Table of Contents Table of Contents

The Boy Scouts of America has published Boys'

Life since January 1, 1911. I received it for a couple years in the late 1960s while in the

Scouts. I have begun buying copies on eBay to look for useful articles. As time permits, I will be glad

to scan articles for you. All copyrights (if any) are hereby acknowledged. Here are the

Boys' Life issues I have so far.

|

Once upon a time there was an

organization called the Boy Scouts of America, whose adult leadership sought to

prepare generations of young men to be brave, enterprising, purposeful,

resolute, enduring, partnering, assuring, reformed, enthusiastic, and devoted

(BE PREPARED) to himself, his community, and his country. Its membership was

exclusively biological male. The fact that I used the term "biological male" is

an indicator of what has gone tragically wrong with the BSA in the last decade

or so with wokeness and infiltration by ne're-do-well agents of change. Girls

are now admitted into Boy Scout troops, although they still have Girls Scouts

available. But, I digress. This aviation themed adventure article appeared in a

1938 issue of Boys' Life magazine, the official publication of the BSA.

Its arctic locale provided a challenging environment for pilots and air crews

since at the time many aeroplanes did not have enclosed cockpits. Imagine the

wind chill numbers while flying 80 mph in sub-zero degree weather. Impressively,

the characters discuss the Kennelly-Heaviside layer (aka ionosphere) and its

affects on radio waves.

Weather Hop

"Don't jump," Bob yelled, "I don't know whether we're over land or water!"

By Blaine and Dupont Miller

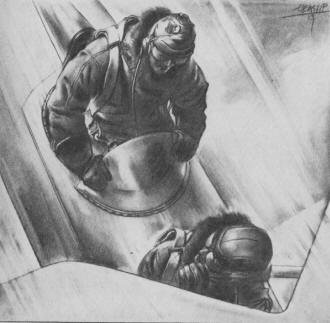

Illustrated by William Heaslip

A hard-packed, narrow runway lay rolled out in the knee-deep snow. From the top

of a radio mast swung a yellow windsock, blowing uncertainly in response to the

gusty winds which swept down the narrow valley. Approaching the field and flying

low was an Albatross airplane on skis bearing the insignia of the U. S. Navy. Leveling

off, it settled to the surface to slither to a stop before a tiny hangar.

Lieutenant Wakefield, the pilot, climbed stiffly and painfully from the cockpit

and stomped on the snow in an effort to restore his circulation. His assistant,

Happy Parker, followed him out of the plane and around to the aerological instruments

which were secured to the struts on the starboard wing. Bob opened the case and

removed a sheet of graph paper from a roller.

Examining it carefully, he said, "Fifteen thousand and a half, corrected altitude,

and all the recordings perfect. Guess that will hold old Ferguson for awhile!"

Happy smiled wryly, "It would hold him if he had to make these flights himself."

As Bob picked up the instrument case and started for the office, a figure in

a parka came out and hurried over to him. The flyer thought he detected a certain

sympathy in the mechanic's voice as Ajax saluted and reported to him, "This just

came for you, sir."

"Reports from Chignik Station inadequate. Necessary for plane to go higher in

accordance with existing instructions. Better communication essential. Greater co-operation

from unit desired.

"Ferguson"

Anger flooded through the pilot. Ferguson was riding him again! After the weeks

of arduous, dangerous, flights he and Happy had undertaken through williwaws and

pea-soup fogs! There had been only two clear days in which they had been enabled

to reach the required 18,000 feet. Ice had prevented every other attempt.

Didn't the man realize this was Alaska at its worst and they faced conditions

entirely out of their control? It was easy enough for him, sitting in a warm office

in Seattle to order the Chignik aerological unit to fly higher. All he needed was

a pencil and a despatch blank.

To the best of Bob's knowledge Ferguson had never done any flying. He was an

armchair executive; probably always had been, more or less. Bob didn't know him.

Had never seen him. But he knew his reputation. He was efficiency plus without any

judgment for latitude or circumstance.

"Bad news?" inquired Happy solicitously.

Bob returned to his surroundings with a start, "The same old thing, fellow. Ferguson

seems to think we're sitting up here crocheting bedspreads or something."

Happy shook his head. "I warned you what he was going to be like. That man is

such an efficiency fiend that he would regulate the snowfall at the North Pole to

suit his schedule, if he only could."

"Well, maybe he can arrange the weather, but I'd give a lot, Happy, if we had

some way of showing him that we can't do it. Ajax, service the plane and put her

away. 'We'll give it another try tomorrow."

In his office Bob thought back over the past month, When Captain Rumble had told

him he was to be detached for special duty while the U. S. S. Denver cruised further

to the westward, Bob had been delighted. The job sounded interesting. The Government

was making an extensive serological survey of coastal Alaska and it excited Bob

to realize that, through this work, it might be possible to forecast weather in

the United States a week ahead of time. What a tremendous difference such knowledge

would make to commercial airlines, to motor transportation, to farmers!

Only, at the end of his interview, Captain Rumble had informed him, "You will

be under the supervision of Commander Zebulon Ferguson. Zeb has the reputation for

being a mite difficult. He's ambitious and a great worker. But you use your own

judgment when it comes to flying. You can call on me if things get too thick, but

I don't think you will because you are capable of handling your own problems."

Bob's junior pilot, Happy Parker, had been more discouraging on the subject,

"So we're going to be taking orders form Ironman Ferguson! Bob, he's a holy terror!

He was instructing at the Naval Academy when I was there and he had the Plebes so

scared that you could hear their teeth chattering when he held an inspection."

"Maybe he's mellowed since then," suggested Boll hopefully.

But, this optimistic hope was soon dashed. When Bob had moved ashore at Chignik

with his unit and one of the Albatross planes mounted on skis instead of floats,

he had had no illusions about the type of work which was expected from them. It

would be both difficult and dangerous and he knew that his little group of seven

men would be isolated through most of the season. The attitude of Commander Ferguson

turned out to be an added hardship. Daily, he sputtered and fussed by means of radio

dispatches until this job, which Bob had undertaken with so much enthusiasm, was

rapidly becoming a nightmare.

Taking a compass course he soon brought the Albatross roaring in.

Now, Happy interrupted his reverie to ask, "Didn't Captain Rumble say something

about calling on him if you needed help?"

"Yes," admitted Bob, "but he also said that he was sure we'd be able to handle

our own problems. I hate to call on him except as a last resort."

Over in the corner, the Unit's radioman sat at a desk, his fingers lightly gripping

the vertical speed key. The "bug" beat out a staccato message.

"What's up, Ostrom?"

"It's that crazy set-up again, Mr. Wakefield. The Army station at Fairbanks was

trying to work Juneau and they couldn't get through. I was able to work both stations

so I relayed their traffic through."

"Skip distance again!"

"That's it!" agreed Ostrom, "Just the way it is sometimes between here and Seattle.

I know what it is, but I'm not exactly sure that I understand why it happens."

"I don't either," admitted Happy, "what is it, really, Bob?"

"It is nothing mysterious, but it is obnoxious, as you know from reading some

of Mr. Ferguson's messages. Happy, do you remember your theory enough to recall

the Kennelly-Heaviside layer?"

"That's the ionosphere, isn't it?"

"Right. It is the upper atmosphere between sixty and seven hundred miles high

which contains free electrons to such an extent that they bend the radio waves which

reach that altitude and return them to earth. Actually, you see, it is the thing

which makes the waves tend to parallel the earth's surface."

"But, it doesn't always do this?"

"No. The efficiency with which the waves are reflected back varies, depending

upon the radio frequency, the time of day, the season, and the geographical location.

Even sun spots cause a wide variation in radio reception."

Happy puzzled, "That must be why some places at great distances get good reception

while other places receive nothing, even though they may be closer to the transmitting

station?"

"Exactly. There's no known method of predicting the time or length of the performance,

either. Unfortunately, Alaska is particularly susceptible to this phenomenon."

"And that's why we can't work Seattle sometimes for several days in a row?" asked

the radioman.

"Correct," agreed the aviator, "Remember the other evening when, although you

were unable to raise Seattle, Cavite finally answered you and you cleared our traffic

through the Philippines? They cleared, of course, by way of Washington, who, in

turn, transmitted on to Seattle."

"Not exactly the shortest way," observed Ostrom. Talking calmly and impersonally

about radio had assuaged his fury, Bob found. A hot shower and a brisk rub down

calmed him still more and he decided definitely against appealing to Captain Rumble

for relief from his harassing situation. Somehow he would convince Commander Ferguson

that they were doing the best they could possibly do.

There were times, however, in the ensuing days, when Bob's resolution nearly

wavered. Maddeningly, it seemed to him that after he had ploughed up through the

thickest stuff, stretching his endurance to the breaking point, they would receive

the sharpest, most carping messages. Then, suddenly, there was complete silence

from Seattle. Had Ferguson been sent to another assignment? Had he finally seen

the light and begun to appreciate what the aerological unit was up against? Doggedly,

the Unit went ahead with its dangerous work - and wondered.

It was nearly two weeks later when Bob, flying down through the overcast below

him, headed for Chignik, saw a minesweeper painted the familiar battleship grey.

The Albatross swept low over the water and Bob read the name U. S. S. Seagull on

the stern. He rocked the wings from side to side as he pulled up in a vigorous zoom

and headed for the field. Landing, he broke the news eagerly. After two months of

solitude, the impending arrival created much excitement. It would mean newspapers,

magazines, possibly friends! Only Happy was quiet.

Bob asked him, "Do you have the same hunch that I have?"

Happy made a grimace, "If you are thinking that the Ironman is on the Seagull

-"

"Bull's eye!" exclaimed the Senior Aviator.

Happ looked at his watch, "It'll be just about dinner time when our visitor gets

ashore.

Suppose we kill the fatted calf? We've one more turkey and there's just enough

plum pudding to go around."

"Are you turning the other cheek, Happy?" asked Wakefield, with a smile, "You

know after that is gone we'll be down almost to hard tack."

"Well, if it is he, maybe the dinner will put him in a mellow mood and start

things off right."

Unfortunately, due to the fact that a recent storm had blown down their temporary

dock, Ferguson's arrival on Chignik Station was as miserable as possible. The Seagull

anchored some distance offshore and from there sent in a motor launch. The smaller

craft ventured in as far as the coxswain dared, which still left a strip of water,

waist deep, to negotiate.

In the bow, a slight figure swathed in a heavy overcoat and without boots, began

to call, lustily, "Wakefield! Wakefield! Get me ashore!" There was no question of

the man's agitation and annoyance. He was a querulous type.

It was Ajax who, sensing the situation, dashed in through the frigid water and

turned his back to the boat in order that the visitor could cling to his back. Then,

sloshing through the icy water, he carried his burden ashore. As the visitor was

set down he announced, "I'm Ferguson, Clumsy handling, my right foot is soaked,"

A crimson flush spread rapidly over Bob's face. Ferguson had a wet foot, did

he? How about Ajax who was standing on the outskirts of the group dripping from

the waist down? The aviator was furious as he struggled to control himself.

We can get you dry in the office, Mr. Ferguson," replied Bob, Then turning, he

said, "Hustle up, Ajax, and get into some dry clothes before your wet ones freeze

on you,"

Around the cherry-red stove, Ferguson told of the inconveniences of the trip

up from Seattle.

It had been most annoying. Rough seas and fog the entire voyage. Even the radio

went out for a day and they were unable to maintain communications.

"And then to top it all," added the visitor, with an annoyed frown, "You people

let your dock get washed away and I get wet coming ashore, You haven't much to do

up here, why don't you get your dock rebuilt?"

Happy looked at Bob as much as to say, "Get ahold of yourself, fellow!"

"We lost the dock only the night before last in that blow, and, of course, when

lumber has gone adrift up here there is none to replace it. We established this

station with very few supplies and the Denver had no spare lumber to leave here

for us."

Happy couldn't resist hinting, "Besides, if we had received any notice of your

coming, we could have put our outboard boat in commission."

Ferguson squinted cannily at Bob, "I don't believe in giving people warning of

an inspection young man. I want to see them as they actually are. In your case I

want to know the real reason why you don't go to the required altitudes every day,

and why, when you get data you often fail to get it through. Such a situation seems

absurd! We must take measures to correct it."

Bob was thoroughly discouraged. He had hoped that a visit to the Chignik Station

would produce a sympathetic point of view in the officer-in-charge of the project.

But, so far, there appeared to be little hope of that. The fog and storms through

which the Seagull had ploughed on her way north should have given Ferguson some

idea of the difficulties they were encountering daily. Surely, he realized that

the minesweep had experienced the same radio difficulty with which they had had

to contend-skip distance! But, there was no indication of a softened attitude.

Even the warmth of the stove and dry shoes failed to develop any signs of good

nature in the visitor. Ferguson held forth on the fact that serological planes throughout

the United States managed to reach the required altitudes and there was no apparent

reason why Bob couldn't. The fact that the Albatross was a stock service scout without

de-icers or cabin was ignored, Winter weather in Alaska was also ignored.

Bob looked at Happy, inwardly seething. It was a relief when the steward entered

to announce dinner.

"Atrocious meals aboard the Seagull and I must be careful of my diet," commented

Ferguson as they took their places at the mess table.

Conversation lagged over the valiant attempt at a salad which the steward had

provided. The guest picked at it gingerly.

"You don't care for salad, Mr. Ferguson?" inquired Bob.

The older officer raised his brows.

"You can hardly call it a salad when there isn't any lettuce, can you?"

"Well," offered Happy, "here's something that you are sure to like!"

In came the turkey, sizzling brown with ample supplies of sage dressing. When

the steward had set the fowl in front of Bob, the aviator began to carve.

"Frozen fowl, I suppose?" inquired Ferguson.

"Oh, yes! We just hang it outside the galley and it remains frozen," explained

Wakefield.

"So sorry. Frozen fowl doesn't agree with me."

By opening several cans, the steward managed to provide a satisfactory meal for

the inspector. Upon finishing the meal, Ferguson occupied the spare bunk and prepared

for a nap.

Alone in the office, Bob and Happy looked at each other.

"It was our last un canned meat!" protested Happy.

"I know. You must admit, however, that it was a bit tough. I wonder, though,

what he thinks we're living on during our stay here."

"Bob, let's get sensible. How long are you going to stand for this riding? You've

worked your head off and what do you get? Not even thanks. Ajax gets wet up to the

waist and what does he get? A growl. We break out the last of our Sunday dinners

and what do we get? A weak stomach! Let's get off a despatch to Captain Rumble."

"I have a better angle than that, Happy. Obviously, Ferguson didn't make a very

good sailor coming north. What kind of an aviator do you suppose he would make?"

Happy looked up quickly. Suddenly, his face was wreathed in smiles. Wakefield

winked.

Sometime later, just before darkness brought a close to the short day, the overhanging

fog suddenly swept clear to reveal the rugged outlines of the coast. This was the

phenomena for which Bob had prayed, a "false sunset" which they had every now and

then, giving promise of fair weather on the morrow. A promise which was never fulfilled.

Now, the low rays of the sun touched up the snow with a dazzling whiteness. It was

this brilliance which made Ferguson blink as he entered the hangar office, still

sleepy after his nap. He was forced to cover his eyes to protect them from the glare.

"The overcast has gone, Mr. Ferguson," greeted Bob, "looks like a good day for

a flight tomorrow."

The visiting officer glanced aloft. "No excuse for not going up to 18,000 feet

tomorrow, I suppose?"

"It looks now as though we wouldn't have an alibi tomorrow," agreed the senior

aviator. Then, he added, "It is possible that we don't understand exactly what it

is you want, Mr. Ferguson. I suggest that you come aloft with me in the morning.

No doubt, you could give me some new ideas on these flights."

The older man walked to the window. There was not a cloud in the sky. The wind

was from the north, and, in Seattle, would have assured a continuation of excellent

weather.

Ferguson cleared his throat, "That's why I came up here, Wakefield - to make

a flight with you and investigate these conditions about which you have been complaining.

I believe in making thorough investigations."

Before turning in that night Bob and Happy took a walk in the bright moonlight.

Happy smiled as he pointed to the halo surrounding the silver orb, "This'll be the

last night we'll see the moon for a long time," he predicted.

"The wind is already hauling around to the eastward," commented Bob.

They were correct. Dressing in the pitch darkness at seven in the morning, the

pilots glanced out to discover the normal scene. In the first faint light of the

dawn, they could see the low-lying clouds topping the hills to the westward. A five-hundred

foot ceiling. The stuff had pushed in solidly over them, abetted by the wind which

was now from the southwest.

By the time Mr. Ferguson had finished his breakfast Ajax had the Albatross out

of the hangar with the engine warmed up. The darkness began to give way to a light

grey, emphasizing more strongly the lowness of the overcast and thickness of the

fog.

The inspecting officer came to the door expecting to see the delightful view

he had witnessed the previous evening. There was nothing but an opaque grey blanket

which reduced vision and covered them with a layer of fog.

After a long pause, Ferguson said, "The Department of Commerce doesn't permit

a plane to fly unless it has a thousand-foot ceiling, does it?"

"That's contact flying, sir, and applies to the airways. We have no rules up

here except to go aloft every morning at this time and try to get through the overcast."

The inspector looked out toward the minesweeper. "You know," he said, "on second

thought, I have several things to do out on the Seagull and I think I had better

get them done this morning."

Happy looked at his senior aviator, despair in his eyes.

Bob picked up a winter flying suit which had been lying on the wing, He walked

up to the now miserable officer and, holding out the garment, he said, "This is

a good morning for Chignik, Mr. Ferguson. We've taken off in lower ceilings than

this. The flight will only require about an hour or so and I'm sure you'll be able

to help me out tremendously. Besides, you've come a long way up here and it would

be a shame to miss this opportunity of putting us on a more efficient footing."

Glancing at his watch, the aviator added, "We'll have to hurry, too, for Seattle

will be wanting our data shortly."

Ferguson muttered to himself as he climbed into the bulky coveralls. Perhaps

the flush on his face came from the extreme cold. So probably did his tendency to

tremble. But, whatever caused it, he was obviously a very unhappy man as Ajax secured

the safely belt around him.

The plane slid swiftly along the glazed snow and leaped into the air. Bob circled

low between the fog crested hills and headed out to sea, climbing at the required

rate of three hundred feet per minute. The overcast was entered just as the craft

started out over the water. This was just as well for no one enjoys looking down

lit water when in a landplane.

Glancing out at the instrument box, Bob was able to read the recordings of the

barometer. The steady climb registered as a straight line. Over the interphone,

he called, "Look at that temperature curve, Mr. Ferguson. First down and then up.

We seem to have a slight inversion today, but the needle will start dropping shortly

and she'll get really cold as we climb upstairs."

Up and up bored the plane. Now, well clear of land, Bob began a climbing spiral

to the left. They were in the midst of clouds. Nothing but moist greyness about

them. Under such conditions, the pilot became nearly automatic. Turn-and-bank indicator,

the compass, the airspeed meter, and the altimeter. His eyes roamed between all

these instruments. A bit of rudder, A little pressure back on the stick to hold

the machine in its steady climb. He disregarded his own sense of balance for he

knew it was not to be trusted when the horizon is obscured. Do only what the instruments

dictate.

Twenty minutes after the takeoff, Ferguson called, "Wakefield! Are you sure this

is safe?"

"No, I'm not sure of that, Mr. Ferguson, but this is the way we loaf up here

every day."

At ten thousand feet, the windshield began to frost over with a glaze of ice.

The pilot tried to wipe it clear with his gauntlets, but it was a wasted effort.

If anything, the frosty coating was becoming thicker.

Bob called, "If you'll look out at the struts, you'll see a grand accumulation

of ice, Mr. Ferguson."

"What will that do to us?" inquired the passenger in a tremulous voice.

"When we get so much the plane won't carry the load, we are apt to fall off into

a spin."

"Seems to me it is about time to return to the base, Wakefield."

"Oh, we can stay on awhile longer yet. We usually get a bit higher than this."

The pilot's fingers on the stick were numb in spite of his gloves, and his face

stung from the particles of sleet which pelted it like shot from time to time. He

knew how much worse it must be in the less-protected after cockpit.

All remained dark. The tell-tale halo of the sun failed to appear. They wouldn't

get above the stuff that day. The icing condition was getting worse. Bob looked

around for the first time. Ferguson's face was a mixture of fear and anguish. He

was holding tightly to he side of the cockpit. His eyes met those of the pilot.

"Go back to the base, Wakefield!"

"But, we've only gone to slightly over eleven thousand feet, Mr. Ferguson," protested

Bob.

"I don't care how high we've gone! I want to get down out of this machine. Pick

up the radio beam and return!"

"But we don't have radio beams in Alaska!"

It was then that the revolutions began to fall off. So slowly at first that the

pilot found himself opening the throttle slightly to hold the revolutions. There

was a low, blowing sound, as though the engine were starving for fuel. Then, all

was silent.

"What's wrong? What's wrong?" called the passenger, alarm in his voice.

The pilot was too busy to answer. He threw the nose of the craft sharply downward.

The weird whistle of the ice-distorted struts and wires was frightening. He leaned

the mixture in an effort to cause a backfire through the carburetor, the generally

accepted method of breaking the ice loose. But the carburetor throat was completely

blocked off by a mass of ice, so solid that even the heater failed to clear the

jam.

"What's wrong, Wakefield?" shouted the inspector, standing up in his cockpit.

"Don't jump," shouted the pilot, "I don't know whether we're over land or water.

Bob headed south to make certain of avoiding the mountains, even though this

would be placing them far from land. So intent was he in trying to clear the carburetor,

he failed to realize how tense he had become. His hand grasped the stick in an iron

grip. Perhaps this was to be the forced lauding they had always dreaded!

At two thousand feet the ice which coated the struts began to drop off in huge

lumps. A section at a time it would let go to ease the burden of the over-laden

plane.

"If we go in the drink, Mr. Ferguson, get clear of the plane and I'll break out

the life raft."

From the corner of his eye, Bob caught a glimpse of a grim, nerve-wracked face

peering into the opaque fog in response to the pilot's, "Let me know if you see

the water, Mr. Ferguson."

They broke through at six hundred feet. A quick glance revealed nothing but whitecaps

standing out against the dull slate-green sea. Bob had practically given up and

was at the point of devoting all his attention to the impending forced landing.

But there was time for just one more try. He had scarcely leaned the mixture when

the explosion of a backfire roared in their cars. Quickly closing the mixture, and

moving the throttle, the pilot once more found his engine giving forth power. Jerky

power, true, for the engine was cold. But, as it warmed up he was able to level

the plane off, and taking a compass course, he soon brought the Albatross to a halt

in front of the tiny hangar.

That afternoon, as Commander Ferguson stood on the edge of the beach, preparatory

to departing on the Seagull, he was a subdued, if not a somewhat pathetic figure,

in a pair of hip boots much too large for him which he had borrowed.

He cleared his throat and addressed Bob, who was standing beside him with Happy.

"In my report, I shall make clear that you and Mr. Parker have gone ahead with the

work in spite of tremendous odds against you. Tremendous odds!" he repeated, and

something, like a shudder went over his face, as if he remembered some of those

odds only too well.

He cleared his throat. "Of course," said he, somewhat apologetically, "I shall

be grateful for any weather reports that you are able to get through to us. Anything

at all will be appreciated."

Bob and Happy did not dare look at each other.

Ferguson took a few tentative steps out toward the launch, and then, over his

shoulder, sent a parting message, "I believe," said he, "that the Seagull has some

spare stores. I will send a quarter of beef ashore with the boots."

Alone, up in the office, Bob and Happy let out whoops of joy and suppressed merriment,

"We ought to celebrate," suggested Happy.

"We're going to celebrate!" promised Bob, "we're going to thaw that beef out.

Steak for all hands, tonight!"

|