|

During World War I, the

United States spent $1,500,000,000 on military aviation, resulting in the

development of various advanced aircraft designs. This 1937 issue of Flying

Aces magazine mentions a few of them. This was 19 years after the

armistice. Although these planes did not see combat due to the war ending sooner

than expected, they showcased American ingenuity and engineering prowess.

Notable examples include the L.W.F.G.2, which had a top speed of 130 mph and

carried seven guns; the Loening monoplane, which was the fastest two-seater

fighter at the time with a speed of 146 mph; and the Curtiss single-seater

fighter, capable of reaching 160 mph. These aircraft laid the foundation for

modern American military aviation, demonstrating that the significant investment

made during the war was not wasted.

Planes That Didn't Make It

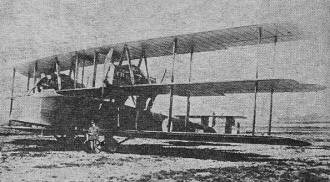

The British had their hard luck, too. This is the great Bristol

Braemer triplane bomber designed for long-distance raids on important German cities.

It had four Rolls Royce engines. The first of these was completed, and test-flown

a few days after the Armistice was signed. (Puglisi photo.)

By David Martin

Author of "Sky Gun Practice Today," "Modern M. G. Marvels," etc.

Our American aero designers "had the stuff" during the Great War - and don't

let anyone tell you different. Yes, the Yank experts had many smart craft besides

the Jennies to show for the $1,500,000,000 that was spent. And if the Big Scrap

had only lasted a few more months ...

In a recent report before a Senate Investigating Committee in Washington, General

Johnson Hagood testified that during the Great War the sum of $1,500,000,000 was

spent by the United States on military aviation. He went on to explain that no true

American planes ever flew on the front to justify this expenditure, except a few

"flying coffins." He was referring, of course, to the D.H.4, a machine that was

obsolete by the time America had entered the War.

Why this stigma was ever attached to the good old D.H.4 is something of a mystery;

for it compared favorably with every two-seat type of its time. The D.H.4, properly

built and fitted with a good engine, had a top speed of 120 m.p.h., landed at 52,

and climbed to 6,500 feet in eight minutes. It proved its worth on more than one

occasion.

The main fault with the D.H.4. was that the pilot and observer, with a massive

gas tank between them, were placed too far apart thereby cutting off all chance

of cooperation during action. This trouble was corrected later in the D.H.9 models,

hence the D.H. became one of the standard two-seaters of the war.

The trouble that followed with the American version of the D.H.4 was the insane

idea of putting the Liberty engine in the ship in place of the Rolls. It was the

Liberty engine with its unsuitable fuel feed that won for the D.H.4 that macabre

title, "the flaming coffin."

It's easy to set up a howl about how much money was spent for aviation during

the War and to point out how much we didn't get for it. But it is quite another

story to bring to light what we did get. General Johnson Hagood had a particular

idea in mind when he pointed out how little the $1,500,000,000 purchased in the

way of planes and engines. He was trying to disclose the complete lack of system

in purchasing and the failure to place the wisest heads in the positions of responsibility.

But what did this money purchase? What actually was gained by its expenditure?

Few know today; for the average war-time memory seems to become hazy when an attempt

is made to spotlight the obscure details that were so abruptly drowned out by ringing

bells and blowing whistles on that cold, cheerless day, November 11, 1918. Many

people figure that in the final analysis that $1,500,000,000 represented simply

a lot of men and materials-and let it go at that.

But that is by no means the full story-for if you look carefully in the right

places, you will find drawings, blueprints, and photographs of aircraft that would

amaze you even today-single seaters of tremendous speed and fighting power, two-seaters

that were far ahead of the famed Bristol Fighter, attack planes of a type never

known before, armored ships bristling with guns and yet hurling their unusual weight

through the air at racing speed, giant bombers, trim seaplanes, and powerful flying

boats.

One of the Liberty-powered, American-made D.H.'s. This particular ship was built

for the U.S. Government by the Boeing company. A few such D.H. jobs reached France

and actually went over the lines.

In other words, the War ended a few months too soon for the American designers.

Had the war lasted until the late spring of 1919, America would have been able to

place fleets of high speed single-seaters of real American type on the front. They

could have replaced the D.H.4s with fighting two-seaters the like of which had never

been seen. They could have bombed Berlin from Nancy. They could have out-armored

the much-advertised Junkers attack plane and they could have chased the Brandenburg

seaplanes all the way back to the Baltic.

Today, hidden away in great files or in the pages of war-time technical books,

we find the evidence of the real answer to the $1,500,000,000 riddle.

Here's Five That the War Forgot

$1,500,000,000 for U.S. Wartime Aviation was not all wasted. it provided planes

like these which turned out to be the basic designs on which to-day's great service

types have been built. But had the Great War lasted but a few more months - Whew!

Another Curtiss Fighter of 1918 - the 18-B, a two-seater using the 400 HP K-12

engine - This was a far better machine than the famed Bristol Fighter!

Curtiss Single Seater Fighter built late in 1918 - Used 400 HP Curtiss K-12 Engine

- believed to do 160 MPH with full military load

The Packard-LePere Fighter Speed 13G with 400 HP Liberty carried four guns

The Loening Fighter Monoplane - 1918 The fastest two-seater Fighter built during

the war - Top Speed 146 MPH with four guns, camera, oxygen tank, wireless and other

military equipment - It climed to 24,000 feet in 43 min. with a full load - This

was a Real Fighter

Many Years Before Its Time - The L.W. F Figther Biplane G2

This was an armored two-seater carrying seven machine guns. At a speed of 138

MPH it used the 350 HP Liberty Engine and could be quickly converted into a high-speed

Bomber carrying 600 lbs of bombs

The armor proecting the crew weighted 66 lbs. This model was built and test flown

late in the summer of 1918, but none got forward, the observer, three - The drawing

shows the two positions assumed by the observer.

For instance, did you know that there was an aviation firm at College Point,

New York, known as the L.W.F. Engineering Company? Well, sir, that outfit turned

out one of the most remarkable military machines in the history of the War. Known

as the L.W.F.G.2., it had a top speed of 130 m.p.h. fully loaded and carried seven

guns. It had a tail tunnel for firing under the body and to clear out the old two-seater

blind spot. The pilot had four guns all firing forward, and in addition the machine

could be used for bombing or reconnaissance work.

Outside of higher power engines and perhaps wing-flaps, what do the first line

machines of 1937 have over that?

An out-and-out American fighter that would have seen action had not the Armistice

nosed it out of the play. This 300-h.p. Thomas Morse Scout M.B.3 was so good that

it was kept on as standard equipment with our service until as late as 1918!

The plane carried 66 lbs, of armor plate around the pilot and observer, a point

which even our 1937 designers have not been interested enough to consider. We do

have parachutes, but consideration for the "odd slug" might be worth considering.

A chute doesn't do you much good after you're dead.

This machine, of course, was not built overnight. In fact, they turned out three

before they got what they wanted. First, there was the L.W.F. "G" type, which looked

more or less like other ships of that date. Then they designed the G-1 which to

our mind was distressingly worse. But they really went to work on her then, cutting

out the overhang on the top wing and taking the old Jenny effect away. They balanced

all the control surfaces and slapped in a wing-curve radiator. Mr. Whitehouse offers

you an idea of what she looked like in his accompanying cut-away illustration.

Then there was a Loening monoplane, perhaps the true forefather of American military

aviation - a craft to which many present day machines can trace their ancestry.

From a military standpoint this bus was probably the finest fighter of its type.

It had everything: speed, gun-power, and maneuverability. From the point of view

of gunner and pilot, her vision was tops. In performance she exceeded the speeds

of all two-seaters in the War. Her total weight was 2,368 lbs., and with the 300

h.p. Hispano Suiza engine she could do 146 m.p.h.

The pilot could see above and below the wings on both sides, and because of the

narrowness of the nose his forward vision was not materially hindered. The observer

could see all around and his two Lewis guns could be trained to fire forward as

well as all around him to the rear. He had only the arc of the prop to worry about.

The sides of the pilot's seat were covered with a transparent material enabling

both pilot and observer to see forward and downward. Broadly speaking, then, this

machine had no blind spots.

It is interesting to note that the Loening design of making the tail of the body

very narrow to give the gunner a better range of fire, is being touted today as

a modern idea in military design. The deep section forward enabled this ship to

carry a wide range of military equipment, including oxygen apparatus, cameras, and

two-way wireless equipment. The machine had a ceiling of 24,000 feet, so we can

understand why oxygen was considered.

The mystery to us is that no one today has considered taking this high-wing design,

putting in a 1,000 h.p. motor, adding slots and flaps, and showing the aviation

world where it gets off.

The Loening firm, which was located at 351 West 52nd Street, New York, in those

days, was also working on a small ship-plane. That was in 1918, remember.

Then there were the Curtiss products of that great year. Machines that, according

to photographs, compare very favorably with anything today.

Let's look at the deep-bodied single-seater fighter shown on the accompanying

drawing page. There was a real bus! It did about 160 using the K-12 Curtiss engine.

Yes, we agree it looks much like the Spad-Herbemont or the British Austin-Ball,

but it far out-performed them. It had clean lines and was well equipped for air

fighting of that day. We understand that it carried four synchronized guns and could

stay in the air well over three hours.

Another Curtiss machine that certainly out-performed the famed Bristol Fighter

was the Curtiss 18-B, a two-seater fighter in biplane form powered with the same

Curtiss engine. It did well over 140 and carried four guns and plenty of useful

military equipment. We can see the early trend in Curtiss fighters in these two

models - a trend which has carried through to many of the present day Curtiss military

machines. That's where some of the $1,500,000,000 went; and looking back we can

consider it money well spent!

Another Curtiss machine of interest was the Curtiss triplane. Yes, even Curtiss

had a crack at this type; and when they got through she hit 162, which was about

ten miles an hour faster than the famed Sopwith Snipe equipped with the A.B.C. radial

engine. Again in this triplane Curtiss used the K-12 engine which was rated at 400

h.p. She climbed to 15,000 feet in 10 minutes. We wonder now, incidentally, how

many pilots of that day were capable of handling a machine of this type. They also

built a single float seaplane in biplane form which probably topped the performance

of the triplane.

Other fine Curtiss types of that unforgettable year were the M.F. Flying Boat,

the Curtiss training sea-plane, the Curtiss R-8 bomber (which looked much like an

improved version of the D.H.4) and the great H-12 Flying Boat which used two 160

h.p. Curtiss engines.

In those days, they had their eyes on Berlin and a few will remember that even

then there was such a thing as the Marlin bomber. This was a twin-engined biplane

using, two 400 h.p. Liberty engines. The Martin "Twin," as it was known, was designed

for night bombing, slay bombing, long distance photography, or fighting. As a night

bomber, it was armed with three movable Lewis guns, one in the front turret, one

in the rear, and one set to fire under the concave body of the machine. She was

equipped to carry 1,500 pounds of bombs, 1,000 rounds of ammunition, a radio-telephone

set, and fuel for four and a half hours of flight. This was sufficient for a 600

mile raid at an altitude of 15,000 feet.

These are actual figures, not just conjecture.

As a day bomber, this job carried two extra Lewis guns, one extra on each upper

turret, and the bomb load was cut to half a ton. As a photography machine, the bombs

were replaced by two special cameras, one a short-focal length semi-automatic affair

and the other a long-focal length hand-operated machine. Later equipment included

a 37 m.m. semi-flexible cannon mounted in the front cockpit and firing forward with

a fairly wide range in elevation and azimuth.

So you see, aircraft cannons are not new.

A gentleman by the name of Donald Douglas was an aeronautical engineer with the

Martin plane in those days. Get it?

Even the most conservative British journals of the day stated that the Martin

bomber was far ahead of the field in design and performance. She did about 120 with

two engines and the ordinary wooden propeller. It was a biplane with the motors

set in nacelles between the wings. It had a span of 71 ft. 5 inches and an overall

length of 46 feet.

But they ended the war too soon for this craft, and so after a time they threw

off her military equipment and she became a prosaic old aerial transport.

The Packard Automobile Company, having a dabble in aviation in those days, designed

a splendid 160 h.p. motor. Then they decided to try building a war. plane, -and

they obtained the services of one Captain G. Le Pere, of the French Air Service,

who worked with them and produced the Packard-Le Pere fighter powered with the 400

h.p. Liberty engine. This Job was intended as a reconnaissance-fighter and carried

two machine guns firing forward and two Lewis guns in the rear cockpit. It had a

top speed of 136 and climbed to 6,000 feet in 5 minutes 35 seconds.

It was a biplane with box inter-plane struts and had what might be termed husky

design throughout. It looked very strong but not particularly fast. It was no doubt

intended for fast production for many of the most important parts seem to be interchangeable.

Thomas Morse, of Ithaca, N. Y., was likewise in the field - with many fine single-seat

fighters. The M.B.3, for instance, was still being used in many squadrons as recent

as 1928! Built late in 1918 - too late to see action - this craft used the 300 h.p.

Hispano Suiza engine, had a top speed of 164, and landed at 55. It was a biplane

of keen design and frankly had many of the features of the French Spad.

The grand old name of Vought was in the running even in those days - but then

it was Lewis and Vought of Long Island City. They turned out a neat training biplane

known as the V.E.7 which used a light Hisso.

There were many others, not forgetting the famous Boeing single-float seaplane

built for the Navy which used the 124 h.p. 4-cylinder Liberty and had a speed of

75 m.p.h. and an awful lot of wires. And Aeromarine built a splendid light training

biplane float-seaplane. But we could not close without a mention of the great N.C.

Navy boats which won the honor of being the first to cross the Atlantic. These were,

of course, Navy-Curtiss machines built to government specifications.

In reviewing all this, we can see much evidence of the basic designs now used

in American military aviation. The Loening monoplane had much to do with the monoplane

trend. The L.W.F. was probably the daddy of our attack ships. The first real effort

toward clean streamline design is to be found in practically all. So the $1,500,000,000

was not wholly wasted. We find neatness, compact detail, and snug precision so notable

in modern military ships.

Those ships may have failed to get in the War, but they certainly gave America

a sound basis from which to build up the three glorious services!

|