|

Balsa wood was a special thing to me as a kid. To me, it represented the essence

of model airplanes and model rockets. At the time - the 1960s and 70s - plastic

and foam as model components were considered a sign of cheapness, low quality, amateurishness.

It was like having "Made in Japan" stamped on it. Now, of course, it's a different

world where Japan is renowned for some of the highest quality electronics and cars

and the plastic and foam ARFs represent some of the highest-performing aircraft

at the flying field. I have owned a few of those foamies, but still, at least for

my tastes, nothing beats the look, feel and aroma of balsa. Somehow the tell-tale

surface texture of foam, even with a nice paint job, ruins the authenticity of an

otherwise beautifully factory-finished scale F4-U Corsair or P-38 Lightning. Sorry,

that's just the way it is. Sig Manufacturing was, in the aforementioned era, one

of only a couple major balsa suppliers (Midwest being the other). The Sig catalog

had a really nice primer on balsa with a treatment of history, tree harvesting and

production, and technical information like density of balsa sheets, sticks, and

blocks. That information from an early 1970s catalog is reproduced here. I also

have a page on balsa wood density

and weight, and a reproduction of an article on

balsa tree foresting and

harvesting by Sig Manufacturing from one of their 1970s era catalogs.

Important Facts About Balsa Wood

For people who like to know everything! For people who like to know everything!

Courtesy of International Balsa Corp.

What Makes Balsa So Unique?

Balsa is the softest and lightest commercial wood in the world. It weighs only

4 to 18 lbs. per .cubic ft., averaging about 9 lbs. per cu. ft. But pound for pound,

it is stronger in some respects than pine, hickory or oak - it is one of the strongest

woods in the world for its weight, particularly in tension. It is resilient - with

high compressibility and recovery. It is buoyant - 1 cu. ft. will carry over 50

lbs. of water. Its high insulation value is equal to cork. Balsa's high electrostatic

qualities make it an insulator against electricity. Balsa absorbs shock and vibration

well. It is inert - no fumes, dust or reaction. It is stable and will not warp readily.

It is durable - withstanding heat, cold, dampness long storage and weathering. Balsa

is easily workable and can be processed with the same tools and techniques as ordinary

woods. Balsa can be processed to simulate many other materials and takes these finishes

and processes well.

The "Friendly" Wood The "Friendly" Wood

Most people like wood anyway. It has such a friendly feel. But Balsa has this

"friendliness" to a higher degree ... it is pliant to the will of man, so light,

so soft, so easily worked into so many things. Lay a piece of Balsa before a man,

woman, boy or girl, and they can't resist picking it up, hefting it, feeling its

smoothness, pressing their finger into it to test its submissiveness. With Balsa

every person is an artisan, an artist. Balsa Wood is used so extensively in building

models of all kinds because the hobbyist has found that it will give him a lighter,

stronger job, and greater flexibility in its construction and performance, than

with any other material.

The Perfect Nurse

In this age of science, when man is always trying to improve on Nature, it is

unusual to find a substance where Nature has outdone man. People ask "What process

do you use to make Balsa so light?" There is no process. Balsa is just naturally

light. Balsa grows only in the humid rain forests of South and Central America.

Actually Nature did not design Balsa as a crop tree. While it needs a lot of moisture,

it grows only in well-drained sites. When the young seedlings of the forest giants

start to grow on the forest floor, they need a nurse tree to shade them and keep

them from drying "out in the hot tropical sun. That nurse tree must grow fast, with

a spreading crown and large leaves to provide shade for the babies.

Yet there can't be too many leaves because they would shut out air and sunlight

from their charges. While the nurse tree must grow fast, it can't put too much beef

into its body. The accent is on Volume, not on strength. And it must not live too

long .... just long enough to see the seedlings through to where they can take care

of themselves. The Balsa tree goes all out to live up to the characteristics of

a perfect nurse.

Speed vs. Strength

What happened to the wood in the Balsa

tree when it sacrificed substance for speed of growth? Under the microscope we find

the basic parts the same as in all woods - Nature is conservative in a way, and

when She finds a good, basic design, She adapts it in various ways, so that She

obtains a variety of forms. She begins with a basic material, cellulose, which weighs

97 lbs. per cubic foot. She molds it into various shapes - tubes, cells, long, tapering

fibers. So far the parts are the same for all the different kinds of wood, and if

She were to stop there, there would be only one kind of wood. But now She diversifies

- She makes one part large, the other small, She thickens the cell wall on some,

slims them down on others. She leaves a big opening here, a small opening there.

She bunches some together, others She spreads out. Here and there She adds a pinch

of salts, some crystals, pumps in some resin or tannin, and by arranging the same

few elements in hundreds of different ways, She comes up with thousands of different

species. What happened to the wood in the Balsa

tree when it sacrificed substance for speed of growth? Under the microscope we find

the basic parts the same as in all woods - Nature is conservative in a way, and

when She finds a good, basic design, She adapts it in various ways, so that She

obtains a variety of forms. She begins with a basic material, cellulose, which weighs

97 lbs. per cubic foot. She molds it into various shapes - tubes, cells, long, tapering

fibers. So far the parts are the same for all the different kinds of wood, and if

She were to stop there, there would be only one kind of wood. But now She diversifies

- She makes one part large, the other small, She thickens the cell wall on some,

slims them down on others. She leaves a big opening here, a small opening there.

She bunches some together, others She spreads out. Here and there She adds a pinch

of salts, some crystals, pumps in some resin or tannin, and by arranging the same

few elements in hundreds of different ways, She comes up with thousands of different

species.

In Balsa, Nature has cut every possible corner to do a fast, efficient job. Everything

that would build up weight has been eliminated. The cell walls have been slimmed

way down. The spaces inside the cells have been enlarged, so that the ratio between

solid matter and space, is as small as possible. Most woods have gobs of heavy,

plastic-like cement, called lignin, holding the cells together. In Balsa, lignin

is at a minimum. The result is a wood which may weigh anywhere from 4 pounds per

cubic foot, to 12 pounds per cubic foot. (As the tree grows older, passes its prime

and begins slowing down in growth, it may develop wood as high as 18 lbs. per cubic

foot.) Compare this with one of the lightest, native woods, Spruce, which weighs

23 lbs. per cubic foot. But, you will ask, "Hasn't Nature gone too far and robbed

the tree of all its strength?"

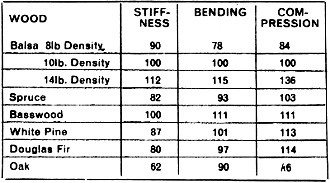

Table I - Strength/Weight Figures for Various Woods

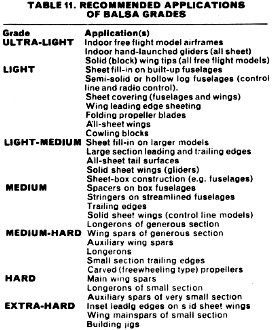

Table II - Recommended Applications of Balsa Grades

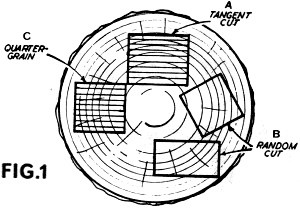

Fig. 1 - Balsa log cut types.

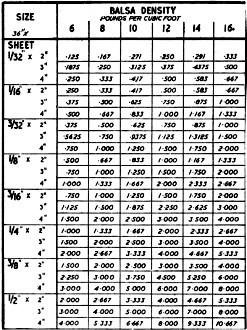

Table III - Balsa Sheet Density

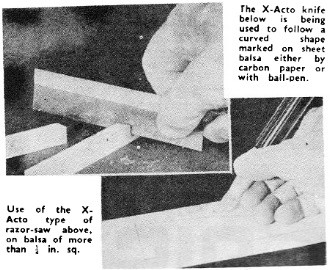

Use of the X-Acto type of razor-saw (top), on balsa of more than

1/4 in. sq.

The X-Acto knife (bottom) is being used to follow a curved shape

marked

on sheet balsa either by carbon paper or with ball-pen.

(note: these two images were printed upside-down in the catalog)

Table IV - Balsa Strip Density

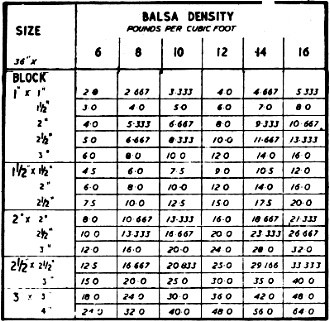

Table V - Balsa Block Density

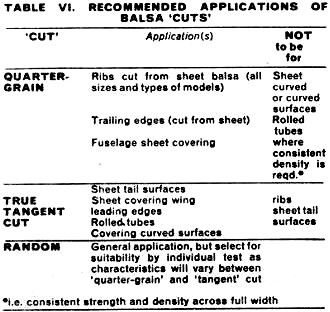

Table VI - Recommended Applications of Balsa 'Cuts'

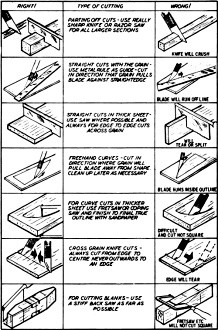

Figure 5 - Right and Wrong Way to Make Cuts in Balsa

Nature has many tricks up its wide sleeve. It has given the Balsa tree a tough,

stringy bark, which unlike many trees does not flake off but builds up as the tree

grows. She pumps the Balsa cells full of water until they become rigid - like an

automobile tire full of air. (The green Balsa Wood may contain as much as five times

as much water by weight as wood substance. Compare this with green, native woods,

which may contain only three-quarters the weight of water as against the weight

of wood.) But the most important to us is that She takes the Balsa cells and by

twisting them about each other, arranging them with consummate skill, she gives

the wood itself an inherent strength.

Romance of Logging

There is no such thing as woods of pure Balsa trees. They grow singly, or in

very small, widely scattered groups. It is a matter of finding one tree here, another

tree 100 yards over the hill. Because of the way the individual Balsa trees are

scattered throughout the jungles, it is not possible to use many of the established

logging procedures used in this country. Machinery requires a more or less concentrated

stock of logs. It also requires people who are skilled in its use and maintenance.

To the surprise of our efficiency experts, we have found that the best way to log

Balsa is to go back to the methods of Paul Bunyan. Chop them down with an axe -

no saw; haul them to the river by ox team; float them down the river to the mill

in rafts.

This procedure cannot help but bring back the old, romantic days of logging about

which so much has been written in the United States. You have the same hairy-chested

logger, maybe a little shorter than his counterpart in song and story, but still

rough and tough and hard as nails. You have the same ox skinner with his long, bull

whip and his marvelous mastery of profanity in three languages. You have the river

rats floating the rafts down to the mill and whom, for shear guts day after day,

I challenge you to match anywhere in the world. These are the men whose muscle and

blood and sweat make your model airplane.

Hurry Up, Amigo

Because of their vulnerability to attack by insects and fungi, it is very important

that the Balsa logs be taken out of the woods and delivered to the sawmill just

as quickly as possible. Unlike the logging of other timbers, you cannot cut down

a great number of logs and stack them for transportation while awaiting a propitious

time. They must be taken out of the woods immediately, preferably the same day,

and dragged to the river. They must then be floated to the mill without delay. The

best logs are received at the mill within ten days to two weeks after they have

been cut.

At the sawmill we don't waste any time with them either. The rafts are broken

up immediately arid the logs are dragged up a long ramp to the head saw, where they

are squared. From the head saw they go to a gang saw, which converts them into boards.

Importance of Kiln Drying

The next step is one of the most important in the process of manufacturing Balsa

boards. It is kiln drying, by means of which the moisture is removed from the wood.

Without kiln drying Balsa would not have its characteristic lightness, nor its strength.

Kiln drying kills bacteria, fungi, and insects; because the wood is dry it prevents

them from returning. Balsa that is not kiln dried, or improperly kiln dried, bears

very little resemblance to the finished product which most of us know. But kiln

drying is a rather fine art. For the sake of economy, the wood should be dried as

quickly as possible. but if it is dried too quickly, it may be irreparably damaged

- slits appear in the wood, and the boards twist and warp. You may have a condition

where the outside may be dry and the inside damp - this is knows as case hardening.

When a case hardening board is cut, it will twist like a cork screw.

Drying is accomplished by the application of heat through steam heat exchangers,

and through the regulation of the amount of humidity. If the heat is held at too

low a point, it may increase fungus attack instead of killing it. If the heat is

too high, it will kill the natural elasticity of the wood. If the humidity is too

low, the wood will dry out too fast, and will result in all the drying defects mentioned

before. If the humidity is held too high, the wood will not dry. The dry kiln operator

then has to walk a tight rope between the two extremes, manipulating his valves

and controls so that the fastest, most efficient drying is accomplished, with a

minimum of damage. This is done by placing the Balsa lumber, stacked in layers,

on cars with spacers between the layers, to permit the passage of air. The cars

are placed in the kilns, which are long and tunnel-like insulated compartments where

they are subjected to controlled heat, humidity and air circulation.

After spending from ten days to two weeks in the kilns, the lumber is removed,

cooled gradually and is then reworked to remove defects; it is planed to thickness

and is then packed in bales for shipment via ocean steamer. On arrival in this country,

it is sold to other manufacturers, who cut the wood into the many useful things,

for which Balsa is so well suited.

Balsa (or balsawood, whichever you prefer to call it), has been the standard

material for model airframe construction since it first became available commercially

in suitable cut sizes some thirty-five years ago in this country and even earlier

in America. Although, botanically at least, balsa is only about the fourth or fifth

lightest wood in the world it is the first of all the woods which combine strength

with lightness. On a strength/weight basis, in fact, balsa compares favorably with

most other woods - even oak (see Table I). This is one of the main reasons why it

is so suitable for aeromodeling, where strength is required for minimum weight.

Many other materials which are as light as, or lighter than balsa, also fall down

on this question of combining strength with lightness and cannot be used in small

sections - expanded polystyrene, for example.

The other great advantage of balsa is the ease with which it can be cut or carved,

and joined with quick drying cement. Having a fairly open structure, balsa cement

impregnates and adheres strongly to balsa with the result that properly made glued

joints are as strong or stronger than the wood itself. With balsa readily available

in a wide range of sheet, strip and block sizes, very few tools are required for

working balsa either in solid form or for the assembly of built-up frames, etc.

At the same time, however, there are disadvantages. The balsa tree is very fast

growing, reaching a height of 15 feet of more within a year and growing to between

60 and 90 feet within the next six to ten years. After that time the tree begins

to deteriorate and rot. As a result both the density and quality of the lumber obtained

by felling balsa trees can vary enormously.

SIG - The Most Famous Name in Balsa! SIG - The Most Famous Name in Balsa!

Reprinted from Aero-Modeler

The actual density of balsa can vary from as little as 4 lb./cu. ft. to as much

as 24 lb./cu. ft. (which is about the same as obeche). Practically all the commercial

balsa available, however, falls within the range of 6 to 16 lb./cu. ft. with the

overall average tending to run about 9-10 lb./cu. ft. The strength properties of

balsa vary directly with density - the heavier the wood the stronger it is.

Balsa is normally graded by density, although, the actual descriptions are largely

arbitrary and not always identical between different suppliers, or different model

designers specifying grades to be used. The most general commercial classification

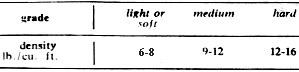

is "light", "medium" and "hard", as below -

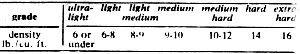

The more expert modelers adopt a wide. range of grading, typically as below -

Logically one selects the lightest grades for the lightly stressed parts (e.g.

block wing tips, sheet fill ins, etc.)and the heavier grades for spars and longerons.

Even here, however, practice can differ. Some modelers prefer to use very hard balsa

for longerons and spars and keep weight to minimum by reducing the actual size of

the sections used. Others prefer to use a lighter grade and compensate for strength

by using larger section.

Note: the strength/weight ratio of 10 lb. cu. ft. Balsa is rated at 100 and the

strength/weight ratios of other woods calculated accordingly. Thus a figure of less

than 100 shows a performance inferior to 10 lb balsa on a strength/weight basis;

and a figure of over 100 a superior performance

Both systems have there advantages and disadvantages. The use of hard grades

and small sections actually gives the best overall strength to weight ratio (see

Table I). On the other hand, the smaller size spars may be more difficult to handle

for building and also lack local stiffness. Using larger sizes normally gives greater

stiffness and local strength, although it is also easy to add excess weight as well

unless the grade is carefully selected. Also if too light a stock is chosen in the

interests of saving weight, the resulting structure may be weak. For most purposes,

however, Table II can be used as a guide for balsa grade selection.

In practice, grade selection can only be made with reference to actual weights

of individual sheets or strip lengths. To save having to work out density in each

case, consult Tables III, IV and V.

A tip to remember here is that as far as grading is concerned, suppliers of cut

balsa tend to favor selection of the harder grades for the smaller sizes (or thickness)

of strip and sheet as being easier to handle. Thus one is more likely to find mostly

"hard" grade in 1/16 in. sq. for example, and more medium to soft in 3/8 in. sq.

Similarly, the proportion of "soft" is likely to be higher in 3/8 in. and 1/4 in.

sheet than in 1/32 in. or 1/16 in. sheet.

In point of fact "cut" is more important than appearance in the case of sheet

stock since this largely controls the rigidity, or strength of the sheet. And cut

depends on the way the original lumber is cut from the log and then finally machined

- see Fig 1. If the "cut" is such that the annular rings effectively run across

the thickness of the sheet (tangent cut) the sheet will be fairly flexible, edge

to edge. It, on the other hand, the cut is such that the annular rings run across

the thickness of the sheet (radial or quarter-grain sawn), the sheet will be rigid.

It will also be appreciated that a piece of lumber cut from either section A or

section C of the log can have a final cut for turning into sheet which is either

tangent or quarter grain, depending on which face the cut is made from. If the section

of lumber is "random cut" the grain direction is less clearly defined and irrespective

of the direction of final cut the sheets will have intermediate properties between

"tangent cut" and "quarter-grain".

It is difficult to distinguish between random cut and tangent cut by appearance,

or even by simple bending tests, but quarter grain shows up quite clearly by the

speckled appearance of the surface. True quarter-grain sheet, in fact, would be

too stiff to bend to even moderate curvatures without splitting - and quite impossible

to roll into a tube shape as can be done with carefully selected light density tangent

cut stock.

Again "cut" recommendations are summarized in the form of a table for convenience

of reference (Table VI). The point to bear in mind is that "cut" and "grade" are

interrelated, so that the best choice of balsa for a particular job is based on

both. This applies particularly in the case of sheet balsa parts. The stiffness

or otherwise of spars is best judged by actual test - e.g. to obtain a pair of matched

spars, select two of equal weight and appearance .

In this manner, and in the latter case in particular this may mean examining

and testing a considerable number of individual strip lengths in order to arrive

at a set of four more or less identical pieces. Many experienced modellers, in fact,

prefer to cut longerons and spars from sheet stock in order to achieve complete

matching. In general, however, this is only advantageous where relatively small

sizes are involved - e.g. longerons not greater than 5/32 in. sq. section and spars

not more than 1/8 in. thick. Cut longerons and spars in thicker sheet generally

suffer from inaccuracies due to the difficulty of making long accurate "square"

cuts in thicker sheets.

In cutting a set of matched longerons, the sheet should be marked before cutting

(e.g. with a ball pen) so that the final lengths are identified end for end and

used the same way round for a complete match - Fig. 2. The same applies to cutting

parallel spars. In the case of tapered spars however, the best match is obtained

by cutting the two spars about a common "bottom" line rather than an angled cut

separating the two - see. Fig. 3.

A modeling blade with a fine taper is usually best for cutting fine sheet. The

same blade may also be used for parting off longeron and spacer sections up to 1/8

in. square; although some modelers find it easier to work with a less tapered blade

- Fig. 4. The squarer blade is also better for cutting thicker sheet as the fine

tapered blade can more readily run off "square". The razor saw comes into its own

for cutting larger sections.

The best direction of cut is normally obvious, but some specific recommendations

are. summarized in Fig. 5, together with explanatory notes. The main thing is to

avoid stressing balsa sheets across the grain (in which direction it is weakest),

so cross grain cuts should always be made from the edge inwards, rather than outwards

towards an edge. Also, when cutting at an acute angle to the grain, make the direction

of cut so that the grain will tend to pull the blade away from rather than into

the component shape.

Resources for Balsa Wood on the Airplanes and Rockets website:

|