March 1967 Electronics World

[ Table of Contents] People old and young enjoy

waxing nostalgic about and learning some of the history of early electronics. Electronics World was published from May

1959 through December 1971.

As time permits, I will be glad to scan articles for you. All copyrights (if any) are hereby

acknowledged.

We

take for granted most of the technology that surrounds us. Unless

you were alive 50 years ago at the dawn of microelectronics and

space flight, it would be difficult to imagine a world without cellphones,

desktop computers, color TVs, the Internet, and even satellite-base

weather forecasting. Everyone likes to make jokes about weathermen

being no better at predicting the weather than your grandmother's

roomatiz[sic], but the fact is that, especially for short-term (2-3

days) predictions, we get pretty good information. As a model airplane

flyer, I check the wind level forecast nearly every day to see whether

my plane can handle it. AccuWeather's free hourly forecast is usually

pretty darn accurate for today's and tomorrow's wind - to within

a couple MPH. A plethora of ground reporting stations help improve

accuracy, but data streamed from spaceborne instruments are the

real key. This story in the 1967 Electronics World reports on some

of the earlier imaging weather satellites. Amusingly, it also predicts

the possibility of someday controlling world weather with the satellites'

assistance.See all the available Electronics World articles.

Weather Surveillance by Satellite

By Joseph H. Wujek, Jr.

Tiros, Nimbus, and successor ESSA satellites

are providing global weather information that may one day lead to

global weather control.

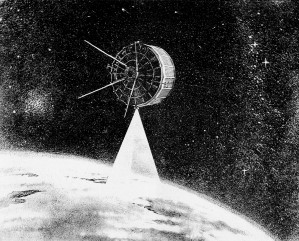

The new "cartwheel" Tiros photographs the earth as the satellite

rolls along like a wheel in a near-polar orbit.

To a great extent, man has learned to use the forces of nature beneficially.

A notable exception is our inability to control those forces in

nature which we know collectively as weather. Weather plays an important

part in social and economic well-being of a nation. Agricultural

output is strongly tied to the weather, as is the movement of ships

at sea, aircraft, and land transport. Indeed, commerce as a whole

depends to some degree on the behavior of the elements. In war as

in peace, a nation's fate may be decided by the perversities of

the weather. The defeat of the Spanish Armada, as well as the defeat

of Napoleon's armies on the plains of Russia, were due in large

measure to severe weather conditions. In view of all this,

it is not surprising that meteorologists continually searching for

new tools to aid them in understanding the weather. With increased

knowledge of weather comes the ability to predict the kind of weather

a region will experience. President Johnson, when Vice-President

and Chairman of the National Aeronautics and Space Council, estimated

the saving which our nation could realize if accurate weather predictions

were available only five days in advance. These yearly savings include:

$2.5 billion in agriculture; $45 million in the lumber industry;

$100 million in surface transportation; $75 million in retail marketing;

and $4 billion in water resources management. Beyond these dollar

savings, we have the priceless savings in human life which result

when hurricanes, tidal waves, and the like are detected in advance.

Clearly, then, research into the nature of weather will have a profound

effect upon our welfare. Until early 1960, meteorologists

were somewhat earth-bound in their measurements of weather phenomena.

True, aircraft and weather balloons were launched to measure wind

speed, barometric pressure, and other weather variables. Later,

sounding rockets were also used to obtain these measurements. But

these measurements are somewhat localized in that only a small region

of the atmosphere or stratosphere is sampled. And, as we know, weather

is by no means predictable by immediate local conditions. A storm

front in the far reaches of Canada's Hudson Bay on Tuesday can create

havoc with cattle ranches in North Dakota on Thursday. Even with

many remote weather stations positioned at strategic points around

the world, severe weather conditions can be building up while unobserved

by these stations. A system for weather surveillance which could

survey large sectors of the earth was urgently needed.

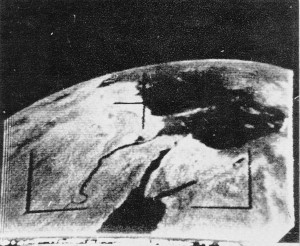

This view of the Nile River and its Delta, the Red Sea, and

the eastern Mediterranean was taken by Tiros III from an altitude

of 400 miles.

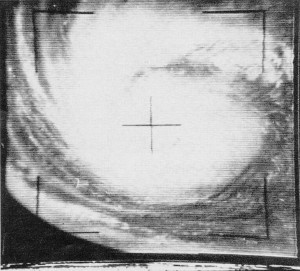

The vortex of the Hurricane Daisy photographed several year

ago off the east coast of the United States by the Tiros V satellite.

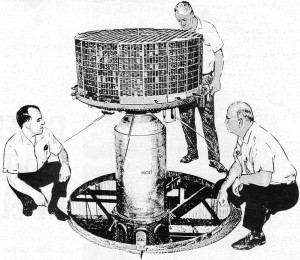

The Tiros VII being checked out prior to its launch into space.

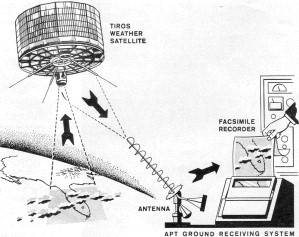

The APT ground receiving system uses fairly simple, inexpensive

ground-based equipment which employs conventional facsimile

recorder.

The Tiros Satellite System The Tiros (Television

Infra-Red Observation Satellite) series provides a partial solution

to this requirement. These vehicles, equipped with television cameras

and infrared (IR) radiometers, gather data for analysis by meteorologists

within hours after the observation. The first in the series, Tiros

I, was launched from Cape Kennedy on April 1, 1960. At this writing,

ten Tiros satellites have been launched.

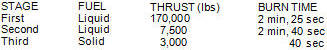

Table 1. Specs for Thor-Delta booster which launched Tiros.

The Tiros is an 18-sided vehicle, 22 inches high by

42 inches in diameter, weighing about 300 pounds. Each of the 18

faces of the satellite is an array of solar cells. These 900 solar

cells furnish charging current for the 63 nickel-cadmium cells which

furnish power throughout orbit. Two 18·inch receiving antennas extend

from the top of the satellite and are used to receive ground commands.

Four 22-inch telemetry transmitting antennas are located on the

underside of the package. Tiros I through VIII had two vidicon TV

cameras mounted on the underside of the satellite. Later Tiros spacecraft

have side-looking TV cameras mounted on opposite sides.

The Tiros series is put into orbit by the three-stage Thor-Delta

launch vehicle. Table 1 gives important specifications for this

space booster. For some perspective, recognize that jet engines

used on modern commercial airliners have typical ratings of 16,000

pounds thrust per engine. Hence, the first stage alone of the launch

vehicle delivers more thrust than ten of these aircraft engines.

Launch vehicles have since been developed which generate more than

two million. pounds of thrust. Tiros orbits range from 450

miles to 860 miles, with periods (time for one revolution) of 90

minutes to 113 minutes, respectively. At the 450-mile orbit a region

on earth of 800 to 1000 miles in diameter is covered by one transmitted

TV picture. Tiros I through VIII were placed in a general

east-west orbit, resulting in coverage of about 25% of the earth's

surface. Later Tiros launches resulted in a north-south, or polar

orbit. The polar orbit permits coverage of nearly all the earth's

surface. The polar orbit is also selected so as to be nearly synchronous

with the sun. The sun-sync orbit results in backlighting from the

sun during the northward pass of the satellite, producing high-quality

photographs. Tiros I-VII made use of a focal-plane shutter

in conjunction with the two vidicon TV cameras. Pictures are stored

on the tube face and converted to data bits for storage on magnetic

tape or direct readout by ground stations. Each orbit results in

64 pictures, or 32 pictures per tape. Transmission of data to the

ground station requires about three minutes. The data transmission

simultaneously erases the magnetic tapes for the next data-gathering

pass. The operation of the readout system as well as the timing

of the picture-taking sequence is accomplished by ground command.

The ground command sets timers which activate the camera system

when the satellite passes over the region of interest. Starting

with Tiros VIII, a new system of data readout was used. The new

system is designated Automatic Picture Transmission (APT). Rather

than construct a TV picture line by line, electronically photograph

the screen, and then store or transmit, APT uses a system similar

to that used by newspapers and the press services to transmit photos.

A facsimile recorder then reproduces the picture as received.

Ground receiving stations for Tiros are Wallops Island, Virginia;

San Nicolas, California; and Fairbanks, Alaska. Over-all direction

of the Tiros system stems from Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt,

Maryland. These stations are capable of receiving data when the

satellite draws to within 1500 miles of the station. The received

pictures are photographed by 35-mm camera for immediate analysis

by meteorologists. In particular, these photos reveal conditions

of cloud cover as well as the presence of hurricane conditions.

In addition to the TV camera, infrared radiometers measure

the amount of reflected and absorbed solar IR energy. The amount

of IR energy absorbed and reflected determines the heat balance

of the earth and therefore affects the weather. The IR data is transmitted

and received as non-photographic data. This data is later reduced

and plotted on weather maps for analysis. While the IR data is not

immediately useful to meteorologists, it nevertheless provides a

kind of long-range weather behavior of our planet.

The initial design of Tiros called for a mission life of three to

four months. The first Tiros was operational for 2 1/2 months. Later

Tiros vehicles operated for well over one year. In the first three

years of operation some 300,000 TV photographs were transmitted.

Tiros I completed 1302 orbits and relayed 22,592 pictures to ground

stations. As seen in the accompanying photographs, Tiros

has produced some startling results. Of particular importance were

other photos taken by Tiros III in Sept. 1961. These photos revealed

the build-up of Hurricane Carla. As a result of this early warning,

approximately 350,000 persons withdrew from the storm region involved

and injuries and loss of life were held to an absolute minimum.

Second-Generation Satellites In

addition to the ten Tiros launchings, two each ESSA (Environmental

Survey Satellite) and the Nimbus satellites that have been orbited.

The ESSA satellites are similar to the earlier Tiros systems

and operate in the "cartwheel" mode. ESSA I was launched on February

3, 1966 and carried two half-inch vidicon TV cameras into a circular

460-mile-high polar orbit, having a period of about 100 minutes.

ESSA II carried two APT cameras into a circular 860-mile-high polar

orbit with a 113-minute period. NASA plans to keep two ESSA satellites

in orbit at all times. As one ESSA vehicle ceases to transmit, a

replacement will be launched. The ESSA satellites represent the

operational system for which the Tiros vehicles were the research

and development packages. The Nimbus represents a

more sophisticated weather satellite system. In particular, Nimbus

is not restricted to photographing the earth during daylight. By

means of its high-resolution red radiometer (HRIR) system, night

photos are obtained. These photos appears as dark or light regions,

depending on whether more or less heat is radiated, respectively.

In addition to the HRIR system, three vidicon cameras

are used. From an orbit of 575 miles, resolution of one-half mile

is possible. The APT system was also flown on the Nimbus.

Nimbus I was moderately successful after launch on August 28,

1964. The second stage of the launch vehicle did not burn as long

as required, resulting in an elliptical orbit of 252 miles perigee

and 578 miles apogee, rather than the planned circular 575-mile

orbit. The satellite transmitted many useful photos until a solar

panel locked and was thus unable to track the sun. As a result,

Nimbus I ceased on September 23, 1964. Nimbus II was successfully

launched May 15, 1966, carrying HRIR, APT, and vidicon systems.

NASA plans to launch a Nimbus satellite approximately every 18 months.

These vehicles will serve to test new systems for improved weather

observations . The Tiros vehicles and successors form the

Tiros Operational System (TOS), which is a joint undertaking of

the U.S. Weather Bureau and NASA. In addition to the benefits already

listed, the Tiros system may provide scientists with new insight

into such phenomena as clear-air turbu-lence (CAT) and the nature

of the "jet-stream." Perhaps history will someday

show that Tiros provided a significant advance toward a goal we

have desired, control of the weather. A system of sophisticated

Tiros-like satellites, relaying weather data to a central computer

which directs corrective (and as yet unknown) action to smooth the

weather, is presently but a dream. But the translation from dream

to design to hardware has been foreshortened considerably as our

technology advances.

Posted May 27, 2012

|