|

February 1939 Popular Science

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early

electronics. See articles from

Popular

Science, published 1872-2021. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Leonardo da Vinci

is usually credited with producing the first illustration of a helicopter concept.

It employed a rotating helical corkscrew device at the top in order to enable the

craft and occupant to "screw his way aloft, in much the same manner as

Archimedes designed

his eponymous helical screw device to lift water from a lower level to a higher

level. Water, being dense and cohesive with itself, was easily elevated, whilst

air, not being dense or cohesive, did not yield to the same technique. In fact,

if the "aerial screw" were able to spin rapidly enough and was of an efficient aerodynamic

design, it would work. Here is a

4-screw drone to prove it. These "Windmill Planes" presented in the

February 1939 issue of Popular Science magazine represent the state of

the art at the time. Surprisingly omitted is an example of

Igor Sikorsky's helicopter design, which he first flew successfully in

September of that year.

Windmill Planes

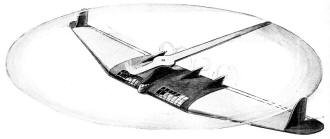

Open New Field in Aviation: Proposed helicopter with gas-filled

spiral wing. If engine fails, base containing motor and tanks is dropped

Whirring gyro-planes, and amazing wingless air machines that soar straight up,

hover motionless, and even fly backward, may soon open a new chapter in the history

of aviation. That is the prediction of 150 engineers and scientists, gathered a

few weeks ago at Philadelphia, Pa., to discuss the remarkable recent advances of

rotating-wing aircraft, and the problems that still confront their builders, in

the first meeting of its kind ever held.

Nor was this mere prophecy. Spurred on by a $2,000,000 grant from Congress for

the study of all types of "whirligig" aircraft, for possible use by the Army, Navy,

Coast Guard, Department of Agriculture, and a dozen Government bureaus, active production

is soon to boom again.

The first machines to be developed in the big program will probably be gyroplanes,

the fantastic "flying windmill" type of craft introduced in this country by the

late Juan de la Cierva, in 1929. Holding forth a brilliant future, the autogiro

and similar machines were beset with technical shortcoming that had to be solved

before they could become a commercial success. After ten years of quiet experimentation

and development, the knottiest problems have been overcome. Strength and efficiency

have been increased, and control has been made easier and more certain. Speed has

been increased from seventy or eighty miles an hour to 135.

Where greater speed is required, without sacrificing the ability to land slowly

and safely on the roughest or most restricted terrain, a convertible plane, designed

by Gerard P. Herrick, New York engineer, is the answer. Normally a biplane of conventional

appearance, it has the upper wing mounted on a single pivot bearing at its center.

This wing may be released and set rotating at will by the pilot, converting the

ship instantly from an airplane to a gyroplane.

Autogiro in flight. It is a cross between helicopter and plane.

A transport of 1950, as forecast by an American inventor. It

has a rotor wing for take-offs and landings.

Left, a girl flyer demonstrating the Focke helicopter in

a German hall.

Adapted for commercial and private flying, the Focke helicopter

will look something like this. Rotating-wing flying machines may supplement regular

planes for many uses. (rotors on wingtip)

One of the greatest hopes of the new program, however, is the helicopter, until

recently considered a dream almost as wild as that of perpetual motion. Now, it

is here. Since the middle of 1937, a machine that can dart straight up, stand motionless

in still air, fly sideways and backward, has been flying all over Europe. E. Burke

Wilford, of Philadelphia, has developed a similar machine, and expects to begin

production of helico-gyres - machines that ascend as helicopters and fly or land

as gyroplanes - within a few years.

Louis Breguet, famous French aeronautical designer, goes even farther. Before

the French Academy of Science he recently presented a design for a helicopter transport

that would lift a total load of sixteen tons, fly 310 miles an hour, and excel the

efficiency of a conventional airplane!

It is the Focke helicopter, however, that opens the most amazing field of development.

Until 1936, many helicopters had managed to get into the air, but once there they

lacked control almost completely. Either the torque produced by the spinning rotor

whirled the machine around, or a gust of wind overturned the whole thing and crashed

it to the ground.

Unlike most previous machines, the Focke helicopter is the result of years of

theoretical research, of experiments in wind tunnels and in "flights" while the

machine was tied to the ground. On June 26, 1936, it made its first free flight.

A year later it won all existing world's records - rising to an altitude of 8,600

feet, hovering motionless, flying forward at ninety miles an hour, and backward

at twenty! So perfect was its control, that in February 1938, a girl flew the machine

successfully throughout a Berlin hall, at times hovering only eight feet off the

floor while leaning out the cockpit and talking with her associates!

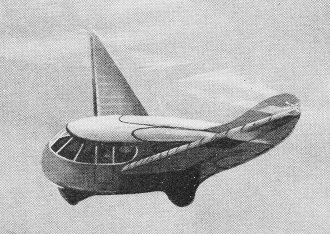

Both Biplane and Gyroplane: Concept drawing.

Prototype gyrplane.

This queer hybrid is a convertible biplane-gyroplane. The upper wing is mounted

on a pivot so that it can be released and set rotating at will, thus converting

the craft into a gyroplane

Still another approach to the problem is revealed in the plans of a California

inventor for a helicopter having a gas-filled corkscrew wing that whirls on a vertical

axis above a globe-shaped fuselage. In this odd ship, rudder and stabilizing surface

are mounted on a yoke that pivots on the poles of the spherical gondola to guide

the craft in any desired direction. In case of engine failure in flight, the base

containing the motor and the fuel tanks can be dropped, allowing the rest of the

craft to drift safely down like a parachute.

Somewhat slower, inherently safer, and capable of making landings and take-offs

in extremely restricted areas, the rotating-wing machine does not compete with the

airplane but supplements it in a field of its own. Among suggested uses are for

air taxi or bus service from suburbs to city, military observation, mapping, forestry

work, sea rescues, and ship-to-shore service. For private flying, of course, its

safety and ease of landing make it ideal.

|