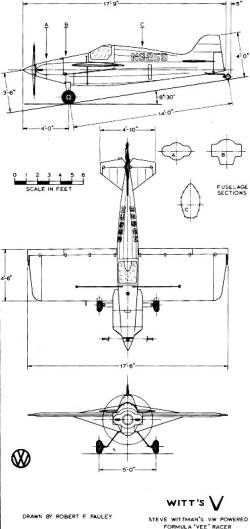

|

Steve Wittman,

aka "The Grand Old Man of Air Racing," was a prolific airplane designer, builder,

and pilot. His Wittman Tailwind homebuilt airplane was very popular and proved to

be fast and efficient for its size and power. The "Formula Vee" racer, motivated

by a highly modified Volkswagen engine, easily broke the 170 mph speed benchmark.

Making outside-of-the-box tradeoffs like suffering the drag of wing bracing wires for

a lighter and thinner airfoil are what made Wittman a crafty - and winning - designer.

A scale model of the Wittman Vee might benefit from a slightly thicker airfoil and

larger tail surfaces unless you want to have to aggressively fly the craft the entire

time it is in the air. This article and 3-view of Witt's Vee appeared in a

1974 issue of American Aircraft Modeler magazine.

200 MPH Volkswagen?

The Grand Old Man of Air Racing, Steve Wittman, looks forward

to his 70th birthday and to his first race in his Formula Vee racer.

"Witt's V," like all his other racers, is faster than it looks. The simple

lines are very efficient.

by Don Berliner and Bob Pauley

Some people just don't know when to quit. Like, for instance, Steve Wittman.

In the Spring of 1974, he'll be 70 years old. That's the time to sit back and

reflect on more than 40 glorious years of designing and building and flying some

of the most exciting airplanes the world has ever seen; and on a lifetime of showing

the aviation world that there's a simpler, cheaper way of doing what other people

insist on doing in complicated, expensive ways. The spring-steel landing gear on

the past 25 years' worth of fixed-gear Cessnas is one of Steve's clever inventions.

And a 125 hp two-place lightplane that cruises 50 percent faster than anything the

industry has been able to create? Well, his Tailwind does that with ease.

Steve has had more harrowing experiences than most people can imagine. Like the

time he was shot down while flying over the Great Smokey Mountains and came out

of it without a scratch. Or like the time, many years ago, when his engine quit

during a race and he landed on top of an Army bomber! Or the time he threw a prop

blade while flying out over the middle of Lake Michigan in his Tailwind-and glided

back to his home field to land with an ice-cold engine.

Even that sampling would be enough for anyone person, no matter how talented.

But small, fast airplanes have been so much a part of Steve

The shortest route to speed is aerodynamic cleanliness. Witt's

Vee has no more than the absolute minimum frontal area and a very thin wing.

The Instrument panel of Witt's Vee: Simple and lightweight. (From

Left): Manifold pressure, oil pressure, G-meter, airspeed, altitude, oil temperature.

The critical area where the wing meets the fuselage. The square-sided

cowling is easier to build and just as clean as one with flowing lines.

Landing gear struts are of titanium. Wheel pants will come later.

Classic Wittman lines: Boxy. with a strange combination of curves

and points. But it's the first one across the finish line that wins ... not the

prettiest.

A long prop extension permits the sharpest nose of any VW-powered

engine.

Wittman's life, that neither age nor retirement could interrupt their romance.

In fact, the extra spare time afforded by retirement was just what Steve needed

to enable him to start on some of the projects he'd been thinking about for years.

Priority Number One went to a Volkswagen-powered sport racer for the new Formula

Vee racing class. The idea of building an airplane suited not only for racing, but

also for low-cost sport flying really appealed to Steve. And using a car engine

in a homebuilt airplane was another idea with all sorts of potential, especially

in view of the steadily rising cost of the few small aircraft engines still available.

Steve had been in on the beginnings of Formula Vee, back in March of 1964. The

men planning an "aerial Olympics" for Palm Springs, Caif., wanted a new class of

homebuilt racers, and so Formula Vee was created (it was then the 95 cu. in. class)

from an idea then being worked on in England. The Palm Springs extravaganza was

pretty much of a flop. Formula Vee was more so. There wasn't a single airplane off

the drawing board, let alone in the air.

As the 1960s dragged on, sport racing type people went in the direction of the

established Sport Biplane Class and Formula I. These classes were growing well,

but not so well that a lot of people and money could be siphoned off to start a

new class without risking serious damage to the old ones. Formula Vee just sat there,

whimpering.

Finally. in 1969, the first pieces of metal were cut. And even though there was

no immediate prospect of a race, Steve's V out for public view during the first

EAA Fly-In to be held at Wittman Field, Oshkosh, Wisconsin. The 1970 Fly-In was

held at the field he had managed from 1930 until the late 60s; his home and hangar/shop

are just across the runway.

The airplane so eagerly awaited by homebuilders and race fans alike must have

been something of a disappointment. It was an oversized Formula I: angular, hump-backed

and painted a garish green with yellow wings. It wasn't particularly sleek. It certainly

wasn't very pretty. And it didn't look very fast.

But it was by Wittman. His Tailwind fits the above description more or less,

and it's darned fast. Sporting aviation people have long since learned not to scoff

at anything from the wise old hands of Steve Wittman, and so they looked very carefully.

What they saw was the shape of things to come-just like his Buster had shown

them in the first Formula I race at Cleveland in 1947. For the first decade of Midget

Racing, practically everyone who had started off in some other direction, eventually

came around to Wittman's way of doing things. That was because Steve's homely little

racers won most of the races in those days.

He won races because his airplanes were clean and light and simple. They got

off fast and they got around the turns with a minimum loss of speed, and they rarely

failed to finish a race due to mechanical problems. This philosophy has worked for

Wittman for many years, and he sees no reason to change it. The new little VW machine

was simply more of the same.

With an empty weight of 435 lb., and the required minimum wing area of 75 sq.

ft., he came up with a wing loading, at racing weight, of about 8 lb. per sq. ft.

This means such tight pylon turns that not even the most nimble of Formula Is could

hope to keep up with him around the turns. Several tried it in an exhibition race

and watched him leave them flat at the corners.

One way he kept the weight down was to use thin wires to brace the wing, so he

could get by with a much lighter wing spar (and faster airfoil) than airplanes having

cantilever wings. A bonus advantage of this is the elimination of the spar sticking

through the cockpit - any extra room for the pilot can be a blessing on cross-country

flights.

One of the big problems with VW-powered airplanes has been the high drag of the

blunt nose, for the famous German car engine is not meant to be tucked into a streamlined

airplane cowling. Steve turned the engine around (so it runs the right way and he

can use standard propellers), and built a special housing for a long extension prop

shaft. With the widest part of the engine far behind the prop, a super-sleek cowl

could then be built.

Construction is basically conventional. The wings are of spruce with plywood

covering. The fuselage and tail are built up of chrome-molybdenum steel tubing and

covered with fabric. Only the landing gear is different, with all struts having

been machined from titanium stock-light but rather springy.

Even after the airplane flew in late 1970, development moved slowly, for there

were no other Formula Vees in the air, hence no races coming up. Steve wasn't satisfied

with the center of gravity of his little bird, and made a major change in the location

of the wing. The engine, too, gave problems. for he was exploring unknown territory

in the use of a VW engine in a high performance airplane. Prior to his racer, VW-powered

lightplanes had been operating in the 100-130 mph range. He passed by this without

a pause. and then 150 mph, and then 170 mph.

As he slowly built up hours on his new No. I, he became more and more pleased

with its handling characteristics and speed range, and this was what he wanted.

Soon, spectators at fly-ins and airshows were witnessing aerobatics displays by

Wittman and his little Vee:

Rolls on top of loops, snap rolls, and even the rarely seen falling leaf. From

a minimum speed of around 45 mph right on up to the top speed of at least 175 mph,

it flew without a bad habit.

Its first time on a race course came, appropriately enough, at Cleveland, during

the 1971 Formula I races at Lakefront Airport. To get there. Steve hopped into his

flying Volkswagen and covered the 500 miles from Oshkosh in just three hours flying

time. His few laps were strictly an exhibition. but he showed a lot of people that

his low-powered sport plane could not only fly cross-country in fine style, but

also wrap itself around a tight pylon course like a true racer. Its first time on a race course came, appropriately enough, at Cleveland, during

the 1971 Formula I races at Lakefront Airport. To get there. Steve hopped into his

flying Volkswagen and covered the 500 miles from Oshkosh in just three hours flying

time. His few laps were strictly an exhibition. but he showed a lot of people that

his low-powered sport plane could not only fly cross-country in fine style, but

also wrap itself around a tight pylon course like a true racer.

By now. a second Formula Vee design had flown and was attracting a lot of attention.

Young John Monnett's Sonerai had a cantilever folding wing with a thicker airfoil,

but otherwise resembled Steve's Vee in general arrangement. Monnett was eager to

get the class going, and so immediately began selling plans with enthusiasm-and

considerable success. Wittman preferred to hold back until he was 100 percent satisfied

with the design, though a few pushy friends were able to badger him into releasing

some drawings so they could begin building their own.

The months dragged on, however, and still there

wasn't a sign of a race, mainly because there were just the two Formula Vee airplanes-and

what kind of a race can you have with two planes? Dozens were being built, but race

organizers want some kind of assurance that at least a half dozen will show up,

before they'll agree to put up prize money.

Lacking races for h is airplane, Wittman continued to do what he could to stimulate

interest in the new class by flying airshows and by showing the folks what his machine

will do-such as fly it across the Rocky Mountains to Reno in 1972 to see the Air

Races. In classic Wittman style, he simply climbed in and took off. While crossing

the highest mountains short of the Pacific Coast, he climbed as high as 16,000 ft.

and reported the airplane handled "just fine" up there.

Each time a few more thousand people see Steve Wittman and his neat little VW

racer perform, a couple more think seriously about building their own. He has now

sold several dozen sets of plans, while Monnett must have topped the 100 mark. By

the summer of 1974, a half dozen or more should be flying, and the first race in

the history of Formula Vee could be upon us.

In fact, the Great Miami Air Races, scheduled for January 18-20, 1974, has tentatively

included a Formula Vee in its program. It may come off, and then again it may not.

But each step brings Formula Vee closer to reality. And if the exact date of the

first race is far from certain, one thing can be counted on: Steve Wittman will

be the odds-on favorite to win that first race, wherever it is.

There's a very good reason for that "No.1" on the side of Witt's V.

Notice:

The AMA Plans Service offers a

full-size version of many of the plans show here at a very reasonable cost. They

will scale the plans any size for you. It is always best to buy printed plans because

my scanner versions often have distortions that can cause parts to fit poorly. Purchasing

plans also help to support the operation of the

Academy of Model Aeronautics - the #1

advocate for model aviation throughout the world. If the AMA no longer has this

plan on file, I will be glad to send you my higher resolution version.

Try my Scale Calculator for

Model Airplane Plans.

Posted July 31, 2024

(updated from original post

on 12/15/2014)

|