|

Using converted Volkswagen

engines to power boats, dune buggies, airplanes, water pumps, electricity generators,

fans, and other things was a popular meme in the 1960s. Hippies crashing their Bugs,

Beetles, and Vans while high on drugs made surplus engines readily available at

a good price ($250, per this article, which is about

$2,200 in 2023 money). The Evans Volksplane, which began appearing in full-size

aviation magazines sometime around 1968 or 1969, was very popular. I thought it

was in Popular Mechanics that I first saw it on the cover, back in the day, but

I cannot find it in a Google search. This "Flying Volkswagen," unlike the Volksplane,

looks pretty scary. It calls for piano hinges on the control surfaces, and I'm thinking

they were actual piano hardware rather than certified flightworthy gear. The $600

project cost in 1968 is the equivalent of around

$5,300 today, which is about what a fully equipped radio controlled turbine-powered

jet model costs.

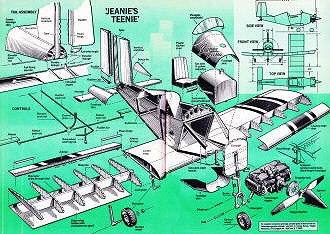

Build This 'Flying Volkswagen' for Less than $600!

Here's a remarkably easy-to-make, all-metal airplane you can

put together with simple tools and a minimum of experience. Full plans available.

Technical Art by Fred Wolff

By Kevin V. Brown

Just when the last breakthrough seems to be broken through someone else comes

along and does it again.

It's just happened in the field of amateur-built airplanes. A good general-average

minimum for homebuilts has been about $1000, and this for basically wood-and-fabric

aircraft. Now a new design, from the unlikely place of Daphne, Ala., boasts a maximum

cost of $600, and this for an all-metal airplane that a rank beginner can build.

Its major features are:

• A Volkswagen engine, the paragon of dependability and low cost.

• All-metal construction, and with over-the-counter parts and tools.

• Easy-to-build design, a one-man operation with no complicated equipment

or techniques.

• Easy-to-fly, not swift, but sporty.

All of this grew from the efforts and imagination of Calvin Parker, chief engineer

for a Mobile radio station. He lives near the station's tower at Daphne, and some

of the early construction and taxi tests were done around the tower.

PM's Aviation Editor pre-flights Jeanie's Teenie before test

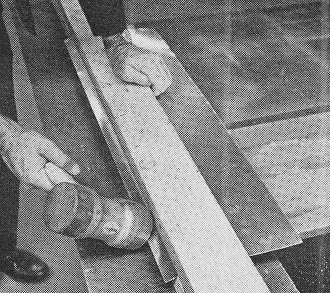

Simple Construction technique uses plastic hammer

to bend metal, eliminating jigs and brakes.

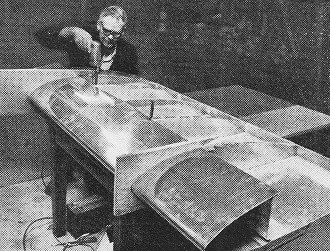

Calvin Parker drills rivet holes in leading

edge of wing, which is held in place by plywood template.

Volkswagen Engine was key around which plane

was designed. Tricycle gear uses three go-kart wheels.

Jeanie's Teenie has removable wings which can

be s towed in station wagon while the plane is towed.

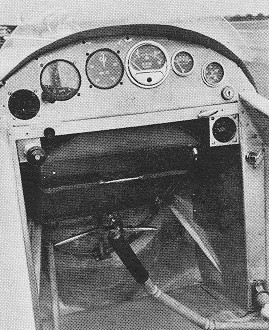

Simple Cockpit layout has basic instruments,

off. set stick, rudder bar and push rod. to control.

Lewis Long, original test pilot, tilts Teenie

up with one hand in a demonstration of its light weight.

Parker, who learned to fly in 1946, built a few airplanes from other men's designs,

but always felt there ought to be a simpler way to do it. While working for a large

West Coast aircraft manufacturer, he enlisted the aid - after working hours - of

office friends who were good with figures. He wanted to know what were the lightest

metals it was possible to use and still build a safe aircraft. When they'd run through

the figures and produced answers, he doubled everything and then began the design

of Jeanie's Teenie (for Jeanie, his daughter, who helped him with preliminary construction,

and Teenie for what it sounds like).

I visited Parker at his radio tower, and he told me how Jeanie's Teenie came

to be. Later I flew it.

"I designed it around the Volkswagen engine," he said, while showing me home

movies of the Teenie in action, "and I believe this is the first time it's ever

been done that way. A few homebuilts have been adapted to the VW, but I started

with the VW in mind. It's light, it's dependable and it's relatively inexpensive.

"Also, several available kits make it easily adaptable to airplane use."

The metal, as any amateur builder knows can be both a blessing and a curse. An

all-metal airplane, theoretically, should last forever, while a wood-and-fabric

job has a limited lifespan unless it receives exceptional care. However, metalworking

is not everyone's cup of tea. Complicated equipment and expensive tools are usually

necessary, plus some experience in learning to live with the idiosyncrasies of metal.

Parker solved most of these problems by designing his plane around metals that can

be easily purchased as stock items in any metal-products shop, and also can be cut

and shaped with tools as simple as a plastic-headed hammer and tin snips .

Most of the fuselage and wings, including the spars and bulkheads, for instance,

are built from standard 2024-T3 aluminum sheets, 0.020 and 0.040 inches thick. (The

thicknesses, incidentally, are double what Parker and his friends figured out years

ago as the minimum safe strengths for an airplane.) The push rods for the control

surfaces - one of Parker's major innovations, eliminating complicated pulleys and

cables - and various extrusions for strengthening and mating some of the parts are

also stock items.

A minimum amount of advanced workmanship is required. The landing gear and rudder

bar, for instance, need some welding, and the propeller hub and some of the extrusions

need machining, but these, Parker says, can be farmed out at minimum expense to

a local metalworking shop. For the rest, Parker demonstrated how most parts were

formed.

"I never used a jig or brake," he said, sliding a sheet of aluminum between 2

by 4s and tightening them with C-clamps.

About an inch-wide strip protruded, and he began hitting it softly with a plastic

hammer. "I just start at one end and go down the line. If you hit it too hard, it

will crack or rip, so you have to go over it easy about three times to bend it safely."

Larger bends, such as the leading edges of the wings or tail-assembly pieces,

were made simply by laying the pieces on the floor, bending them over and standing

on them. The wing ribs took special treatment. Cuts were made in the edges, because

the bends were going to be made around a curve. A template was made from plywood

to form the ribs, then the remainder of the plywood, which mated with the template

exactly, was used to lock the leading edge of the wing in place while riveted to

ribs and spar. "Pop" rivets, used throughout, eliminated more complicated conventional

riveting.

I went through an estimated cost list with Parker. Like most homebuilts, costs

vary with the individual's ability to scrounge parts, but here's an average:

Volkswagen engine ............. $250

Aluminum sheets and rods .... 200

Instruments, basic group ........ 50

Go-kart wheels ........................ 40

Special propeller ...................... 40

The biggest variance will be in the engine. Standard catalogs list rebuilt VW

engines of up to 40 hp from $160 to $400.

As for specifications, at the time of my visit, the Teenie had only 12 hours

on it, and a complete list was not available. But an estimated spec/performance

chart goes something like this:

IMAGE HERE

Parker claims the plane won't stall. He says it will sink fast, but with full

control. I never got a chance to find out. On the day of my test flight, conditions

were anything but ideal. Tornadoes had just passed through the area, and we had

a stiff crosswind with gusts and a 1000-foot ceiling.

Even so, I learned enough to spot the two major problems that Teenie builders

will encounter in the early flights. The VW engine, at best, is 40 hp, roughly half

what the smallest standard aircraft engine produces, although it's well mated with

the tiny Teenie. Even so there's not much margin for error. Also, because the plane

is so light, unless you're used to it - and I wasn't - it's extremely sensitive

on the controls. But most amateur builders would confirm this as characteristic

of all homebuilts.

On takeoff, to compound the problem, I didn't get the throttle all the way to

the firewall .. It's a lock throttle - I'm used to friction throttles - and it locked

about an inch from full power. Then, after I'd used about a third of the runway,

I tried to pull it off the ground and it leaped 10 feet in the air. I pushed the

nose down again, and porpoised violently a couple of times, before I got smart and

eased up on the controls. I passed the end of the runway before I noticed the throttle

gap. Once corrected, the plane climbed smoothly and the rest of the flight was routine.

I stayed within sight of the field to make my turns, and whatever climbs and

descents I could manage below 1000 feet, and found nothing unusual about any of

the Teenie's flight characteristics. It responds immediately, and with commendably

equal force, to all the controls, although Parker admits there was some trouble

adjusting the aileron linkage in the early flights to match them up. This suggests

each Teenie builder may have some small adjustments to make, too.

The open cockpit - my first - bothered me not at all, and I wasn't even wearing

goggles. Parker thinks the plane could pick up 20 mph with a canopy, but, even so,

it will never be a speedster, and some builders will prefer the sporty open-air

atmosphere. Helmet, goggles, silk scarf and all that!

So the only real advice Teenie builders need in building is to take special care.

Since the plane is almost entirely hand-made, you won't have special equipment to

compensate for sloppy work. A real premium will be placed on workmanship.

And the only real advice Teenie pilots need for the early flights is to use full

power on takeoff and ride easy on the controls. We estimated I was trying to struggle

into the air on 20 hp and making up the difference with muscle power.

Lewis Long, an Alabama school teacher, who helped build the first model, was

its first test pilot and now owns it, certainly had no trouble with it. He flew

it while I shot pictures (that's Long on the cover) and was rock steady on the controls

throughout, on takeoff, in the air and on landing. It just takes some getting used

to. And, if you're like me, you'll learn in a hurry.

In fact, if you're a low-time pilot, you might want to enlist the aid of a more

experienced pilot for the first flights to pick up any of your plane's individual

characteristics. Most amateur pilots are happy to oblige. It's an adventure.

A word here about the Federal Aviation Administration. An FAA inspector must

examine your plane before you can fly it. It's advisable to contact him early before

you get too far down the road. The first Teenie passed the FAA exam easily.

All in all, Jeanie's Teenie is a remarkable breakthrough in amateur construction.

It's not a Bonanza, nor even a $2000 homebuilt. But, at $600, if you build it conscientiously

and fly it intelligently, you'll get your money's worth.

Posted August 12, 2023

|