|

Is the

BOMARC an

airplane or a rocket? If it is an airplane, then it is the pilotless type (aka "drone").

If it is a rocket, then it is the ultimate in controlled trajectory hardware - at

least in its day. The DoD referred to it as a surface-to-air guided missile. The

name is a combination of "BOeing Airplane Company" and "Michigan

Aeronautical Research

Center." Clever, non? If memory serves me correctly (it's

been 30+ years), the

AN/TPX-42 IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) secondary radar system

(built by Gilfillan) I maintained as an air traffic control radar technician reserved

a special "X" bit in its data packet to designate the BOMARC - and maybe other guided

missiles. That might have been a military secret at the time, because the Air Force

instructors acted like they were divulging proprietary information when discussing

why that bit was present in an otherwise generic data stream. Yo, Don H. and

other retired radar techs: Do I recall correctly? Is there anything you would like

to add?

Bomarc IM-99

By Peter M. Bowers By Peter M. Bowers

In this day of missiles, identification by popular names rather than type numbers

is widespread, as in the case of "Thor" and "Atlas." Not all of the names, however,

are chosen because they symbolize the power or the purpose of the missile. "BOMARC,"

a coined word, is simply a combination of the names of the originators of the Air

Force's newest weapon system, the IM-99 interceptor missile, developed by the Boeing

Airplane Company and the Michigan Aeronautical Research Center.

Bomarc's buddies in North American Air Defense Command include

RCAF's FC-100 (far left) and USAF F-102.

Use of names instead of numbers for military aircraft is not new, some popular

names having been applied in addition to the symbolic military type and model designations

since the 1920's. One of the earliest examples was the name "Hawk," which was given

to a long line of related Curtiss military, naval, and civilian planes. The practice

was more or less unofficial before WW-II, but during the war years it was encouraged

by the Government both as a guide to aircraft recognition by civilians and as a

security measure designed to hide the development status of any particular design

from the enemy. "Lightning" was applied to all Lockheed P-38's, for example, rather

than resorting to such detailed identification as P-38L-5. Modem missiles are referred

to almost exclusively by official and unofficial sources alike by names rather than

by numbers.

GAPA Beginning.

Boeing's experience in the missile field goes back to 1945, when a small group

was assigned the task of developing a rocket-powered anti-aircraft missile. In the

absence of an official type designation, this was called the "GAPA," an abbreviation

of the name Ground-to-Air Pilotless Aircraft. Altogether, 112 of these guided interceptor

rockets were built and fired before the Air Force cancelled further development

in 1949 because of conflict with other short-range missile programs that had been

put under the jurisdiction of the Army.

Boeing, meanwhile, had applied its accumulated GAPA experience to the preliminary

design of a larger missile that could seek out and destroy invading aircraft hundreds

of miles from the target in the manner of a long-range fighter plane instead of

merely defending the target itself as a rocket-powered guided anti-aircraft shell.

B Meets ARC/UM.

Boeing was concerned primarily with the missile itself, which was only one part

of the overall "Weapon System" that must involve detecting, launching, and guidance

as well as the "bird" that carries the warhead to the target. During discussions

of the overall problem at Wright Field following cancellation of the GAPA Project,

Boeing engineers were advised by Air Materiel Command personnel that the Aeronautical

Research Center at the University of Michigan had been working on the guidance system

for just such a missile. It was suggested that the Boeing and Michigan people combine

their efforts and come up with a joint proposal for an entirely new and complete

weapons system.

Result was a pilotless interceptor airplane that could carry an atomic warhead

to meet an invading bomber five hundred miles away. When the developmental contract

was let in January, 1951, the new interceptor was given the standard fighter designation

of F-99, for, in keeping with the concepts prevailing at the time, no distinction

was made between manned and remotely-controlled aircraft. The choice was not illogical,

since Bomarc possessed practically all of the characteristics of a normal airplane

- wings, fuselage, tail surfaces, and power plant. Only the landing gear and pilot

were missing. Remote-control airplanes were nothing new either. Obsolescent service

types and specially-built drones had been used as radio-controlled target planes

for years, and the change to liquid-rocket boost and ramjet power was a less radical

change from standard jet propulsion than the change from propellers to jets had

been. However, the different operational concept of the new weapon system soon caused

the F-99 to be reclassified as an "Interceptor Missile" under the designation of

IM-99 at the same time that the pilotless Martin. B-61 "Matador" bomber was redesignated

TM-61 for "Tactical Missile."

Bomarced F-94!

First firing of the new missile took place on September 10, 1952, at the now-famous

Cape Canaveral site in Florida even though Bomarc was not complete at the time.

The two Marquardt ramjets and' the guidance system were not installed since the

purpose of the firing was merely to test the rocket motor and the basic aerodynamic

characteristics that had been developed as a result of wind tunnel tests. Separate

testing of the guidance system took an interesting form - instead of losing the

complete and very expensive test vehicle after each flight as was the inevitable

result of most missile testing, a Bomarc nose section containing the missile guidance

system was built into the nose of an Air Force Lockheed F-94 "Starfire" jet. The

guidance system was then hooked into the Pilot Direction Indicator on the instrument

panel of the F-94, and the accuracy of the system was measured by observation of

the course that the F-94 took while the pilot was following the course given by

his instrument. In this way, malfunctions that would have sent an unmanned missile

far off course could be detected and the causes analyzed after the test vehicle

was brought back to the home field after the test.

If all worked properly, the F-94 followed a collision course toward the target

airplane, usually a conventional piloted airplane when used in conjunction with

the F-94 instead of being a radio-controlled drone (usually an obsolescent B-17)

when used with the missile itself. The pilot was advised of his position relative

to the target by ground radar, and knew without seeing the target through his windshield

when to change course to avoid a collision. While Bomarc missiles were launched

to intercept targets on inbound courses and generally approached them head-on or

at least from a forward angle, the F-94 frequently closed on the target from the

rear to reduce the terrific closing speeds produced by head-on approaches and increase

the time available for system evaluation during the approach. The F-94 served in

this capacity for nearly three years before being replaced by a Martin B-57B fitted

with a similar Bomarc nose.

Initial Flight.

First successful flight with ramjet power was made on February 21, 1955. Since

ramjets won't work at low airspeeds, Bomarc is launched and brought to nearly supersonic

speed by an Aerojet liquid-fuel rocket built into the tail. By the time the rocket

fuel is almost expended, the missile has sufficient speed to permit the two ramjets

to operate. These ramjets, mounted on pylons projecting from the fuselage, continue

to accelerate the IM-99 far into the supersonic range for the remainder of its flight

to the target.

Prior to the launching, information relative to the speed, course, and altitude

of the target are automatically fed, or "programmed," into the Bomarc's guidance

system. Following the launching, the missile is guided by ground control to the

area where the preliminary calculations show that the target is expected to be.

As it approaches the target area, the guidance system in the nose takes over, disregarding

further ground instructions, and the bird is strictly on its own.

While an operational missile does not need to score a direct hit on a target

in order to destroy it, the guidance system was so accurate that a number of the

target airplanes were destroyed by direct hits on the fuselage or by very close

misses that nicked a wingtip. The hits were unintentional, as the missile was required

only to come close enough to the target to be able to destroy it by the blast of

the warhead touched off by a proximity fuse. No actual warheads were used during

the testing. While the hits and-near-misses contributed to a spectacular record

for accuracy, they hampered the test program by reducing the supply of obsolete

but still costly target airplanes and destroying the photographic records obtained

by automatic cameras aboard the targets.

The maneuverability of Bomarc is remarkable, enabling it to change course more

rapidly than an invading bomber taking evasive action. Once the target-seeking system

has "locked-on" to the target, the missile is guided through changes of course as

though by a human hand, but at much greater speed, thanks to the unique form of

the controls. Instead of the standard ailerons, elevators, and rudder of the conventional'

airplane, the IM-99 utilizes full-floating tips on each surface, now called "Tip-Type"

controls. This system is by no means new, having been tried before and during WW-I

and used on a number of gliders in the between-wars years. The main disadvantage

of this type of control for piloted aircraft was the lack of "feel" for the pilot,

who could easily overcontrol at high speeds and overstress his plane. Another problem,

especially on the glider, was flutter resulting from necessary play in the control

system. Boeing licked the flutter, and with an electronic instead of a human pilot,

the "feel" was no longer a problem. Overstressing the aircraft through full displacement

of the powerful controls at high speed was not a problem for the missile either,

since it was built to withstand loads far in excess of those that could be tolerated

by a human pilot.

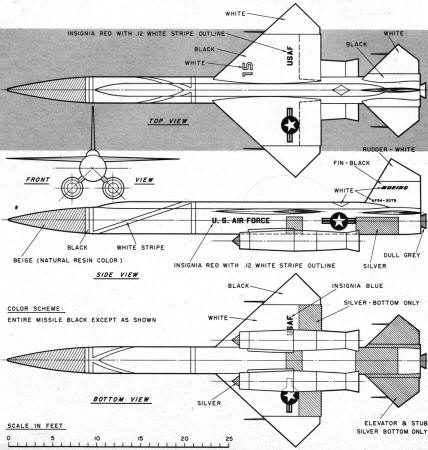

Specifications.

In size, the IM-99 approximates a small piloted fighter such as the Lockheed

F-104. Wingspan is 18' 2", the length is 47' 4" and the gross weight, including

warhead, is approximately 15,000 pounds. In spite of being a missile, the IM-99

carries standard aircraft markings and serial numbers as shown in Jim Morrow's drawing.

This practice is standard for all Air Force "airplane" type missiles such as the

TM-61 "Matador" and the SM-62 "Snark."

The IM-99 was ordered into production after nearly five years of intensive testing

and development. An initial order of $7,109,195 was placed on May 6, 1957, and was·

increased by $139,315,444 in August. Thanks to production experience gained with

the numerous prototype and test models, Boeing was able to deliver the first production

model to the Air Defense Command on December 30 of the same year and launch a new

era in the history of military aviation.

Posted May 20, 2024

(updated from original post

on 3/5/2016)

|