|

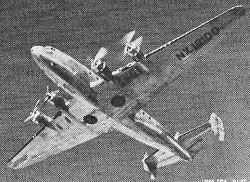

The Douglas Aircraft Company's

DC-4 conducted its maiden

flight on June 7, 1938. It was a hugely successful four-engined aircraft used for

civilian and military passenger and cargo transportation. Military versions of the

plane were designated

C-54 and

R5D. The DC−4 was designed to be

the airline industry's "dream" airplane - "a Grand Hotel with wings", capable of

cruise speeds of more than two hundred miles per hour and a range of 3,300 miles,

making it capable of non-stop coast-to-coast flight. Although the DC−4 was the brainchild

of United Airlines, a consortium of five companies - United, TWA, American, Eastern

and Pan American - financed the endeavor to ensure success would not be hampered

due to cost and competition concerns. The airplane's control systems were so complex

that a new crew member position called "flight engineer" was created to monitor

and tend to all the meters, dials, knobs, switches, and panel lights, while allowing

the pilots to worry mostly about flying. Although the DC−4 built on the overwhelming

success of its predecessor, the DC−3, such a large plane with twice as many engines,

tricycle landing gear, and many new creature comfort features required out-of-the

box thinking from the engineering team. The effort paid off big time, and earned

Douglas Aircraft Company kudos for a second paradigm-changing aircraft. I have always

wanted to build a control-line C−54, but I'm three years into a much simper

DC−3

now, so its likelihood is growing less by the day.

First of the Giants - Triple Tail DC-4

Twenty-five Years Ago United Air Lines Proposed

a Dream Plane. Douglas Built It. They Called It the DC-4. Doug Ingells Tells How

the 50,000-lb Triple-Tailed Giant Changed Air Travel. Twenty-five Years Ago United Air Lines Proposed

a Dream Plane. Douglas Built It. They Called It the DC-4. Doug Ingells Tells How

the 50,000-lb Triple-Tailed Giant Changed Air Travel.

Early in 1936, William A. "Pat" Patterson, President of United Air Lines, called

a meeting of operations and traffic personnel. The "Mainline" - pioneer transcontinental

carrier - was in a jam. United's fleet of 10-passenger Boeing 247 transports was

outclassed by the newer, larger, faster DC-3's used by American Airlines and Transcontinental &

Western Air (TWA). Something had to be done about it.

As an interim measure Patterson had ordered, DC-3 airliners, too. He had spent

more than $1,000,000 to "soup-up" the Boeings. But Patterson knew that United must

hit the competition with a Sunday punch.

"What do we want in an airplane?" Patterson asked the group. The result was a

composite dream plane: a four-engined luxury transport capable of carrying 40 or

more passengers, performability that would enable it to leap across the continent

with only one stop, speeds better than three-miles-a-minute!

Patterson took the broad concept to Commander Jerome C. Hunsaker; aerodynamic

expert at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for a basic airframe design, and

to the Pratt & Whitney engine people for powerplant potentialities. Before long,

he had detailed "specs" for the new sky giant. With these in his briefcase he made

the rounds of the various aircraft factories. Boeing was, too busy building big

flying boats. Consolidated Aircraft said the airline people didn't know how to design

airplanes. Sikorsky submitted a bid so low that Patterson's own directors ignored

it.

But at Douglas Aircraft Company in Santa Monica it was a different story. When

Don Douglas - whose DC-3 was acknowledged as the best airplane ever built - heard

about the proposal and learned his former boss at MIT, Jerry Hunsaker, was in on

the project, the Scotsman expressed keen interest. Douglas called in Chief Engineer

Art Raymond and they began to put some ideas down on paper.

The next time Douglas, Raymond and Patterson met, there was only one question.

Raymond put it to Patterson - "Engineering such a plane will take a lot of time

and a lot of money ... are you just looking or buying?"

"We'll put up $300,000 for the engineering cost, if you'll foot the bill for

the rest," Patterson told Douglas.

Douglas remembered his experience with the DC-1. The initial $125,000 TWA put

up was just a starter. He had lost money until they were well in the production

stages with the DC-2's. Then, it was the foreign business and additional airline

orders that finally took the company off the hook.

Twenty-five years ago United Air Lines proposed a dream plane.

Douglas built it. they called it the DC−4. Doug Ingells tells how the 50,000th Triple-Tailed

Giant changed air travel.

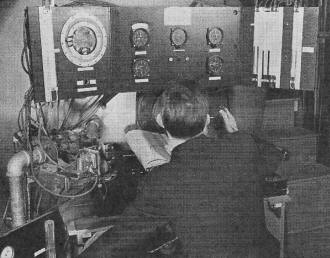

"Front office" of the DC-4 presented a complexity of instruments

that awed most pilots back in 1938. This mock-up was photographed in the Douglas

shops in that year.

A new term was "Flight Engineer," this was his station. The triple-tailed

transport pioneered the "third man" in the cockpit. Today he is standard part of

every big airliner.

Tackling such a giant project as Patterson was proposing could wipe out all the

gains and put the Douglas Company's prestige position on the block. Unless ... ?

Could Patterson guarantee enough orders so the risk would be minimized?

Patterson had an answer for that one. Other airlines - TWA, American, Eastern

and Pan American - had heard about the super airliner. They wanted "in" and all

had agreed to split the engineering cost with United. The "Big Five" had signed

a pact that none would spend any money with any other company in the design and

development of a plane in this weight category until they had first evaluated the

Douglas design. If the big ship proved up to expectations orders would follow.

It was almost like money in the bank. Douglas accepted the challenge. The DC-4

was born.

The super transport - roughly three times the size of the DC-3 - came to life

behind huge canvas curtains that screened off a section of the Santa Monica plant.

The magnitude of the task was de-scribed in a Company press release: "More than

500,000 hours in engineering and design, another 100,000 hours of ground and laboratory

tests, eighteen months to build. Some 20,000 different pieces of metal framed to

different shapes, 1,300,000 rivets. Total, cost - $992,808 for labor and engineering,

$641,804 in materials and overhead."

During the building of the DC-4 the plant took on a new appearance. Douglas,

himself, walking through the shops one day and looking up at the maze of scaffolding

around the jigs and forms for the huge wing made the remark, "That looks like a

part of a ship's superstructure, not an airplane wing spar. It's hard to believe."

Another time Douglas confided to Raymond, "I knew we could design planes as big

as this and bigger; but I frankly didn't know how we would ever build them!"

The size of the DC-4 posed a new problem with every progressive step. Take the

engine controls system. Each of the two outboard engines was seventy feet from the

cockpit. Yet, somebody had to work out a means that would permit the same positive,

sensitive response possible when power controls were only a few feet away from the

engines as in the DC-3.

"We had to start from scratch," recalls Ivar Shogran, Douglas' Chief of Powerplants.

"It meant designing a whole new controls system. But finally, we whipped it with

a combination of push-pull rods and cables that ran through the internal structure

of the thick wing. It was rather ingenious ... and it worked."

Shogran points out that they also had to devise a new fuel feed system, too.

"Each engine had a 100-gallon tank of special take-off fuel and another 300-gallon

tank of cruise fuel. You could switch from one tank to another with the flip of

the wrist. It gave the pilot extra power for take-off, the critical moment of any

flight. Yet, once the ship was airborne and set for cruise speeds she was ready

to start an economy run."

The engine control system and the new fuel-feed technique brought about a major

innovation in big aircraft design - the Flight Engineer's Station.

According to Douglas the problem was this: "We felt from the very beginning that

an airplane of this size was just too much for one man to handle. It seemed we were

asking that a pilot or co-pilot have four hands. So we built duplicate engine and

hydraulic system controls and installed a second control board just behind the pilots'

station. It meant putting a third flight crew member up front, but it took a great

load off the pilots during critical flight moments."

Another problem concerned the controlling surfaces. The DC-4's ailerons, rudder,

elevators were bigger than the wings on training planes Douglas was still building.

Only a Superman could be expected to move these huge "planes" in the man-made hurricanes

whipped up by the powerful propellers.

Solution? Control "boosters" were designed and applied. The standard control

cables were replaced with small diameter hydraulic lines. Small electric motors,

driving pumps, used the principle of the hydraulic automobile brake to operate ailerons,

rudder and elevators. In short; the DC-4 introduced finger tip control and "power

steering."

The matter of flight control plagued the aerodynamicists. Especially in determining

of the shape and size of the rudder. Bailey "Doc" Oswald, Chief Aerodynamicist,

reminisces, "It got to a point where we had blown up the DC-3 rudder to almost five

times its normal size and still we had instability. The normal rudder configuration

simply was no good."

He adds, "Then somebody, I don't know who it was, suggested we try three smaller

rudders and vertical stabilizers instead of one. The result gave the ship remarkable

stability especially during two-engine operation. And this was a must requirement

... that the plane be able to fly on any two engines."

(Later, they whipped the rudder problem and production models emerged with single

rudder configuration. But there was a triple-tailed DC-4!)

She was a giant. "It looks like somebody put a magnifying glass on the DC-3 and

made it three or four times its normal size." This was the comment Don Douglas heard

from one of the newsmen invited to see the roll-out of the plane in the spring of

1938.

These dimensions justified the remark: Wing span, 138 ft., 3 inches; Fuselage,

97 ft., 7 inches; Wing Thickness, 4 ft., 6 inches; Propellers, 14 ft. dia.; Weight,

65,000 pounds.

And she did look like an "overgrown DC-3." Even an official Douglas Company announcement

declared that the new all-metal sky leviathan's "design and construction follows

closely that of the DC-3."

At the same time Donald Douglas emphasized, "The DC-4 in no way replaces the

famous twenty-one passenger DC-3. Rather, it is an independent development anticipating

future needs for greater load capacity in trunkline operations for long distances.

It represents the Douglas Company's contribution to the science of aeronautics -

a new and significant milestone in aviation's progress."

The DC-4 was all of that and more. They called her "a Grand Hotel with wings!"

She could accommodate 42 guests by day and 30 by night. There was a Ladies' Lounge,

a Men's Dressing Room, a private compartment up front called the "Bridal Suite."

Comfortable seats arranged two abreast-twenty along each side - could be made up

into sleeping berths. Other features: air-conditioning, hot and cold water, electrically

operated kitchen or galley. There were also curling irons for the ladies, electric

shavers for the men and telephone service while the plane was in port or airborne

within radio contact range.

Virtually every improvement and innovation then available to the aircraft builder

was incorporated in the DC-4 - auto pilots, de-icers, controllable-pitch propellers,

a galaxy of instruments and navigational aids for the pilots. There were also features

which she pioneered.

The DC-4, for example, was the first craft of its size to incorporate the tricycle

landing gear. Instead of the familiar nose-up tail wheel and main landing gear (two

wheels) arrangement, the plane rested on two main wheels and a nose wheel. This

tricycle undercarriage meant that the big ship's fuselage was level when parked

on the ground, a boon to passengers.

More important, the tricycle gear greatly improved the plane's take-off and landing

characteristics. The airplane, in normal level flight attitude on the ground, presented

the control and lift surfaces to the airstream right from the beginning of its taxi

run - cutting out the need to "lift the tail high." In landing, the new arrangement

enabled pilots to literally "fly" the ship in, rather than let it settle with loss

of lift at the last minute. "Positive control right to touchdown," pilots said.

On the ground, they also claimed its taxiing capabilities far exceeded the maneuverability

of smaller planes because of the kiddi-car type undercarriage. You could turn the

giant on the proverbial dime.

Retracting the nose wheel and the big dual-wheels of the main gear was a major

mechanical problem. But the ship had "muscles" new to aircraft operation. Engineers

took advantage of two auxiliary motors working independently of its four powerful

Pratt & Whitney Hornet engines. The motors drove generators to provide electricity

and actuated pumps for the hydraulic controls that ran the unique "booster" system,

the auto pilot, landing gear, wing flaps and de-icers. They also drove the compressors

for cabin air conditioning and heating.

"We manufactured enough electrical current on board to light a large office building,"

Ivar Shogran pointed out. "It was the first time a generating plant of this size

had sprouted wings."

Patterson had gambled and won, too, when he took the powerplant problem to his

friend, Fred B. Rentschler, head of Pratt & Whitney. Rentschler had been itching

to get his new and powerful Hornet engines into a four-engined airliner and P&W

put everything into the powerplant for the "dream plane."

"The P&W gang at Hartford had made tremendous strides in engine improvement

without which we probably wouldn't have had the power available to get the 32-ton

airplane off the ground," Ivar Shogran emphasizes. "Higher compression ratios, supercharging,

tougher alloys permitting faster crankshaft speeds, redesigned fins for cooling,

did the trick."

The DC-4's 14-cylinder, twin-row, air-cooled radials totaled more than 5,600

horsepower - equal to the output of two diesel locomotives. The fact that Patterson

and Douglas and the others had taken the bold step to produce an airframe of this

size had spurred the engine people to produce the high horsepower engines. It was

the beginning of a new era in aircraft engine development. The DC-4 was the flying

testbed.

One thing was certain. There was plenty of power at his finger tips when veteran

Douglas test· pilot and Vice-President of Sales, Carl Cover, climbed into the pilot's

seat and took the new sky giant aloft on its maiden voyage.

It was June 7, 1938.

The plane came through with flying colors. When Cover landed he told Douglas-"She

flies herself ... I just went along for the ride!"

Early in the test program the Douglas Company released performance figures: Useful

load, 20,000 pounds; High speed, 240 miles per hour (faster than any bomber of that

period); Cruising altitude 22,900 feet; Absolute ceiling, 24,000 feet, almost five

miles above the earth; Maximum range, 2,200 miles.

Although the big plane flew in 1938, it was not until May the following year

that Douglas turned the DC-4 over to United Air Lines and the other participating

airlines for their flight evaluation tests. United, American, TWA, Eastern, Pan

American, in that order, assigned their own flight test crews to put the plane through

its paces.

Up and down the airways, east, west, north and south, landing at big metropolitan

cities and intermediate populated areas - wherever airports were able to accept

it-the plane made its public debut. Everywhere it went, people looked at the giant

with awe, almost disbelief that such a huge machine could lift itself into the sky

and hurtle through the air a such amazing speeds. Surely, this was the modern "magic

carpet."

Pilots liked it and praised it. Famous plane designer and racing pilot Benny

Howard ("Mister Mulligan") flew the plane for United. Howard really "wrung" it out.

At Cheyenne, Wyoming, elevation 6,200 feet, he roared down the runway in take-off,

reached up and cut out two engines. The plane soared aloft as though nothing had

happened. Watching this unprecedented demonstration of power reserve - and safety

- Jack Herlihy, Vice-President of Operations for United, beamed, "That's the airplane

for us!"

When Orville Wright, co-inventor of the airplane, walked through the ship during

a stop-over demonstration at Dayton, Ohio, the famous inventor told this reporter,

"This is more of a machine that it is an airplane, a giant complex machine of perfection.

It is a thing of mechanical miracles. Man doesn't fly anymore. The gadgets do all

the work."

Airline operations people were sure they had the answer to all their problems.

They were ready for the step into the true Air Age. The DC-4 had the range. She

could fly non-stop from San Francisco to Chicago, high above the treacherous Rocky

Mountains. Tons of radio, communications and navigational equipment aboard led her

across the limitless skies. She had the capacity to haul great loads, a crew of

five, two pilots, flight engineer, steward and stewardess, more than 40 passengers.

There was also plenty of room to spare for mail, express, baggage.

More important, perhaps, she could do all of this for about the same operational

cost per seat mile as the DC-3. Where cost did go up, increased performance and

capability made it almost negligible .

The results of the airline test programs brought about many recommendations for

improvements in passenger comfort and in design suggestions. The maintenance people,

for instance, wanted a single rudder configuration. Douglas had already worked this

out. The principal change, however, was from the passengers who wanted a pressurized

cabin. Douglas had already anticipated this and the pressurization system was "on

the boards."

There had been a split among the quintet of airlines who were underwriting the

DC-4 project. TWA and Pan American had "bought" the Boeing 307 "Stratoliners" -

first of the pressure-cabin passenger airliners. The Boeings weighed 1,000 pounds

under the weight restriction stipulated in the original agreement. Eastern also

pulled out. Unless they had a pressurized cabin airliner to compete with the Boeings,

United and American would be left holding the sack. They had to ante up the $300,000.

With that much money invested, Douglas wasn't going to let them down. He had

matched it and more. The DC-4 production model would have a pressurized cabin. American

and United placed orders for the new models.

A Japanese mission was in Santa Monica shopping around for a big plane to fly

their top brass from spot to spot in their so-called Co-Prosperity Sphere. The Japs

bought the original DC-4. On its initial flight with Japanese crews aboard the tripled-tailed

"Flying Hotel" plunged into Tokyo bay after take-off.

It had served its purpose well for Douglas. The plant was gearing up for production

of the modified DC-4 airliners, already they were being called DC-6's. The fact

is, Douglas really never built another DC-4. History had other ideas.

This was the year 1940, Great Britain was fighting for her life. France had fallen.

The Luftwaffe was relentlessly bombing Coventry, Birmingham, London and other English

cities. England, alone, stood between the U. S. and Hitler's dream of world conquest.

Britain needed bombers, not transport planes. On a visit to the Douglas plant

USAAF General "Hap" Arnold saw the work progressing on the modified DC-4 transports.

A few days later Douglas got a teletype directing him to stop work on the big transport

planes. United and American were asked to cancel their orders.

It riled the Scotsman's blood. He was already producing bombers for Britain faster

than the planes could be delivered across the Atlantic. It was his plant and if

he wanted a Board of Directors in the War Department that's where he would have

gone for them in the first place. Besides, Don Douglas believed there would be a

need in the coming war for a big plane to do an aerial logistics job.

"We're going to keep on building the DC-transport," Douglas told Raymond. "We'll

step up, the bombers and the other military ship production. But, we're going to

build the big one. They're going to need a big cargo plane before this war's over

and this is it."

Then something else happened. The Germans, with a great aerial armada invaded

the island of Crete. U. S. military observers returned with breathless reports of

giant gliders and huge four-engined transport planes that made the invasion lightning

swift and highly successful.

The teletype from Washington clacked out another urgent message - "Top priority

on the big transports."

Overnight, the Army air chiefs had concluded that the DC-4 was exactly what the

rapidly growing Air Force needed for global air transport. The DC-4 prototype became

the Douglas Skymaster. The Air Force called it the C-54. The Navy designated it

R-5D. It became the aerial workhorse of the war, carrying VIP's, troops, ammunition,

all kinds of cargo to the far four corners during the five years that followed.

After the war, many of the big cargo planes were converted into airliners and

they became DC-4's within the air transport industry. These rebuilt and refurbished

C-54's, all plushed up as interim airliners, carried the bulk of air traffic until

the DC-6's were ready. Then followed a long line of famous sky giants - the DC-6,

the DC-7, the DC-7C's, and finally the D-8 jets.

But they all owe their lineage to the first of the big ones - the tripled-tailed

DC-4.

Posted July 4, 2020

|