|

Gold

Rush III is an R/C pylon racer that was ahead of its time -

and its competition - in 1962. Virtually none of the features of

the plane can be found in today's pylon racers, though, except maybe

the fiberglass fuselage. The homemade retractable landing gear (or

any type of retracts for that matter) is the most notable exception.

Full building instructions are featured on the plans. AMA rules

at the time called for a whopping 766 sq. in. of wing area with

a .19 size engine. If you are looking to build a vintage model that

probably flies pretty well both for speed and aerobatics characteristics

using a modern lightweight radio and much more powerful engine (or

electric motor), then the Gold Rush III would be worth considering.

Winning R/C Racer - "Gold Rush III"

Keith Storey of Pasadena, Calif., with his National Champ

radio control Pylon race plane; hez former AMA president.

|

"Gold Rush III" is a fun airplane to fly. It is really gentle and

sure on the controls, yet lively enough for pylon racing and it

goes where you point it. She seems to have few if any bad habits

- this pilot does though and the plane tends to forgive gracefully.

Don't let the "III" on the name fool you; this is not a series plane

developed through many years of "etc., etc." I just like the name

Gold Rush, and it seems to like me since we have been lucky together.

It was first pinned on a control line speed model back in '47, then

later used on my first scale-like R/C Bonzo in '57. Planning

and designing Gold Rush III was a lot of fun, too. I included several

things I have always wanted to try. I guess we have all dreamed

of a retracting gear that is strong and reliable enough for competition.

Secondly, I have been very interested in fiberglass for control

line fuselages in team racers and speed models. They worked well,

did not absorb fuel and weighed no more than a good balsa body.

I wondered what the results would be in a large R/C model. The first

step in these tests was to make one complete Astro Hog fuselage

in balsa and another of fiberglass. All-up weight of the 'glass

airframe was 10 ounces lighter! It was stronger in the problem areas

and much lighter yet still sufficiently strong in the tail section,

too. This fully monocoque fuselage gave almost one inch

more working area inside because it had no long motor mounts or

awkward bulkheads and stringers. Light weight 3/32" balsa at the

wing saddle and stabilizer gave all the rigidity necessary. Because

we used a female mold the exterior finish was mirror smooth and

we could incorporate extra details such as wing fillets and otherwise

difficult compound curves. The pre-cut and sanded engine mounts

were molded together with the skin so that it formed a very solid

unit. By this time we were getting pretty excited and so started

drawing lines for the Pylon Racer. Construction of Gold

Rush III with its fiberglass fuselage and retracting landing gear

proved to be more time consuming than planned. We missed the Dallas

Nationals in '60 by four days. But this was really an advantage

since it meant time for a thorough check. There were a few nutty

"bugs" too - like the landing gear escapement being mounted across

the fuselage with butt glue joints only. On the second flight the

gear came up just fine, but the flying gyrations loosened the glue

and the gear stayed up! Belly landing, here we come. We were quite

surprised ... she slid in smoothly. But you can bet that escapement

mounting was changed and quick!

Storey sez retracting gear is suitable for control line

use, too. Full size drawings for "Gold Rush" are on Hobby

Helpers' new Group Plan #362A. |

Speaking of belly landings, the ship has made three more since then

on dirt, grass and asphalt. I'll take the hard flat surface anytime.

The fuselage underside seems to be curved just right and the dihedral

sufficient so that the wing rubber bands take the worst of the shock.

I had tried to make it clean and smooth knowing that sooner or later

it was bound to come in wheels-up. Although Pylon Racing

is still a young event, several design requirements and compromises

have become evident. I would class them basically as speed-vs-maneuverability,

steady power plant, number of controls, easy ground handling, light

weight and strong construction and for my own pleasure I like a

touch of realism. Aim was to balance all these requirements in order

to obtain a consistent performer. No two approaches are exactly

the same which gives a variety of designs and styles on the line

and in the air. Starting at the top of the list, we have

all seen some very fast models that could not take advantage of

their speed because they could not fly straight and level and were

grasshoppers in the turns. Conversely, there are planes and pilots

that make perfect pylon patterns, but their speed is too low to

get into the winner's circle. So it appears we should have a combination

of each, and when compromise is necessary it would be best to shave

a little off the top of each. If there had to be a choice, I would

prefer sacrificing two or three miles per hour for finer, more accurate

control. For example, the ailerons on my first pylon racer were

adequate at high speed when all was well. But at less than full

speed, or in those tough unusual positions I seem to get into, the

control was too slow - much too slow. The ailerons on this new model

are much larger and have less travel for smoother response at all

speeds. These larger units could slow the airplane down a little

- this is theoretical, but even if they did it would be well worth

it.

This

more accurate control means a higher average speed on the course

as well as the "saving" factor described above. The faster your

model flies, the more critical it becomes and the more practice

it takes to fly a low tight pattern. Goofing a turn by going too

far or too slow or over-controlling can mean precious seconds on

your average speed. "S" curving down the straight-a-ways and jockeying

for a good turn position also slows your time. An airplane that

is quick, accurate and sure will save those seconds. Plain practice

with your present model using various control travel ratios can

be both pleasing and surprising. The ideas from just such experimenting

are in the Gold Rush III. This was really fun trial and error.

The engine-and-fuel combination will probably lend more

to consistency than any of the other factors, except for a pilot

who may sometimes get a little extra nervous. Just as in C/L speed

or team racing, a reliable engine is essential to achieve top performance.

The powerplant must operate the same or as nearly the same as possible

every time before we can practice racing, evaluate control response,

check efficiency of fuel and propellers, or make any changes for

improvement. I picked the McCoy 19 because it had the consistency

I needed for such practice. Using a crankcase pressure fuel system,

it developed the power to swing slightly larger props necessary

for a large wing area model. An AMA .19 size model must have 766

sq. in. of wing area, more than many stunt jobs with .45s in the

nose. For pressure use the Veco adapter with an .018" hole plus

a one inch long piece of 1/32" ID tube in the fuel line to give

non-surge running. Fuels that are too hot or too cold, just

as the "super hot" engines, can be a real problem. Those exotic

home-brew fuels have probably caused more no-flights or incomplete

flights than all other reasons combined. I have used Thimble Drome

Sport fuel (blue can) for practically all my flying. It is a good

medium range fuel for most weather conditions and will give the

Mac about 12,000 rpm on a 9" x 7" or 8 3/4" x 7" prop. That means

85-plus mph on a two-way average for straight flight as timed by

the FAST Club's FAI electric timers. There are many ways

to control a pylon racer. We have seen good planes with proportional,

relay and relayless equipment. The question is really how many control

surfaces must be moved to give accurate flight. Here again there

is no single answer. Match your equipment with the controls you

desire and are most comfortable with. Gold Rush III uses

an Orbit relay 6. It drives Duramites for elevator and a combined

aileron-rudder, and an escapement for elevator trim in conjunction

with the retracting gear. The relayless radios are much lighter

but were unavailable way back when. Mounting is simply gobs of sponge

and a couple of rubber bands shown in the profile view.

Combining aileron and rudder has become quite popular. Flight tests

have shown it is much easier and more consistent to use aileron

to roll an airplane on point smoothly and quickly to a 90 degree

position for your pylon turn. Rudder itself will drop the nose while

it banks the model and this can cause palpitations of the heart

- this action results in those grasshopper antics that can be rough

when two planes are in a turn at the same time. It costs nothing

to link them (CAR), and when combined the rudder area and travel

are both reduced. The results are smoother turns and better directional

control on the straightaways. You wouldn't really need rudder

at all if the takeoff wasn't part of the timed run. I have found

that if the wheels are hard rubber and placed between 15 and 17

degrees ahead of the actual CG, and your rudder travel is adequate,

you should be able to steer the plane just like a race car regardless

of the wind. This will also give you a lot of confidence when there

are two or more planes at the starting line. The escapement

on the fifth channel operates both landing gear mechanism and the

trim at the same time. There is a big change in the drag when that

gear comes up and I feel this elevator trim is essential. It is

a ground adjustable system and the fine threads on the IBM clevis

unit allows very accurate settings for hands-off flying.

The retractable landing gear does add to the speed of the Gold

J Rush, 4½ to 6 mph. The reduced drag helps keep a higher

speed through the turn and acceleration after the turn, as well

as take-off acceleration. Rubber bands do all the work of hauling

it up and extending it for landing. We chose rubber bands because

they are lighter than an electric motor, are very high in usable

power and provide a quick operation. If you are like me, you are

busy during take-off and don't want to let go of the controlling

switches for too long a time, so the faster you can retract the

gear, the safer it will be. I must admit I always get a

thrill when the gear snaps into the wheel wells and the plane goes

by looking almost real. This system should work equally well on

F/F and C/L models for that little extra performance or realism.

Our last two design items of light weight and strong construction

should be grouped together. Selecting the balsa wood for the wing

and tail carefully can mean a saving of four to eight ounces without

sacrificing strength. Silk the wing and paper cover the tail for

two or three more. All these little things do add up to higher performance

and less crash damage. The average Pylon Racer weighs about four

pounds, give or take a few ounces. This brings us to making

the fuselage and your question will be the same as mine. Does it

have to be fiberglass? No, it doesn't. But I can promise you more

strength and no additional weight, absolute settings for the wing

and tail, clean and easy to maintain, no fuel problems and corresponding

gain in weight, more room to work inside and ease of repair or very

fast construction of another one. It's fun, go ahead and give it

a try. If I still haven't sold you on the merits of fiberglass,

the plans do include ideas for a balsa fuselage. Cross section "C"

shows a view through the engine mount area with the bulkhead, double

sheet sides and Berkeley type 1/2 round planking for the compound

curves. Very light and strong bulkheads can be made by sandwiching

1/4" balsa sheet between two pieces of 1/32" plywood and cutting

to shape. Repeat this basic pattern on all cross sections except

"I". Remember the engine mount will be 1/8" less on the outside

or profile to fit into the smaller area. If you are eager

and ready to try fiberglass, look at cross sections "E" and "H".

These represent the balsa pieces used in the pattern from which

the mold is made. The fuselage will be in .two parts, a left and

right side. The 1/4" x 2" sheet balsa will hold all the formers

in true alignment. Those are 1/8" formers with 1/8" balsa sheet

as noted on the profile plan and the 1/2 round planking for the

curves. Each cross section should be repeated as "E" and "H". Set

these formers on the 1/4" sheet and lay up your form (pattern).

Sand it to the right size and don't be afraid to really put a finish

on the pattern. A thick filler or primer material will give quick

and good results. The better the finish on your pattern, the smoother

your completed airplane, so give it a little extra. Each

half of the fuselage should be glued onto a rigid 3/4" or 7/8" piece

of plywood that has also been well finished. The mold will be made

of a water base material such as casting plaster or preferably Hydrocal,

and we don't want any warps. Locate a dealer who handles casting

materials and obtain that Hydrocal if at all possible. Get his ideas

for a parting agent, too. He may have better ideas or newer products.

If not, a good cooking grease like Crisco should be spread evenly

over the pattern and the plywood. base. If you use Hydrocal,

mix as directed and apply a layer over the pattern and ply base.

Use some canvass or binder and build up the thickness to no more

than 1". Let the mix set up thoroughly before you remove your finished

mold. If everything went well, the inside surface should be just

perfect for the finished glass model. We will get into the lay-up

techniques, coloring and completion of your fiberglass fuselage

as well as the set up and check out of the landing gear in a subsequent

article.

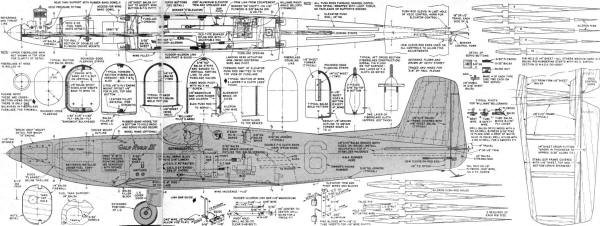

Gold Rush III Plans

(sheet 1)

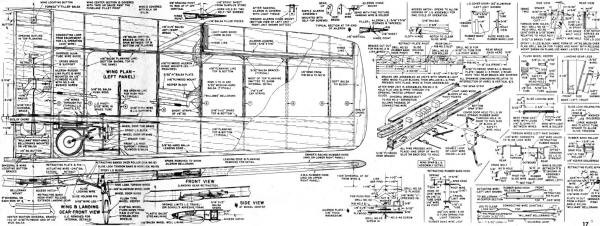

Gold Rush III Plans

(sheet 2)

Notice:

The AMA Plans Service offers a

full-size version of many of the plans show here at a very reasonable cost. They

will scale the plans any size for you. It is always best to buy printed plans because

my scanner versions often have distortions that can cause parts to fit poorly. Purchasing

plans also help to support the operation of the

Academy of Model Aeronautics - the #1

advocate for model aviation throughout the world. If the AMA no longer has this

plan on file, I will be glad to send you my higher resolution version.

Try my Scale Calculator for

Model Airplane Plans.

Posted November 28, 2013

|