|

At the time this "Dual Rotation-Reverse Thrust Propeller"

article

appeared in Flying Age magazine in 1945, the jet-engine-powered

aircraft were still mostly in the developmental stage, although both Axis and

Allied countries had managed to deploy a design or two at the tail end of World

War II. Commercial and military aircraft had been using variable pitch

propellers for a long time, even with reverse pitch for aerodynamic braking. The

concept of coaxial, counter-rotating propellers was a relatively new idea in

terms of building and testing working models for full-scale aircraft. Four

primary advantages of the configuration were more thrust for a given projected

propeller area, and the reduction or even total elimination of the

counter-torque associated with a normal propeller, the reduction or total

elimination of gyroscopic precession, and the reduction or total elimination

of p−factor (asymmetric

thrust produced by propeller blades presenting unequal angles of attack to the

relative wind). History shows that while the counter-rotating propeller has been

employed successfully in certain instances, it has not enjoyed widespread

acceptance - primarily due to cost and complexity.

Dual Rotation-Reverse Thrust Propeller

Curtiss dual-rotation prop, a twin, three-bladed. It will be used where diameters

are too large for single rotation efficiency.

Biggest news in props are these new developments, now being perfected and soon

to be more than high experiments.

The real "hot stuff" in propeller news is dual rotation. It was absolutely called

for. As engine horsepower and altitude ratings increased, the propeller had to go

right along. The early propellers, as we have seen, were two-bladed with narrow

blades. They were progressively superseded by three-bladed props with blades of

increasingly wider width and then by four-bladed propellers which in turn were forced

to employ wider and wider blades. To go beyond that point really efficiently, it

was necessary to consider dual rotation very very seriously.

The principle of dual, or counter, rotation is not new. The first recorded flight

of such an arrangement, but without controllable propellers, was that of Wolf Hirth

in February, 1912, near Berlin, in a Loutzkoy monoplane with two 100-hp. Argus engines,

each separately driving a tractor propeller. Its first modern successful use was

in the Italian Macchi-Castoldi twin-float racing seaplane which established a world

record of 440 m.p.h. in 1934. The multiple engines of this plane drove co-axial

counter-rotating shafts on which were mounted fixed-pitch propellers. And later,

in 1938, preliminary tests were conducted at Wright Field on a pursuit plane with

fixed-pitch dual-rotation propellers.

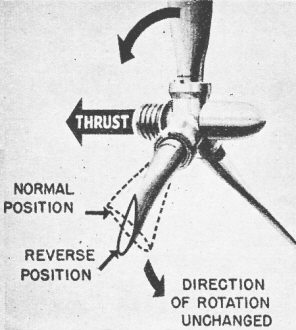

Sketch shows blade pitch change in reverse thrust. Braking is done by changing

the angle to negative pitch while rotating.

Today's dual-rotation props usually consist of two three-blade counter-rotating

propellers mounted in line on concentric propeller shafts. Its great advantages

stem, first, from the fact that the prop in back straightens the slip-stream. Secondly,

the balancing action of the two propellers mounted in line results in almost complete

cancellation of torque reaction. The result of all this is that vying span can be

reduced and so can the ailerons and other control surfaces.

(The torque reaction which is so important has been cancelled by other novel

devices. One of these is on the P-38, where one propeller rotates to the right and

the other to the left. And, incidentally, the greater problem of torque on helicopters

has been partially solved - notably in the small Hiller model - by using dual-rotation

rotors.)

The true application of dual-rotation propellers is primarily on the small, high-speed,

high altitude and highly-powered type of aircraft. Up to the present, however, the

arrangement has been tried primarily on installations where the four-blade, single-rotation

prop was nearly as efficient and of considerably less weight and complication.

To take one example, the Curtiss dual-rotation propeller is electrically actuated

and controlled to give constant speed or fixed-pitch control at all normal conditions

with provisions for full-feathering both propellers simultaneously. Both propellers

operate at the same r.p.m. in opposite directions. In line with present standards,

the outboard propeller rotates toward the right and the inboard propeller toward

the left, when viewed from the rear on a tractor installation. On pusher, installations,

the forward or inboard propeller has right-hand rotation and the rearward or outboard

propeller has left-hand rotation.

Against its important advantages, however, a special reduction gear in the engine

is necessary to provide the counter-rotation feature. That, of course, results in

a weight increase - but it seems to be a price worth paying when improved performance

is considered.

Second of the truly major and most recent propeller developments is that of "reverse

thrust" or aerodynamic braking. The term "reversing" means the operation of rotating

the propeller blades below their positive blade angle until a negative blade angle

is obtained in order to produce a thrust acting in the opposite direction to the

forward thrust normally furnished by the propeller.

What it means is that the airplane can back up. Actually, reverse thrust applies

only to the largest aircraft. Multi-engine flying boats which must land in restricted

areas, and large land transports, trying to reduce excessive landing runs need such

a mechanism. Propellers in reverse pitch have been used on large flying boats for

help in maneuvering on water for a number of years.

For satisfactory operation as a braking propeller, it is necessary that the

pitch range of the blades be substantially increased in order to permit propellers

to rotate to the negative angle of ten to fifteen degrees normally required. With

these angles the propeller will absorb the full rated engine horsepower at rated r.p.m, It is also necessary to have a higher rate of pitch change in going from

the operating angle to the reverse pitch angle than is desirable in the normal operating

pitch range where accurate engine speed control is required. This requirement of

a high rate of pitch change is similar to that used for feathering.

Aerodynamic braking by means of reverse thrust is a simple operation, really.

As the aircraft come in contact with the ground, the reversing circuit is energized

by a cockpit switch so that the propeller blades instantly rotate in the hub from

the positive into the negative blade angle. The direction of propeller rotation,

of course, remains unchanged. The aerodynamic forces produced by the revolving propeller

blades in their positive angle range to pull the airplane forward, now have the

opposite effect in the negative angle range and tend to push the airplane backward.

From a passenger's viewpoint, reverse-thrust braking is a significant development

in aviation. Its cushioning action eliminates any unpleasant wheel-braking effects,

thereby increasing comfort by a tidy bit. It has other ramifications, too, For,

with the adoption of reverse-pitch braking on airplanes, the landing run becomes

shorter than the distance required for take-off, making the take-off distance the

prime basis on which airport lengths will be determined. With the development in

the future of blind landing control, the added feature of reduced landing distances

through use of reverse-pitch propellers should play quite an exceedingly important

part.

Posted June 17, 2023

|