|

At launch in 1962 when this

article appeared in Popular Science magazine, Mariner 2's planners imagined

Venus cloaked by benign oceans or lush swamps - temperatures perhaps only "hot-house

Earth" elevated. Microwave echoes from Earth hinted at a 600 °F surface, yet

editors clung to hope that dense clouds concealed cooler seas and maybe biology.

Infrared spectra were interpreted as carbon-dioxide greenhouse gases in a thin,

relatively clear layer; the idea of surface pressures a hundred times Earth, sulfuric-acid

rain, and global 860 °F basalt plains lay outside anyone's paradigm. A magnetosphere

like Earth's was expected; Venus instead proved geologically inert and wind-scoured,

with sluggish super-rotation. Fifty years later, radar from Magellan and Earth-borne

interferometry have overwritten 1962 optimism with images of barren basalt plains

and scorching CO₂ night.

Keeping a Date with Venus

First to fly within exploring range of another planet, our keen-eyed

Mariner 2 spacecraft is Keeping a Date with Venus

Dramatic climax of Mariner's voyage takes craft across face of

Venus, from dark to sunny side.

By Wesley S. Griswold

The world will get its first close-up look at another planet - if luck holds

out - on December 14 between 10 and 11 a.m. Pacific time.

At that likely-to-be-historic moment, the gold, silver, and blue U.S. space-craft

Mariner 2 has a date with Venus. It will fly past Earth's sister planet at such

close range, less than 21,000 miles, that Venus will loom up before it as big as

a basketball at arm's length. Instruments aboard it will scan Venus' cloud-wrapped

face.

And if no mishap has stilled the craft's radio, Mariner will send us the most

exciting news in the annals of exploration. It's expected to tell us at last what

mysterious Venus' surface and atmosphere are like, and answer the most fascinating

question of all: Can there possibly be life on Venus?

Four other attempts to explore Venus, one American and three Russian, have failed.

A Russian try last year got a spacecraft within 62,500 miles of Venus, but to no

avail - its radio had gone dead long before. Remembering that misfortune, Mariner

2's sponsors were sweating out the suspense of its 109-day voyage as this issue

went to press - but thus far, since its August 27 launching, all was going incredibly

well.

The $10,000,000, 447-pound craft on its way to Venus, built and operated for

NASA by Caltech's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, looks like a flying weather vane. It

measures 16 1/2 feet the longest way - the span of its blue-tinted solar panels.

Positioned by tiny attitude-controlling nitrogen jets, Mariner keeps these panels

always facing the sun. They turn sunlight into electricity - up to 222 watts - to

power a radio transmitter so small you could hold it in your hand, a 41-pound payload

of instruments, and Mariner's computer brain. Hinged and kept trained on Earth,

a long-range antenna sends back the instruments' reports. With almost-human talents,

the electronic brain directs all operations, following preflight instructions and

in-flight radio commands.

If an observer could watch the climax of Mariner's 180,000,000-mile journey to

Venus, he would see a breath-taking drama enacted. Gradually overhauling Venus,

Mariner will swing in toward it on a near-collision course - like one express train

racing another to an oblique crossover. Barely before Mariner reaches the crossing,

the awesome bulk of Venus will whiz across its path at more than 78,000 m.p.h. Flashing

over the crossing in hot pursuit, the even faster-moving spacecraft will catch up

with Venus - and pass alongside the planet, on its inward and sunlit side.

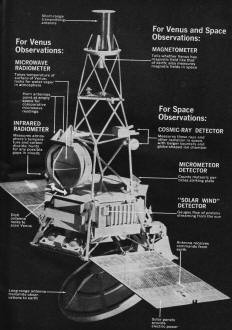

Venus-observing instruments of Mariner 2, together

with other instruments and principal flying gear, are shown in view opposite - on

a model of the spacecraft. Bowl resembling search-light, near center, is pivoted

dish antenna that rocks back and forth to scan Venus with radiometers that take

the planet's temperature and tell what's in its atmosphere.

Making "Eyes" at Venus

During the spectacular encounter, an eyelike instrument - a little dish antenna,

20 inches across and three inches deep, called a microwave radiometer - will ogle

Venus. Pivoted to be rocked up and down, it will scan the planet's disk in a zigzag

fashion, progressing from the dark side to the sunny side. Mounted on the edge of

the dish, so that it will always be looking at the same portion of the planet, is

a second "eye" called an infrared radiometer.

Both will pick up Venus and start their scanning at a range of 24,516 miles,

hardly more than the planet's circumference. They'll end observation just 41 minutes

and 40 seconds later, on the sunny side of Venus and only 21,291 miles away. (The

dish's right-angle mounting, and Mariner's heading, cause them to lose sight of

Venus a trifle before the closest, 20,918-mile, approach.)

Since clouds hide the planet's surface, looking at Venus with a camera would

reveal little. Radiometers provide subtler ways to pierce the cloudy mask. The microwave

instrument picks up the planet's natural or "thermal" radio emission - resulting

from its own heat-at two selected wave lengths of 13 1/2 and 19 millimeters. The

infrared instrument detects heat radiation at the shorter wave lengths of 8-9 and

10-10.8 microns.

By ingeniously piecing together the surprising variety of clues obtainable at

these particular wave lengths, scientists hope to settle wildly contrasting speculations

about Venus' surface: Is it a steaming swamp, an unbroken ocean, or a dusty and

sealing-hot desert?

Taking Her Temperature

Measuring the intensity of Venus' radio emission will tell the temperature of

the planet - the main task assigned to the microwave instrument. That will check

out an astonishing 600 degrees for Venus' surface, measured from earth by the same

new technique - if correct, a shattering blow to any hope of finding life on Venus,

and even of landing there in the future. If the long-range reading actually comes

from higher in the atmosphere - or is a false one, perhaps thrown off by an extraordinary

concentration of electrons in Venus' ionosphere - close-in measurements will show

it. As a double check, while the microwave instrument is taking the temperature

at Venus' surface, the infrared instrument will take temperatures in its atmosphere.

Does Venus have water, vital to life as we know it? The microwave instrument

should reveal that, too. If so, reception should be weak or nonexistent for the

13 1/2 mm wave length, which would be absorbed by water vapor in Venus' atmosphere.

The other, 19 mm wave length is unaffected by water vapor.

Similar telltale differences in the infrared instruments' two sets of readings

should reveal whether Venus' atmosphere contains enough carbon dioxide to account

for an oven-like surface temperature, by a "greenhouse effect." Carbon dioxide will

mask the 10-10.8-micron band but not the other, providing the needed clue. By the

same artifice, the instrument will seek to learn whether there are any breaks in

Venus' cloud blanket, through which its surface might occasionally be glimpsed.

A third Venus-observing instrument, in a metal cylinder, is a magnetometer. It

will tell" us if Venus has a magnetic field like Earth's compass-attracting one.

That will throw light, not only on the planet's interior, but also on whether it

has magnetic storms, auroras, and radiation belts - a practical concern for any

manned expedition to Venus. The magnetometer takes readings in space, too.

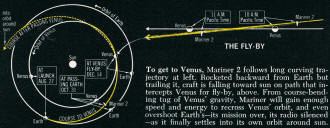

The Fly-By

To get to Venus, Mariner 2 follows long curving trajectory at

left. Rocketed backward from Earth but trailing it, craft is falling toward sun

on path that intercepts Venus for fly-by, above. From course-bending tug of Venus'

gravity, Mariner will gain enough speed and energy to recross Venus' orbit, and

even overshoot Earth's - its mission over, its radio silenced - as it finally settles

into its own orbit around sun.

Along the Way

As Mariner travels, still other instruments are measuring cosmic rays, the "solar

wind" of protons streaming from the sun, and the abundance of speeding micrometeors.

A crystal microphone counts pings of the meteors, like hail on a tin roof, against

an exposed magnesium plate. One of Mariner 2's first notable discoveries: Meteoric

particles are only 1/1,000 as numerous in deep space as near Earth - a happy augury

for space travel.

Mariner's progress toward Venus has been steadily watched from Earth by three

big radio telescopes. Spaced around the world at California, Australia, and South

Africa, they pass the task from one to another as the spinning earth brings each

into position. By teletype, their tracking data and reports from the spacecraft

stream into Mariner headquarters at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena.

At Goldstone, Calif., a tiny scientific community in a desert cupped by mountains,

are two 85-foot-diameter bowl antennas. One transmits commands to Mariner. The other

receives its reports.

To give Mariner a command - which may be either for execution at once or later

on signal - JPL sends a roll of pink perforated tape to Goldstone. An engineer there

presses a button, and the transmitting bowl flashes the message to Mariner. Thus

the spacecraft was successfully put through the most complicated maneuver any ever

performed - rolling and pitching into position, and briefly firing a tiny rocket

carried aboard - in a delicate midcourse correction assuring a bull's-eye on Venus.

Mariner itself is talking practically all the time. Over and over, it transmits

20 seconds of data from its instruments, then 17 seconds of "engineering" re-ports

about itself: its temperature inside and out, its solar panels' output of electricity,

and so on.

On sighting Venus, Mariner will switch off its engineering reports and devote

every second of the fly-by to transmitting observations of the planet-across 36,000,000

miles of space. So planned is the timing that Goldstone is the station due to receive

them.

Tom-Toms and Tape

The voice of Mariner, reporting from space, sounds like the beat of distant tom-toms.

But the eager listeners at Goldstone are not depending on their ears to transcribe

and preserve the priceless messages.

Mariner's drumlike signals are being recorded constantly on magnetic tape - five

miles of it daily. Most prized of all, if hopes are fulfilled, will be 800 precious

feet of tape, fruit of the 41-minute Venus fly-by.

At Pasadena, machines convert the magnetic-tape recordings successively into

perforations in paper tape, IBM cards, and, finally, long rows of numbers on paper

tape. As soon as scientists have had time to study and interpret these numbers,

the readings of the spacecraft's instruments, the world will know what Mariner has

discovered .

|