|

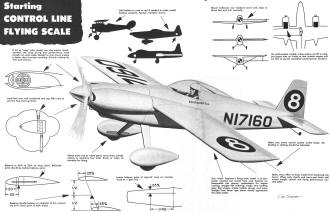

This "Starting Control Line Flying Scale"

article in the 1960 Annual Edition of Air Trails magazine is still

a good primer on how to go about getting into scale flying model

competition. Some of the contest rules have changed over the decades since,

but the basics are the same. The table of model sizes and engines might need

to be adjusted for electric powered models, but in the scale world there are

still many modelers who use internal combustion engines - especially in the

large airplanes. A quietly humming motor does not give quite the same

real-world affect as a screaming engine. Even with all the research going

into full-scale electric aircraft, we're still many moons away from have a

viable military fighter, transport, or commercial commuter. The drawing is

by the famous Cal Smith (as is the cover image), but the text of the article

is not attributed to any named author. BTW, this 1960 Annual edition has a

few other "Starting" themed articles on other realms of modeling.

Starting Control Line Flying Scale

If

kit or "mag" plan model, use size engine recommended. Use prop giving best performance,

even though not exact scale. Upright or side mount engine is better than inverted

mounting. Provide cooling air inlet and exhaust. If

kit or "mag" plan model, use size engine recommended. Use prop giving best performance,

even though not exact scale. Upright or side mount engine is better than inverted

mounting. Provide cooling air inlet and exhaust.

Lead fuel vent well overboard and cap filler tube to prevent fuel marring finish.

Balance at 20% to 25% of wing chord. Bellcrank pivot should be behind balance

point.

Biplanes should balance at midpoint of line connecting 25% chord point of both

wings.

Add ballast to nose or tail if needed to make model balance properly. Typical

examples shown.

Attach parts such as wheel pants, cover doors, bombs, rockets or auxiliary fuel

tanks firmly or make removable for flying.

Flying scale models have long been the top favorites in air-modeling. There are

more kits manufactured and sold and more magazine plans presented for scale models

than any other type. In competition, while other phases of flying such as free-flight

attract more contestants, everyone turns out to see the scale event.

Here is where more careful attention to craftsmanship and time consuming patience

is lavished than anywhere else. All too often the beginner attracted to flying scale

modeling is scared off by the sight of a beautiful model plowing up the macadam.

Sure, some crackups are inevitable, but many are preventable. Too often so much

attention is paid to the "scale" that the "flying" suffers.

Locate balance point of tapered wing on average chord at 1/4 span line.

So let's start at the prop and work our way back and discuss the most important

ingredients for successful flying scale modeling. First of all it must be remembered

that every scale model presents its own particular set of problems. There is no

really perfect scale model but control line flying minimizes most of the risks resulting

from a design that is not readily adaptable to scale flying. Some aircraft when

scaled down have wheels that are too small, tails too long or noses too short. but

the basic requirements of control line design must be incorporated into the model

or it will not fly correctly. Proper power for given size and weight model and proper

balance and trim make the difference between crack-up and good flying.

Choose a model of reasonable size to start with. Tiny Half-A (.049 cu. in. disp.)

powered scale jobs may be real cuties but are difficult to fly off anything rougher

than a ballroom floor. A ship with about 30" wingspan and a .19 engine is a good

workable size. Leave the 10' giants alone until you gain plenty of experience. If

you are building from a kit or mag plan the size engine will be specified. Use that

size! The designer has done the necessary test work for you already, so take his

advice.

Mount bellcrank and leadouts level and close to thrust line and C.G. vertically.

On multi-engine models unless engine cut-off

is used, put larger tank on inside so that outside engine will cut first to permit

controlled partial-power let-down. On multi-engine models unless engine cut-off

is used, put larger tank on inside so that outside engine will cut first to permit

controlled partial-power let-down.

This "ideal" beginner's flying scale model is no particular airplane but would

have such features as: Reasonable size spinner, apple cheeks for engine cowling,

straight flat midwing, single strut landing gear, big wheels, simple bubble canopy

and many straight lines. Racer type shown closely approaches the ideal model.

Make sure entire control system works freely. No binding or sticking should be

tolerated.

Make every effort to keep model from becoming too heavy. When scale details and

many-coat finish add excess weight, control and flying performance usually suffer.

Use the size prop recommended by engine manufacturer. This may not work out to

exact scale size, but appearance will suffer only slightly while power will not

be impaired. Avoid mounting engine inverted to prevent flooding, making starting

difficult. Use sidewinder and upright mounting whenever possible. Since engines

in scale jobs may be buried in a cowling be sure there is adequate space for cooling

air to get into and out of cowling to prevent over-heating. Provide plenty of room

for attaching booster clips to glow plugs. If you wish to cover over glow plug install

a small booster clip permanently on plug and lead wires out of cowling at some convenient

place.

Install the fuel tank as close to engine as possible and be sure fuel line is

free from kinks and sharp bends. Mount tank as in a stunt model if wedge type is

used, with center of tank level with needle valve. If a rectangular tank is used,

top should be level with needle valve. Extend overflow tube through bottom of model

so raw fuel will not mar finish. If possible provide a cap for filler tube so that

fuel won't slop out in flight. A short length of plastic tubing melted and squeezed

together at one end makes a simple cap. You may wish to use a balloon tank for your

scale model. Since this type tank has no overflow vents raw fuel won't spill on

model.

All too often the scale fan becomes so engrossed in crowding scale details onto

his pet that he ignores the basic requirements of balance, trim and control. These

factors cannot be ignored or that first flight may result in a beautiful wingover

with no pullout - splat! Don't hesitate to add a bit of lead ballast to nose or

tail to make model balance properly. C.G. should be located at 20% to 25% of wing

chord. On tapered wings locate this point on the average chord taken at 1/4 span

location on wing.

Biplanes should balance at mid-point of line connecting 25% chord point of both

wings. This applies to wings of equal chord. Unequal chord wings require a more

complicated method to locate C.G. correctly. But make such a model a bit on the

nose heavy side to be safe. The bellcrank pivot and line leads should be located

slightly behind the C.G. and lead outs can be angled back slightly to help keep

lines tight.

Another important factor concerning bellcrank location frequently overlooked

is its vertical location. Because scale models come in high, low and mid-wing types

a good rule to follow is: keep bellcrank and leadouts level and as near thrust line

and center of gravity as possible. Even if this means having leadouts exposed rather

than buried in wing. A typical example of incorrect location is in a cabin type

where lead-outs are run through wing. This suspends the model well above its Center

of Gravity point causing it to bank inward when under way and maybe to fly into

circle with loss of control.

The entire control system should be free from any binding or sticking because

stiff controls cause loss of control. Pay particular attention to leaving room for

elevator horn travel in buried installations. Lead out guides should be clear of

cement and dope.

Finding the right size wheels to fit any scale model may be tough. It is best

to use nearest size larger than scale so the mode) will roll well during takeoffs

and landings. Even smooth concrete may have expansion joints swelled by heat that

can trip up a model with small wheels.

To wear pants or not to wear pants? If your scale design has wheel pants they

should have adequate clearance inside around wheels. The pants should be attached

firmly so that they cannot be knocked off during rough landings. This requires a

knotty bit of building, but a little extra effort here will make a more durable

model. Other external details such as wheel cover doors, bombs, rockets and auxiliary

fuel tanks should be either "nailed on" tight or made removable for flying. A model

shedding parts in flight is an unnerving sight and can even cause a flyer to get

so excited he loses control of model.

Probably one of the greatest problems encountered with scale models is weight.

They just naturally seem to wind up being overweight. So make every effort to keep

weight of model within reasonable limits. Avoid hard wood and brass details, use

balsa and aluminum wherever possible. That contest winning finish can also be the

source of considerable excess weight.

Some builders use auto primer as undercoating for dope finish. Auto primer contains

lead and should be well sanded to lighten load. Use talc-dope filler for a good

lightweight undercoating. Cover planked areas with tissue rather than silk or nylon

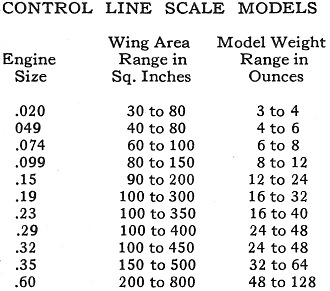

to help save weight. Since model weight and wing area govern the amount of power

needed to fly properly, the following table will serve as a guide to determine the

correct engine size. The table can only serve as a "rule of thumb" since individual

scale models vary greatly and exceptions may be necessary.

For multi-engine models: Select engine indicated by weight and range and divide

disp. by number of engines required. An example: A five foot span B-24 model weighs

Sibs. (80 oz.). This weight falls into the 48 to 128 oz. range, therefore .60 is

engine size indicated, .60 divided by 4 equals .15, or .60 divided by 2 equals .30.

The model can be flown with four .15's or two .29's. In actual practice this B-24

model (weight 72 oz.) was flown with two .19's because of propeller clearance problems.

With the recent upturn of interest in multi-engine models the flying scale modeler

has found his problems increase in direct proportion to the number of engines involved.

There are several factors that require particular attention to get a big B-25 or

B-17 flying successfully. Because it is practically impossible to tune all engines

to exactly the same RPM, a "beat" occurs that sets up some pretty unusual vibrations

throughout model. Engine mounts and nacelles must be extra strong and tied into

wing structure adequately or they will crack loose causing all kinds of ruddy ned

. Excess vibration may cause fuel flow problems because of foaming in tanks. Baffles

and shockproof mounting may be required .

Fuel tank size should be large enough so that when one engine is started it will

not drain its tank before the other engine is started. A helper standing by topping

off the tanks can solve this problem. Unless some sort of engine cut-off is used

it is a good idea to have inside engine tank larger than outside engine tank. Then

the outside engine will cut first and inside engine will keep the model pulling

on lines. On many multi-engine models an inside engine cutting first can cause disaster.

The best provision is for cut-off of all engines at the same time so that glide

to landing can be made rather than partial power let down. A third line or bellcrank-operated

fuel cut-off similar to that used on team racers does the job nicely.

Adequate propeller clearance on multi-engine models is always a problem. Frequently

it is necessary to use cut-down "clubs" to clear fuselage side or ground. These

are difficult to start and engines really scream causing unnecessary vibration.

If possible avoid cut down props and three or four-bladers since they are difficult

to balance and are real knuckle-busters. Fit the correct size prop to the engine

wherever practical (based on maker's say-so).

There are scale kits of every size and type available, no particular one can

be recommended in preference to any other, but to start with, pick a simple-engine

type. Lay in a large supply of patience and elbow grease and join the flying scale

fans. Great sport ... if you remember to thoroughly test fly your model before you

go to a contest!

Posted June 26, 2021

|