Table of Contents Table of Contents

The Boy Scouts of America has published Boys'

Life since January 1, 1911. I received it for a couple years in the late 1960s while in the

Scouts. I have begun buying copies on eBay to look for useful articles. As time permits, I will be glad

to scan articles for you. All copyrights (if any) are hereby acknowledged. Here are the

Boys' Life issues I have so far.

|

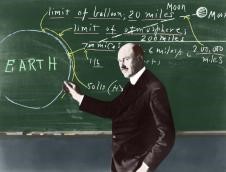

It was on March 16, 1926, that Robert

Goddard made history in Auburn, Massachusetts, by successfully launching the world's

first liquid fueled rocket. The propellant was a mixture of gasoline and liquid

oxygen. That was a mere ten year prior to this article that appeared in Boys'

Life magazine. Author T.E. Mussen comments that as of the writing, "thus far

the rocket has carried neither men nor recording instruments, nothing more than

the source of its own propelling power." Breathtaking speeds of 700 mph had

been attained and altitudes of 7,500 feet staggered the imagination with impossible

proposals - like someday sending human beings to the moon. The oft referenced

American Rocket

Society (ARS) was created in 1930, and was the leading professional group for

advancing rocket science. The group was planning for such missions three decades

before they became reality. ARS was merged with the Institute of Aerospace Sciences

in 1963 to become the present day American

Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA).

The Rocket Ship

By T. E. Mussen

The fastest man-made vehicle ever built is the

rocket. It has already achieved the speed of 700 miles per hour - 1000 feet per

second - or nearly the velocity of sound in air. But thus far the rocket has carried

neither men nor recording instruments, nothing more than the source of its own propelling

power. However, the possibilities of the rocket are not entirely fictional, startling

as they may seem. The fastest man-made vehicle ever built is the

rocket. It has already achieved the speed of 700 miles per hour - 1000 feet per

second - or nearly the velocity of sound in air. But thus far the rocket has carried

neither men nor recording instruments, nothing more than the source of its own propelling

power. However, the possibilities of the rocket are not entirely fictional, startling

as they may seem.

The experimental models now in use are aluminum tubes, seven feet long and four

inches in diameter by the American Rocket Society, twelve feet long and nine inches

in diameter by Professor Goddard in New Mexico.

The driving mechanism or motor, which is really nothing more than a firing chamber,

is at the head of the tube. Behind it are three chambers containing gasoline, liquid

oxygen and nitrogen respectively. Tubes lead from the gasoline and oxygen into the

firing chamber. The nitrogen is used simply to create pressure, and also because

it is itself an inert, non-reactive gas.

The gasoline is pushed by the nitrogen in a small, steady stream into the firing

chamber. The oxygen is pushed by its own pressure. Mixed, fired, they expand like

gasoline and air in an automobile cylinder. But instead of pushing a piston as in

the gasoline engine, the expanding gases in the rocket rush out through nozzles

like exhaust pipes.

The recoil from this release propels the rocket - the phenomenon belonging to

the class described in Newton's law that every action has its equal and opposite

reaction. The revolving nozzles of a lawn-watering apparatus are an example of this

law, the nozzles revolving in a direction opposite to the ejection of the water.

The recoil of a gun just fired is another example. The rocket can be thought of

as a gun stock moving backward through space, firing as it moves. In the rocket

the gas molecules can be conceived of as the bullets pushing toward the earth while

the rocket is pushed away, with nothing to stop it except decreasing air resistance.

The rocket operates twenty per cent more

efficiently in a vacuum. It needs no medium for traction. And its basic propelling

device requires no moving parts. Thus far it has been fired to altitudes of from

a few thousand to 7500 feet, but that has been done for recovery purposes, since

the results of each flight must be studied. And the Rocket Society has built its

rockets so that they float and has then fired them toward the sea, that they may

be more easily recovered. The rocket operates twenty per cent more

efficiently in a vacuum. It needs no medium for traction. And its basic propelling

device requires no moving parts. Thus far it has been fired to altitudes of from

a few thousand to 7500 feet, but that has been done for recovery purposes, since

the results of each flight must be studied. And the Rocket Society has built its

rockets so that they float and has then fired them toward the sea, that they may

be more easily recovered.

But the rocket's possibilities in covering great distances in a very short time

have been approximately calculated.

The theory, for instance, of a rocket flight from New York to Paris is that only

a brief part of the flight will be power driven, the rocket coasting after its initial

impulse. The rocket would be shot through the layer of dense atmosphere into the

high, rare altitudes. It would be aimed. It would still be travelling upward after

the initial charge was exhausted, later curving down toward its destination. The

path of its flight has been calculated like the trajectory of a shell.

The Rocket Society has estimated that the time of flight from New York to Paris

would be an hour and a half.

Light-sensitive cells would be used for accurate flight and landing. The rocket

would be aimed at a fixed star. The sensitive cells would be "tuned" to the light

from that particular star, much as a beam from Arcturus was used to open the Chicago

World's Fair. The cells could be connected to mechanisms in the rocket, switching

off nozzles on one side when the rocket veers, thus turning the rocket back to its

course.

By a time-clock device a new set of cells could be cut in when the rocket neared

the vicinity of Paris. These cells would be sensitive to a special light, such as

from a colored searchlight beam at the landing field. At a predetermined point they

would activate the release of a parachute, so that the rocket could float to earth.

The problems confronting a rocket flight to the moon, let us say, are far greater.

However, the flight has been contemplated and the American Rocket Society has in

its files the names of dozens of volunteers for such a flight.

In the first place, because, to effect such a flight, it would be necessary to

escape the field of the earth's gravitational attraction, a much greater initial

speed would be required. It has been calculated that that speed should be 25,000

miles per hour or seven miles per second. At that speed the rocket would be beyond

the force of the earth's attraction in about eight minutes. Thereafter, the original

aim and automatic navigation would guide it.

What seems most practicable is a step-rocket, that is, three or four rockets

hooked in series, firing consecutively. Three would be fired to reach the moon and

one to return. Getting back should be easier because of the lesser pull (because

lesser mass) of the moon, where an initial speed of only one mile per second would

be required.

Parachutes could not be used for landing on the moon, because there is no atmosphere

on the moon to support a parachute. It is thought, therefore, that reverse nozzles

would be used to check the speed - that is, nozzles exhausting the gas in the direction

of the rocket's motion.

But compounding rockets and mechanisms increases the load in a geometric ratio.

And with scientists, crew, food, instruments, oxygen aboard - 40,000 tons might

be the weight of such a rocket to the moon, such an "Astro-plane". That is as big

as the biggest battleship. And its cost would mount to thirty or forty million dollars.

So that a flight to the moon is at the moment very much an idle dream. But rockets

will be fired at the moon. And the first will no doubt be equipped with magnesium

flares that will go off automatically on landing. In that way we will know whether

we've hit the mark. And that will be a first step.

Posted August 3, 2022

(updated from original post

on 7/17/2014)

|