|

Here

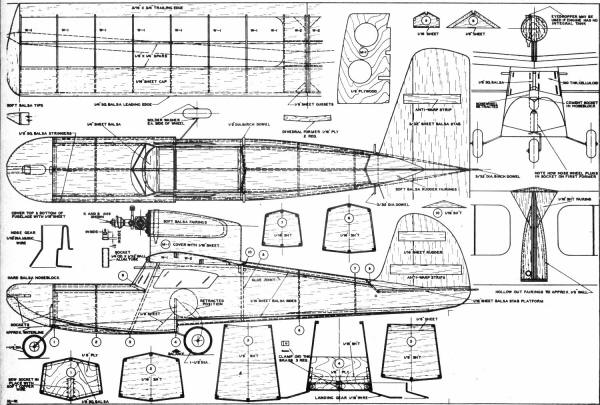

is a nice, quick project if you have ever wanted to try your hand

at an amphibious model airplane. The Shoehorn was originally designed

and built as an .049-powered free flight job with a 32" wingspan,

but with today's miniature radio systems it could easily be converted

to 3-channel operation. For that matter, you can substitute a brushless

electric motor for the glow fuel engine that, along with today's

high density, low weight Li-Po batteries, would easily provide as

much power as the .049. The Shoehorn is of built-up balsa construction

with Silkspan and dope covering, but of course there you could substitute

iron-on plastic covering available for park flyers (which this would

have been considered if park flyers had a name back then).

See all

Model Airplanes News items. Shoehorn Amphibious Model

Airplane

by H. A. Williamson

More apparent features include the lowest possible thrust

line for this type design, and trike gear - all wheels "retract"

for water operation. |

This is the time of year when fancy turns to hydro flying. And with

a classy boat like this Half-A to try, season gets started with

a splash. It's amphibious. Evidence of the growing popularity

of hydro flying was established this year with the inception of

several all ROW contests, that included Payload, radio control and

flying scale events, all run on the briny deep. Speedy runabouts

replaced the old familiar "chase cars." One of the contributing

factors in the sudden interest in ROW models is, undoubtedly, the

almost depleted source of suitable land flying sites, particularly

along the East Coast. Another factor, perhaps, may be the desire

on the part of many modelers to get away from the "Cut and dried"

classes and try some new and relatively unexplored fields. Admittedly,

there has always been a fair amount of interest in the free flight

ROW events, particularly at the Nationals. Unfortunately, these

models have seldom, if ever, in recent years, reflected any especially

noteworthy hydro design. In the main, they were, and are, tried

and proven pylon type ROG models quickly converted to this new medium

by the addition of several small floats. This is not to say that

the ROW contestants don't know what the score is: they certainly

do! The models are designed to give maximum performance under the

existing AMA rules and those guys who have the courage to fly a

red-hot pylon job off the wet handkerchief that passes as a tank

get my nomination for the Croix de Guerre! Flying a free

flight model off the water for sport is the particular phase we

are interested in, since it alone offers the opportunity to try

something new and unusual without being hampered by a stopwatch.

An amphibian such as the Shoehorn is an example of a model

of this type. It will never win an ROW free flight contest. It probably

couldn't get off the water in the tanks usually provided at contests.

This ship was designed to give semi-realistic flight and hydro characteristics

and is built ruggedly enough to withstand more than a normal amount

of abuse. If you're in the market for something a little

different, this may be just the job for you. Even if you don't live

within miles of a sizable body of water, or can't swim, the Shoehorn

is a nice performer flown as a conventional sport job with the gear

down and locked. Several features of this little ship are perhaps

interesting enough to mention before we get into the construction

details. The fuselage or hull design is the conventional

and very popular sheet balsa type with 1/8 in. square balsa stringers

at the intersection of the sides, top and bottom. In addition to

an appreciable increase in structural strength, it also reduces

the hazard of a cemented joint popping open and thereby allowing

water to enter the hull with possibly serious consequences.

Lower engine mounting and fairly wide hull enables ship

to get off water without help of troublesome sponsoons or

tip floats. Weight is 8 ounces.

Classy little wagon, we'd say! Hull is given three coats

dope, covered, then three top coats - also three coats inside

cabin. Green and yellow. |

When we just "doodled" the design on a piece of scrap paper, it

was decided that a "trike" gear would be the thing to have, never

giving a thought at the moment to the feasibility of making it work.

After one heck of a lot of head scratching and lost slumber we hit

upon the arrangement shown on the plans. The nose gear (the real

fly in the design ointment) is formed like a bobby pin and pressed

into an aluminum tubing socket that is sewn to the first former.

The main gear is held on the face of the step by three small clamps

and No. 2 wood screws. In this position the ship is rigged out for

land flying. To convert to ROW operation, the nose gear is slipped

out of the aforementioned socket and inserted in the socket shown

in the nose block. The screws in the side clamps of the main gear

are removed and the gear is rotated into the retracted position

shown on the plans. The two small holes in the step can be plugged

by replacing the screws and the main gear is held in the retracted

position with a rubber band. This arrangement overcomes the problem

of severe center of gravity changes when converting from ROG to

ROW and vice versa. The hull is somewhat wider and more

spoon-billed than is normal for a model. This was done in a conscious

effort to eliminate troublesome tip floats or sponsoons. So far,

the idea seems practical, if care is exercised in ROW take-offs.

To increase further the hydro stability, the engine nacelle height

was kept to an absolute minimum, providing only sufficient clearance

for a 6 in. diameter, prop and thereby lowering the CG.

Whether or not the hull design is hydrodynamically efficient is

debatable. A yacht designer friend says it could be improved and

without doubt this is correct. The fact remains, however, that it

works and provides loads of flying fun. The Shoehorn is

designed for .049 to .065 engines. Total weight, ready to fly, should

be approximately 8 oz. Wing span is 32 in.; wing area, 165 sq. in.

The original model is covered with light green tissue, with

yellow trim and black pin striping. So much for the preliminaries.

Let's get on with the main event - building your version of the

Shoehorn. Cut out the sides from medium hard 1/16 in. sheet

balsa. Notice where the sheets are joined together to get the proper

width. Trace the outline of each of the formers on the proper type

of material as indicated on the plans. Cut the formers carefully

and accurately to size.

Mark

the location of bulkheads No.'s 3 and 5 on each of sides and begin

assembly by cementing them in place, paying careful attention to

proper alignment of the sides. After the cement has dried, begin

with former No. 1 and cement the rest of the formers in place.

The 1/8 in. square medium hard balsa stringers are slipped

into the notches in the formers and securely cemented in place.

Sand the corners of the stringers off to fair them in with the slope

of the sides. The top and bottom of the hull or fuselage are cut

from 1/16 thick quarter-ground sheet and carefully cemented to each

former and jointed together along the center stringers.

Cut the stab platform from 1/16 in. sheet and slip it between the

sides and cement in place. The windshield fairing is cut

from 1/4 in. hard sheet balsa and cemented to the front of former

No.3. Trace the nose block side and top outline on a medium

hard balsa block and roughly carve to shape. Spot cement the block

to former No. 1 and carefully carve and sand the block to fair with

the fuselage lines. Pay careful attention to the sweep of the bottom

lines as shown in the side and front views on the plans. The entire

fuselage should be sanded at this point in the construction. Be

careful not to round off the chines (junction of the bottom and

sides); keep it sharp as shown in the former details. Make

up two aluminum sockets from 1/4 OD x 1/32 tubing as shown in detail

by carefully squeezing in a vise. One socket is wired and cemented

to former No. 1 and the other is inserted in the front of the nose

block. Then replace the nose block, cementing it permanently in

place. The nose gear and main gear are bent to shape from

1/16 dia. steel music wire following carefully the outlines shown

on the drawings. Place wheels of the proper size on the gear and

retain by soldering small brass washers to the wire. Make three

small clamps from .010 thick sheet brass by forming it around a

piece of 1/16 wire and squeezing it flat with a pair of pliers.

The main gear is held in place as previously mentioned with three

No. 2 x 3/16 round head brass wood screws. For maximum strength

and watertightness, the fuselage should be given at least three

coasts of clear dope and a final sanding before covering with tissue

or lightweight Silkspan. The covering material should overlap about

1/8 in. at the chines and at the junction of the sides and top.

For maximum strength and toughness the nose block may be covered

with silk or nylon. After covering, the fuselage should get three

coats of clear dope outside and also in the cabin area. The original

was covered with dyed tissue, eliminating the necessity for colored

dope and keeping the weight down to a reasonable figure.

To finish the fuselage, the wing and stab hold-down dowels are

placed as shown and the .010 thick celluloid windshield and windows

cemented in place. The basic wing construction is undoubtedly

"old hat" to all, so we will refrain from any tedious step-by-step

procedure. Instead, let's talk a little about some of the points

that are a little out of the ordinary. Note, during construction

of the wing, that a 1/8 in. space is left between the W-2 ribs to

accommodate the 1/8 in. thick plywood engine nacelle keel. This

unit should fit snugly between these ribs after the leading edge

and center panel have been covered with 1/16 in. soft sheet and

the dihedral formers are in place. Care should be taken during construction

of the wing to align ribs W-2 squarely with the leading and trailing

edges to insure proper alignment of the engine. The sides

of the engine nacelle keel are covered with 1/16 sheet balsa after

it is assembled to the wing. Cheeks, carved and sanded from soft

balsa blocks, plus the 1/8 in. ply firewall are cemented to the

nacelle as shown. The firewall should be drilled for the particular

engine used and may be mounted with small wood screws. If your engine

does not have an integral gas tank, an eyedropper, located as shown,

may be utilized. Some 1/16 in. thick sheet balsa is used

to construct the fairing from the top of the fuselage to the wing

center panel. The wing should be aligned properly and pinned to

the top of the fuselage to insure accuracy between the face of the

fairing and the fuselage. The entire wing assembly should be covered

with dyed tissue or lightweight Silkspan. Six coats of clear dope

will insure a watertight covering job and reduce the weight of the

ship in the long run by reducing the amount of moisture the frame

work will absorb. The rudder and stab are of the simplest

design. The rudder is made of 1/16 thick medium hard sheet, while

the stab is cut from medium hard 3/32 thick balsa. Anti-warp strips,

accurately cut from sheet, are carefully fitted in slots cut in

the rudder and stab as shown and carefully cemented in place. Soft

balsa fairing blocks are cemented to the rudder and stab and carefully

carved and sanded to blend in with the fuselage. In addition to

improving the appearance, these blocks add materially to the strength

of the cemented joint between stab and rudder. The empennage

group, like the rest of the ship, should be covered with tissue

or span and given two coats of very thin dope. The finished

ship should balance on, or very near, the front spar, as shown on

the plans. Any wide variations from this point should be compensated

for by the addition of weight to the nose - or tail, whichever is

required. Carefully sight along the wing and tail surface for any

signs of warping. Any that may be present should be steamed or doped

out before going any farther. Flight testing, to be on the

safe side, should begin by hand gliding into a patch of soft grass.

Adjust wing and stab incidence angles to obtain a smooth straight

glide with just a trace of stall. First power flights, as with glide

tests, should be attempted over land. Initial attempts should be

made with, reduced power, gradually increasing the throttle settings

until full power is attained. Power flight path should be almost

perfectly straight, with a smooth, steady climb. Offset engine thrust

line as required to remove all traces of power turn. At

this point in the flight testing, a little left turn should be added

to the glide path, but not enough to affect powered flight, to keep

the Shoehorn within walking or swimming distance. After the ship

is flying satisfactorily over terra firma, the initial water flights

can be made. The gear should be retracted for all ROW flying

and the ship hand-glided several times to make certain the balance

point has not changed. ROW take-offs require a great deal

of practice and patience but are well worth the effort. If your

Shoehorn has been adjusted properly over land, no trouble should

be experienced on the bounding main. You haven't lived until

you've spent a warm Sunday afternoon flying a hydro job. Try it

and see!

Shoehorn Amphibious Model Airplane Plans

Notice:

The AMA Plans Service offers a

full-size version of many of the plans show here at a very reasonable cost. They

will scale the plans any size for you. It is always best to buy printed plans because

my scanner versions often have distortions that can cause parts to fit poorly. Purchasing

plans also help to support the operation of the

Academy of Model Aeronautics - the #1

advocate for model aviation throughout the world. If the AMA no longer has this

plan on file, I will be glad to send you my higher resolution version.

Try my Scale Calculator for

Model Airplane Plans.

Posted March 9, 2014

|