|

Website visitor Neil wrote to

request that I scan and publish this article for the Cessna Airmaster, by Patricia

T. Groves. It was scanned from my purchased copy of the May 1974 American Aircraft

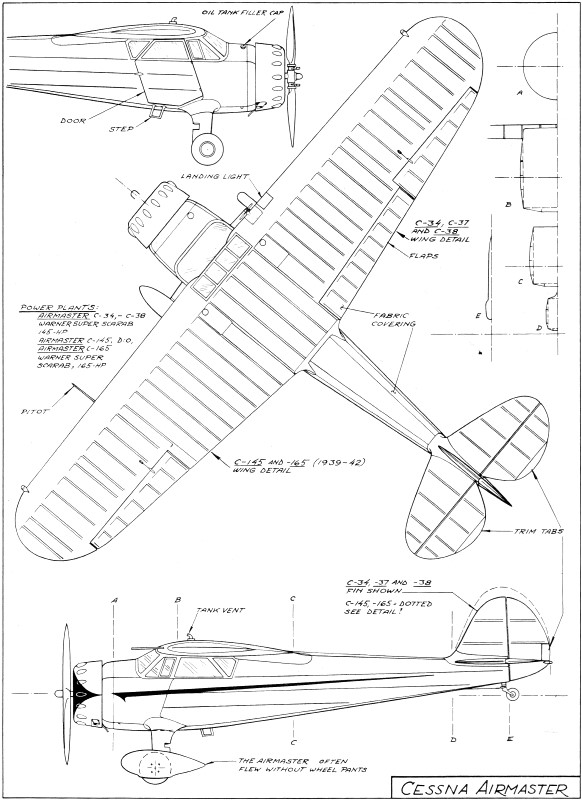

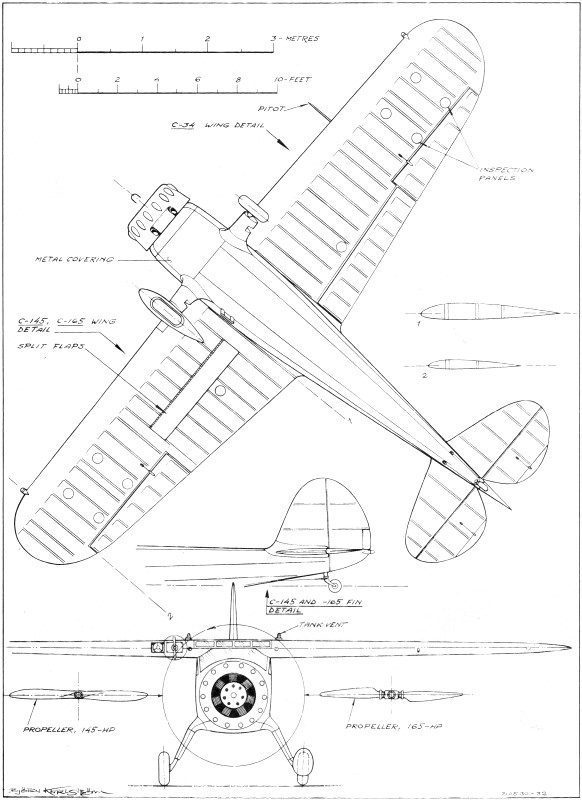

Modeler magazine (page 62). Line drawing for this fine aircraft were drawn by Björn

Karlström. All copyrights (if any) are hereby acknowledged.

Cessna's Past 'Masters

A tradition of excellence in lightplane engineering grew out of the Depression.

The mastermind behind it all was a guy named Clyde.

by Patricia T. Groves

June 1933 wasn't exactly a bright and shining year in which to be graduated with

an aeronautical engineering degree.

|

Entered in the 1935 and '36 National Air Races, C-34s brought home the Detroit

News Air Transport Trophy for aircraft efficiency both times. Winning these and

other airplane competitions led to the series name of Airmaster. (Photo courtesy

of The Smithsonian Institution)

On floats, on skis or on wheels, the C-37s enjoyed the highest production run.

From August 12, 1936, to May 13, 1938, 47 were built under ATC 622. (Photo courtesy

of The Smithsonian Institution)

No.4 in the C-145 series, this Airmaster (c/n 454) was completed on Halloween

1938. On virtually the same airframe as the prototype C-34, Cessna's continual upgrading

and refinement of the line was accomplished without sacrificing performance and

handling qualities. (Photo courtesy of Cessna Aircraft Company)

This C-165 (c/n 590) is one of the last in the Airmaster series. Basically the

same as the C-145, a 165 hp Warner Super Scarab gave the C-165s more, better and

greater all around performance. (Photo courtesy of Cessna Aircraft Company) |

Industry-wide, aviation was floundering, and many companies had gone Belly up.

Those managing to hang in there, were only doing so on a barely quivering shoestring.

Engineers, mechanics, pilots or constructors were happy to work - anywhere - even

if only to be able to say they were.

In June 1933, Dwane L. Wallace picked up his brand-new AeE (Aeronautical Engineer)

sheepskin and went out into the world anyway)

After all, when he'd started in at the university in Wichita, Kansas, things

sure looked promising enough. Aviation was a growing industry, and his uncle's Cessna

Aircraft Company was among the firms there in town. With 200 airplanes already off

its line, Cessna Aircraft was going great guns.

They were monoplanes, too, in a day when monoplanes were considered pretty freaky.

It was still a biplane era. And any monoplane with fully-cantilevered wings was

especially suspect. Like a prostitute-no visible means of support.

But Cessna monoplanes gradually gained acceptance within the aviation society.

During 1927, '28 and on into '29, good performance at air races earned good notices

and brought customers to the door. Americans like a winner.

And Cessna production aircraft were winning a good reputation as fast, efficient

airplanes. It all added up to a bright and shiny future. Then came October...

The shock waves of the Depression had an immediate effect. For many, the thin

line between extinction or survival quickly evaporated. Investor-held stocks became

pieces of paper, not even worth the pulp they were printed on.

But for Clyde Cessna, "extinction" wasn't an option. Deeply rooted in his nature

was an American Great Plains heritage, wherein wagon trains and a hard scrabble

history produced lean, diligent Westerners-fiercely independent and with confidence

in their own ability.

When Cessna stockholders gathered for their annual meeting in Wichita on February

5, 1930, a large black cloud enveloped the room. "OK," Clyde admitted, "so we're

in a bad situation. If we can't do what we planned to do, then we'll just have to

do what we can do."

Before anyone could argue, he pumped out a plan. "Look - some people still have

money and can afford to buy airplanes. And those that have airplanes are going to

need servicing. Furthermore, people want to fly. And if they can't fly airplanes-well,

we have this $398 glider that just about anybody can afford! It's salesmanship that

will beat this depression!"

Believing in himself, hard work and keeping the place open didn't exactly revitalize

the Board of Directors, but it did keep Cessna from collapsing. For the moment.

The Cessna Company managed to limp through 1930 selling gliders, an occasional'

airplane, doing maintenance work, renting out unused factory space, racing for (much

needed) prize money-anything to make a buck. But the massive debts just wouldn't

disappear.

Nor should determination and hard work erase stockholder pessimism. At the next

annual meeting, in January 1931, the Board of Directors threw in the towel. Although

not officially dissolved, the company nevertheless voted Itself into deep hibernation.

And Clyde was 'let out into the cold.

With his son Eldon, Clyde then opened up a small shop down the street and went

back to work. Getting through 1931, '32 and '33 under the name C.V. Cessna and Company,

father and son produced custom-built aircraft, including two racers.

These made-to-order airplanes were a progressive improvement over past Cessna

models. And, although not evident in the press of the moment, this period provided

an education for the future.

While the C.V. Cessna "School of Hard Knocks" was in session, Dwane Wallace Was

finishing at the university. He'd almost given it up a couple times himself, but

the family inability to quit-anything-was too strong. Then, in June 1933, he proudly

took his Bachelor's Degree to his uncle's shop in order to show him that he, too,

was ready to work.

They laughed and joked about how it all stemmed from the day, back in 1921 when

CV had crammed Dwane arid 'his two brothers, Dwight and Deane, into the front cockpit

of a Swallow biplane, and had taken them for their first airplane ride. And now,

Dwane was a pilot himself. And an engineer. And ready to work.

But a lot of water had gone under the bridge in those 12 intervening years. The

cold facts were that CV and Eldon were on short rations. They couldn't take him

on.

So Dwane Wallace talked himself into a job with Walt Beech, who had fired up again

in a rented area of the closed Cessna plant.

But, although Dwane went to work for Beech, he went to work on his uncle. Things

were beginning to open up now, and it was time for Cessna Aircraft to wake up and

get with it.

When the Board of Directors gathered on January 10, 1934, there was quite an

eye-opener ready for them. By .the time the meeting convened, a Cessna-Wallace windmill

was in full swing. At the end of that January day, there was almost a whole new

Board of Directors. Dwight Wallace, Dwane's attorney brother, had made a trip through

investor-land gathering up all the proxy votes he could muster.

With Clyde Cessna now President, Dwight as Secretary-Treasurer and Dwane in charge

of the plant, the new Board of Directors agreed to again manufacture the DC-6 line

of airplanes. Also, approval was given for the new airplane that was to become the

beginning of the Airmaster series of Cessna airplanes. From January 10, 1934,

until June I, 1935, when the prototype was completed, the C-34 (named for its design

year) was a successful combination of past Cessna Aircraft Company construction

techniques, Wichita University classes in aerodynamic theory and "School of Hard

Knocks" courses in what makes a winner.

Fabrication of the C-34, and subsequent models, was virtually the same throughout

the production life of the series. The welded steel fuselage was fabric-covered,

except for Dural in the area between the cockpit and the firewall, on the landing

gear fairings and the wing and fuselage fillets.

Using a NACA 2412 airfoil, the fabric-covered wings consisted of spruce ribs

and box spars. The chord of the wing tapered from 84 in. at the root to 56 in. at

the tip. Flaps and balance ailerons were mounted directly to the rear spar. The

C-34 marked Cessna's first use of wing flaps. Early ones were wood and fabric; later

models were metal.

Fabric-covered, cantilevered tail surfaces were of conventional wood construction,

while the rudder and elevator were of steel tube. A NACA cowl enclosed a 145 hp

Warner Super Scarab engine turning a Hartzell wood propeller.

The first C-34 (c/n 254) rolled off the line on June 1, 1935, and was flight-tested

by Cessna pilot George Hart. Flight trials revealed that the high-lift wing and

low drag construction gave the four-place airplane a cruise speed of 143 mph, a

maximum speed of 164 mph, and, with flaps activated, a comfortable landing speed

of 47 mph. Learning that your prototype achieves a better than one mile per hour

per horsepower makes for one of your more satisfying days!

These flights and the usual modifications and improvements that followed, soon

earned the C-34 the Civil Aeronautics Authority's No. 573 Approved Type Certificate-that

all-precious permit to go into production.

During this time there was precious little money coming in. As with all the airplane

manufacturing companies of the period, what cash there was on hand was used to stave

off creditors, so they wouldn't cut off vitally needed supplies and utilities. Workers,

only hired for the minimum required hours, had to be paid. This usually meant that

when paydays rolled around, company officers went home with a pocketful of Hope.

Hope in the future, hope that no one in the family got sick, hope that the land-lord,

the grocer, everyone could hold out-just a little longer.

While trials were still being conducted on the prototype C-34, the second (c/n

255) was sold. With a dandy $4985 destined for the company's emaciated treasury,

Dwane Wallace and George Hart decided to deliver the new airplane personally. Besides,

the trip would be a good cross-country test for the C-34. I n July, they flew c/n

255 from Wichita to its new owner in Tuxpan, Mexico, and averaged a most respectable

16.9 miles per gallon on the gas. With satisfaction over the results of the trip

adding more substance to all the hope everyone had been living on for so long, the

thing now was to get the word out.

After a Depression Years hiatus, the four-part Detroit News Trophy Race for aircraft

efficiency was again an event in the National Air Races, to be held August 3-September

2. Lured by the potential of cash prizes and much-needed publicity, Cessna's No.4

C-34 went to Cleveland. After copping the Detroit News Air Transport Trophy and

winning the 550 cu. in. displacement Sweepstakes, the C-34 returned to Wichita a

winner.

Production of the C-34 amounted to only nine that year, but the publicity that

resulted from the Cleveland Races brought customers to Cessna. By keeping Cessna

aircraft on the racing circuit and before the public, C-34 production rose to 33

in 1936.

On October 8, 1936, Clyde Cessna announced h is retirement, and Dwane Wallace

succeeded him into the presidency.

Improving and updating the C-34 led to the design of the C-37. By Christmas 1937,47

of these new models had rolled out the door. Wallace and Cessna employees could

now look back on the fallow years of 1931, '32 and '33.

Looking ahead to 1938, further refinement led to the appearance of the C-38 model

Cessna, and the first use of the Airmaster name. Based on past performance of the

series, they felt the C-38's new, curved landing gear, a larger vertical tail and

the addition of hydraulically operated fuselage flaps would solidify it with the

public. But something about it didn't sell-by September only 15 had left the plant-so,

back to the 01' drawing board ....

In September 1938, the prototype C-145 (so designated for its 145 hp Warner Super

Scarab engine) was completed. By eliminating the shortcomings of the C-38, the C-145

Airmaster incorporated further improvements of hydraulically operated brakes and

electrically operated split-type wing flaps. Here indeed was the master of the air.

During 1938, a gradual improvement in the U.S. economy, wider use of air transport

as a means of travel, expansion in air field and airport facilities, the growth

of air safety regulations and practices, all encouraged public acceptance of airplanes.

Sticking firmly to conservative policies, the company began to investigate the

twin-engine market, while continuing production of the successful C-145 and its

sister ship, the C-165 (165 hp Warner Super Scarab). Since both the prototype C-145

and C-165 airplanes are still on the active registry (as of October 1973), it would

appear that built-in obsolescence was not a Cessna practice.

From September 10, 1938, until events of December 7, 1941 closed down Airmaster

production, a total of 80 of the C-145s and C-165s were produced at the Wichita

plant.3 In .the C-165, a happy marriage of aircraft and engine design produced the

envious rating of one mph per each horsepower - not a bad figure after seven years

production.

References

1 Except as noted, all data furnished by Cessna Aircraft

Company.

2 Paul R. Matt, "The Airmasters from Cessna" Historical

Aviation Album (Vol. 4, Jan. 1969) pp. 14ff.

3 These figures include three C-165Ds (175 hp Warner Scarab

D engine) and one experimental General Motors powered GM Special.

Notice:

The AMA Plans Service offers a

full-size version of many of the plans show here at a very reasonable cost. They

will scale the plans any size for you. It is always best to buy printed plans because

my scanner versions often have distortions that can cause parts to fit poorly. Purchasing

plans also help to support the operation of the

Academy of Model Aeronautics - the #1

advocate for model aviation throughout the world. If the AMA no longer has this

plan on file, I will be glad to send you my higher resolution version.

Try my Scale Calculator for

Model Airplane Plans.

Björn Karlström Drawings:

Posted July 26, 2010

|