|

Up until the United States of

America officially entered what became known as World War II (on December 7,

1941, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor), what we now call World War I

was referred to only as "The War." Recall that is was dubbed by H.G. Wells

to be "The War to End

All Wars." It did not. This "Snapshots of the War" piece in the March 1937 issue

of Flying Aces magazine features what air power looked like in the early

days of World War II. Interestingly, the "cocarde" (aka "cockade")

referred to in the wrecked De Havilland D.H.-4 was, according to most

contemporary sources, a term used to describe similar insignia worn on military

head dresses and jackets. Insignia painted on military equipment was called a

"roundel." There is a very nice photo of a Clerget rotary engine as it was

mounted in the Sopwith Camel, along with the twin Vickers machine guns mounted

to fire through the propeller via synchronization with the engine. I have to

believe there were many instances of propeller getting shot off due to faulty

synchronizers, rounds that were slow to fire, or other reasons.

Snapshots of the War

Slow and solid - but sound. The old British Armstrong-Whitworth

(Ack-W, as the boys called her) was used mainly for camera and artillery observation

work, where speed wasn't so necessary. It mounted the old Sunbeam engine and saw

considerable service between '16 and '18. (Puglisi photo.)

Here's one of those Jerry (German) Albatross C-V's which attempted to

compete with the Bristol Fighters during '17. A splendid job, but not smart enough

to take the "Brisfit" on even terms. The Halberstadt later replaced the. C-V. (Puglisi

photo.)

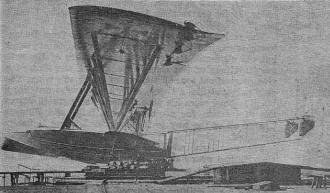

Another unusual "shot" - this time of a German Dornier flying

boat built late in 1915 for North Sea patrol work. Observe the structure of the

lower stub wing, a feature still used by the Dornier firm. And also note the steel

tubing used in the tail booms. The question is: "Where are the motors?" The propellers

are there, sure enough. Well, from what we can make out they were actuated by chain

gears running up from somewhere in the aft section of the hull. Anyhow, you might

sit down some night and try to figure it all out - which is probably just what the

Heinies did. (R. C. Hare photo.)

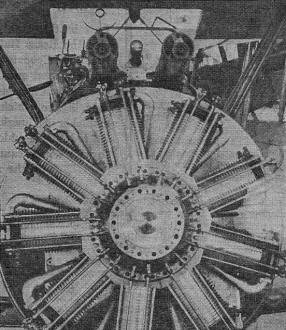

One of the best photographs we have ever offered on this page.

It shows in rare detail the Clerget rotary engine as it was mounted in the Sopwith

Camel. The cowling has been removed, of course. Note also the arrangement of the

two fixed Vickers machine guns, the nose of the Aldis telescopic sight, and the

ring sight. That small propeller fitted on the center-section strut to the left

ran a tiny generator which provided current: for the electrically-heated Sidcot

suits the British pilots wore in the last year of the War. A darned good picture,

and no mistake! (Williams Aerophoto.)

This crash must have got somebody on the carpet for a lot of

explaining. The D.H.4 shown at the left - that is, what's left of it - was being

stunted by an American airman over Trier aerodrome a short time after the Armistice

just when another Yank pilot was taking off in a captured German Fokker. In their

mutual excitement, they crashed together, and both fliers were seriously injured.

You wouldn't have cared to be mixed up in that mess, you say? Well, brother, neither

would we! Incidentally, that wasn't the only post-Armistice crack-up. Yep, the cocarde

on that upturned D.H. wing was the early form of American insignia.

|