerts SK-1 Speed King. Powered by a four-cylinder, in-line 310 cu.

in. American Cirrus engine rated at 90 hp, it was a strut-braced mid-wing with rather

crude landing gear. Careful work brought its speed up from 142 mph at Chicago in

1930 to 187 mph at Cleveland in 1935, though by then it was called the Fordon-Neumann

Special and was being flown by Harold Neumann. It raced until 1937 as the Whittenbeck

Special and then simply vanished. But Clayton Folkerts didn't. His second

racer appeared in 1936 and was a major improvement over the first. The SK-2 "Toots"

firmly established his concept of a racing airplane: Minimum wings (50 sq. ft.,

compared with 66 sq. ft. required of today's Formula One racers), maximum power

(supercharged 363 cu. in. Menasco C4S Pirate four-cylinder, rated at 185 hp), and

one of the earliest, simplest retractable landing gears. With 1935 Thompson winner

Neumann at the controls, the tiny SK-2 outran several more powerful rivals to place

fourth in the 1936 Thompson at 233 mph. Roger Don Rae got its speed up to 243 mph

in 1937, and the airplane ended its brief career when Gus Gotch crashed in it at

Oakland in 1938. With his theories pretty well proven, Clayton Folkerts

moved ahead. His 1937 racer was simply more of the same: A few inches more length

and wingspan, considerably greater weight ... and lots more power. The little Menasco

was replaced by its big brother, a six-cylinder, 489 cu. in. C6S-4 "Super Buccaneer"

souped-up to deliver some 400 hp at 3300 rpm. It had three times the power of a

Formula One, yet only 3/4 the wing area. This had to spell "performance," but it

could also spell "trouble."

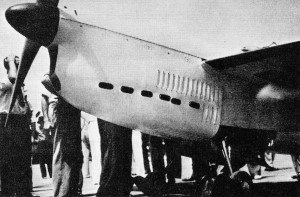

Simple retractable gear was a masterpiece

of engineering.

But Folkerts knew enough about designing an airplane to keep it within reasonable

handling characteristics. In fact, the pilot chosen to handle the new baby, Rudy

Kling, had fewer than 200 flying hours when he sat on the starting line for the

Greve Trophy Race at Cleveland, on Sunday, September 5, 1937. Lined up alongside

Kling were six other Menasco-powered airplanes, in what must have been one of the

classiest collections of racers ever seen. And at the end of ten laps of the ten-mile

race course, they were almost as closely bunched as they had been at the start:

Kling beat out Steve Wittman by 1.9 sec. and Gus Gotch by 4.5 sec., as they

averaged 232.27 mph, 231.99 mph and 231.59 mph, respectively. In competition

with the best small racers in the world, Folkerts and Kling had proven that their

team was a most effective one. But the big test was yet to come. Prior to the Thompson

Trophy Race, Kling entered the SK-3 "Pride of Lemont" in a qualifying race against

Wittman in his big Curtiss-powered "Bonzo," Roscoe Turner in the Laird-Turner "Meteor,"

a Ray Moore in a Seversky military prototype. Giving away 600-1300 cu. in., Kling

was not expected to do very well, and he placed third at 240 mph, behind Wittman's

259.1 mph and Turner's 258.9 mph. But he was less than a minute back at the finish

of the 50-mile race, and began looking forward to the Thompson with growing enthusiasm.

That race was for 20 laps of the ten-mile course: 45 minutes of hard, fast,

on-the-deck flying. With insufficient power and insufficient experience the Folkerts-Kling

combination was seen as a dark horse, at best, because they were pitted against

the best in the business -- Wittman, Turner, Earl Ortman and others. At

the takeoff, Kling's heavily loaded little airplane found itself in eighth place

in a nine-plane field. By lap five, however, he had moved up to fifth place and

was in striking range of the leaders, if only a few of them would slow down a bit,

please! At the start of lap 15, he started to make his move, and quickly advanced

to fourth, behind Wittman, Turner and Ortman. On lap 17, Wittman ran into engine

trouble and had to pull back on the power, moving everyone up a notch. Then, on

the final lap, another piece of good fortune, as Turner swung around to circle a

pylon he thought he had cut, and let Ortman and Kling go by. As Ortman in

the big Marcoux-Bromberg, and Kling in the Folkerts, roared toward the finish line,

Rudy Kling took advantage of his excess altitude and dove to gain speed. He passed

Ortman as they approached the wire, and crossed it a mere 50 feet in the lead. His

margin was but .57 seconds, as he averaged 256.910 mph to Ortman's 256.858 mph,

in what is still the closest finish of any "unlimited" air race in history.

The joy in the Folkerts camp was as great as befits a long-shot victory. They

had taken on all the horsepower that American air racing could muster, and they

had won. And they had even topped the speed record set by the great Jimmy Doolittle

in his immortal Gee-Bee. All this was only 489 cu. in. and 400 hp. Indeed, it was

a great day for the little guy. But it was the last great day for a Folkerts

racer. At Miami, a few months later, Kling was rounding the first pylon of a race

when a violent gust of wind caught the SK-3 and flipped it into the ground. Neither

survived. In 1938, the fourth and final Folkerts appeared at Cleveland - the SK-4.

It didn't race that year because of wing flutter, but returned the next year and

crashed on a qualifying flight. And so it was over, this tale of the Folkerts

racers. They had won and they had lost. They had lived and they had died. And what

remains is the knowledge that on one glorious day, David had again beaten Goliath.

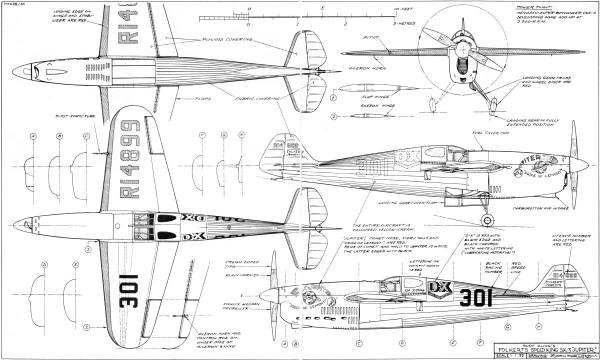

5-View

of Folkerts Speed King SK-3 (by

Björn Karlström)

<click

for larger version>

Notice:

The AMA Plans Service offers a

full-size version of many of the plans show here at a very reasonable cost. They

will scale the plans any size for you. It is always best to buy printed plans because

my scanner versions often have distortions that can cause parts to fit poorly. Purchasing

plans also help to support the operation of the

Academy of Model Aeronautics - the #1

advocate for model aviation throughout the world. If the AMA no longer has this

plan on file, I will be glad to send you my higher resolution version.

Try my Scale Calculator for

Model Airplane Plans.

A couple different version of the

Folkerts Speed King are available

from the AMA Plans Service (pages 40 & 41).

Björn Karlström Drawings:

Posted September 18, 2012

|