|

The 1946 Popular Science

magazine article discusses the development of tailless aircraft, focusing on the

American John K. Northrop's creation of the Army's XB-35 bomber. This innovative

plane, weighing 89,000 pounds empty, can lift 60 tons of bombs, gas, crew, and

cargo under overload conditions. Its boomerang-shaped wing is 4,000 square feet

in area, providing great lifting power and higher speed due to reduced parasite

drag. The XB-35 is expected to outfly the fastest conventional fighters and has

a theoretical range of 10,000 miles. Control is achieved through various

mechanisms like wing slots, rudders, and "elevons." The plane also enjoys

military advantages such as comprehensive fire power aft and the ability to

carry the atom bomb. Northrop's design overcame several engineering obstacles,

including the transition phase in take-off and landing, the tendency of tailless

planes to flat-spin, and the inability to glide to safety in case of engine

failure.

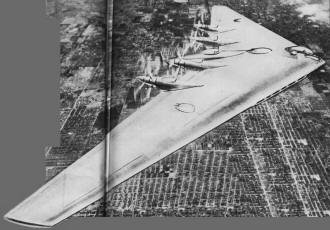

100-Ton Flying Wing

Artist's conception shows XB-35 in flight over Los Angeles.

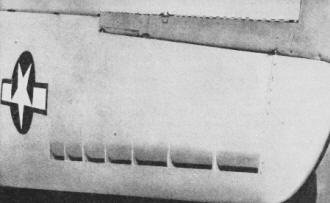

To the right you see open section of wing that may hold cargo. Outstrips B-29.

By Leon Shloss and Andrew R. Boone

Efforts to make tailless aircraft practical began the year before Orville Wright

was born. At least 40 pioneers, of nearly as many nationalities, have contributed

to the science. Now an American, John K. Northrop, has done it with the Army's XB-35

bomber.

This plane, weighing 89,000 pounds empty, under overload conditions will lift

60 tons of bombs, gas, crew and cargo. The 209,000-pound gross weight is 78,000

pounds more than that of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress. The boomerang-shaped wing

is 4,000 square feet in area, more than double the B-29's; hence the great lifting

power. Most parasite drag went out with the fuselage, and higher speed came in.

The speed figure is undisclosed, but it is known that the plane is expected to outfly

the fastest conventional fighters, which approach 500 m.p.h. Four Pratt & Whitney

3,000-hp. engines turn Hamilton Standard coaxial pusher propellers. Fifteen Flying

Wings have been ordered, with jet power in prospect for future models. The plane

will be shown about the time this story appears. First flight depends on progress

of pilots who are preparing to fly the radical giant. Complicating the problem was

the death of the outstanding Flying Wing test pilot, and the short, 5,700-foot runway

from which the first take-off must be made.

Under construction for three years, the XB-35 was designed so

that all external surfaces contribute to lifting it.

Wing slots on the N9M, 60-foot scale-model forerunner of the

XB-35, were added to increase stability at low flying speeds.

Control is achieved by slots, wing rudder and tabs, plus Northrop

"elevons," which function as combined ailerons and elevators.

This pseudo Flying Wing of 1929, with 30-ft., 6 -in. wing span,

contributed a lot of data to the plans of the XB·35.

Built by the Northrop Aircraft Co., at Inglewood, Calif., of a ware developed

aluminum alloy - 75-S - the XB-35 has a theoretical range of 10,000 miles - from

New Orleans to Singapore. Everything is carried within the wings including the engines,

excepting gun turrets and a pilot-canopy bubble. All external surfaces contribute

to lift. "Elevons" installed in the trailing wing edges combine the functions of

elevators and ailerons. Landing flaps, trim flaps and rudders are also in the trailing

edges. To move the controls the pilot uses a so-called "feel" system coupled to

a full hydraulic boost system. The "feel" applies varying pneumatic forces to the

control system at different speeds to hold control movements within safety limits.

The N9M was the last of four 60-foot scale models used to predetermine

the flight characteristics of the XB-35.

Further control is achieved by automatically operated long wing slots paralleling

the leading wing edge. These slots assure continued smooth laminar airflow at near-stalling

speeds.

Militarily, the XB-35 enjoys the unprecedented advantage of comprehensive fire

power aft, thus removing the airplane's greatest combat vulnerability - the hard-to-defend

tail. It also presents a smaller target-and can carry the atom bomb, a chore performed

heretofore only by the B-29.

Other advantages listed by Northrop will apply to cargo as well as fighting editions:

Low drag, high lift allowing transport of any weight faster, farther and cheaper;

simple construction; more even distribution of weight; spanwise compartments that

accommodate rectangular packing cases more neatly and can be loaded or unloaded

more quickly and easily than tubular holds.

Several foreign designers have built tailless airplanes that flew well, but they

encountered engineering obstacles, which Northrop presumably has whipped. There

is a transition phase in take-off and landing during which a tailless plane may

be hard to control. The biggest engineering hurdle, however, has been the tendency

of tailless planes to flat-spin, followed by inability to nose down in order to

recover. Until the wing was made thick enough to enclose engines, crew, payload

- everything, in fact - there was little aerodynamic justification for such a plane.

And a wing that thick meant a plane far larger than could be economically justified.

Military need in World War II for mammoth planes, and the current postwar demand

for volume and global air transport, brought about a wing large enough to increase

chord (depth of wing) to the point where the nose will go down.

Another shortcoming was the inability of tailless planes to glide to safety in

case of engine failure. This was ironed out along with the original problem when,

in the '30s, aircraft engines became so dependable that failures became virtually

unknown.

A great obstacle to Flying Wing development has been the timidity of industry

to delve into types untraditional and therefore hard to sell. It has usually been

the unconservative boss of the small shop who has waded into the lists of radical

design. That describes 50-year-old Jack Northrop, who has been designing radical

airplanes for 30 years. His first model of the Flying Wing, with a wing span of

30 feet, six inches, had twin booms and a tail, and so was not a true Flying Wing.

The first true Wing was flown in 1940, utilizing drooped wing-tip controllers, which

Northrop proved successful by experimentation with paper models. This plane was

built of wood, easily adaptable to changes in design. General H. H. Arnold, later

head of the Army Air Forces, saw this plane fly and ordered developmental work begun

on a huge Flying Wing bomber from which grew the XB-35.

|